Birmingham’s Blight – Ravaged Inner City Communities Ready for Change

Birmingham has received national attention for its booming downtown revitalization and new development projects. But that’s not the whole story. Less than a mile from downtown gems like Railroad Park and Regions Field, inner city neighborhoods struggle with decaying, abandoned homes and overgrown vacant lots. Birmingham’s most recent budget devotes $6.5 million to tackling these problems.

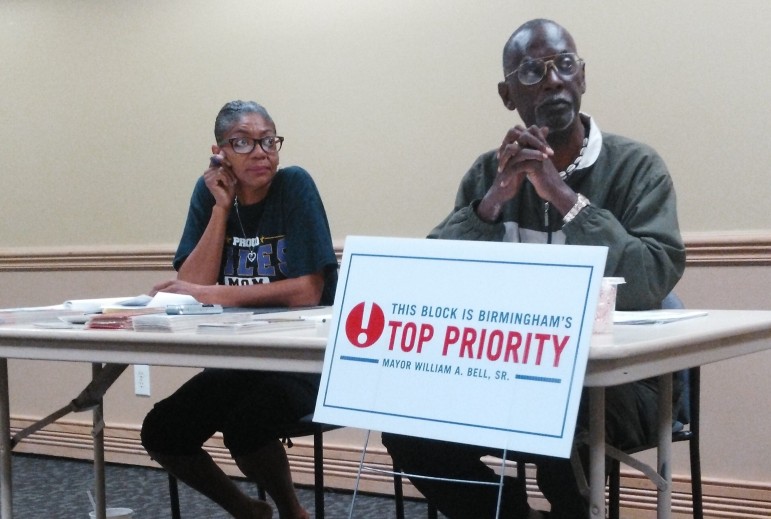

The View From North Titusville

North Titusville, A small group gathers for a neighborhood meeting in North Titusville. From the front of the room President John C. Harris stands tall. He holds up a white yard sign and announces to the audience, “If you see this sign on your block, it it to let you know that your block is a priority,” says Harris.

Harris is talking about city’s plan to eliminate blight, something everyone in his community wants to know more about. In North Titusville, almost every street is littered with burned out and empty homes. Harris has lived in the area his whole life. He has watched many residents give up on the neighborhood and leave. “I chose to stay here and I’ve been fighting a battle, you know, for years,” he says.

Harris keeps meticulous record of vacant homes and empty lots in North Titusville, and regularly lobbies the Birmingham City Council to bring attention to the problem. He says these empty buildings are an eyesore, and they attract crime to the area.

“We’d rather see a vacant lot than to see a house sit here where you got drug activities, prostitution,” Harris says. “In that house police found a guy that had been there two days with a needle in his arm.”

The Extent of the Problem

The city is finally taking notice. John Colón is the director of the Department of Community Development. He says change starts with the city getting rid of abandoned structures. According Colón, Birmingham currently has over 16,000 deserted, tax-delinquent properties. Colón says the sheer magnitude of the problem is unique. “I think it’s important to note that we’re attempting to do in Birmingham is unlike anything that’s been done in the country,” he says. “And possible has never been a part of the discussion; we’re saying we don’t have a choice, our city is under siege right now.”

Birmingham Mayor William Bell agrees. He adds that up until recently, the city’s options were limited.

“We could condemn it and go in and tear the house down. But we couldn’t do anything else with the property,” Bell explains. “The problem with doing those things is that it would be a recurring cost to the city if we have not come up with a plan long-term to deal with it.”

A Plan for Action

Mayor Bell launched the RISE (Removing Blight, Increasing Property Values, Strengthen Neighborhoods, and Empowering Residents) initiative in 2013. A main component is the Land Bank Authority. Land banking programs are used throughout the country, helping cities like Detroit, Chicago, and Seattle tackle years of blight. Birmingham received the ability to create a land bank in 2013; the city council approved the initiative in 2014, and Bell says the program is now kicking into high gear.

Bell explains how the initiative works. “We can take that property or that house if it has not had the property tax paid on it in a 5 year period of time, gain control over that property and then put it back to a productive use,” he says.

Essentially, the Land Bank Authority clears up property titles, so they can be transferred to someone else. A central aspect is the Side Lot Program, which allows residents to purchase neighboring lots at a low cost. Heager Hill is the Chairman of the Authority. He says the group’s current mission is to raise awareness in the community. “Right now we are more intent on trying to get homeowners and people interested in buying the properties, and the side lots,” he says.

Hill says residents have complained about blight for years. The Land Bank Authority finally offers a solution. “We are happy that we have this program, and we are gonna do all we can to move it forward with the help of the city,” Hill adds.

Hoping for Change

In North Titusville, John Harris says he is ready. From his records, there are more than 300 abandoned properties in his neighborhood alone. Last year, the city agreed to demolish 19 of them. Bringing the neighborhood meeting to a close, he remains optimistic, claiming, “10 years from now, everything goes as it should, you will see a new and different Titusville.”

He says that, despite the fact that most of those 19 vacant homes are still standing. But Harris thinks the city means it this time, and hopes 2016 will be the year he finally sees change.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.

Week in Politics: Does Trump have political support for his actions in Iran?

We look at what President Trump's decision to attack Iran means, what kind of support he has in Iran and what this moment means for his administration.

Unlocking the secrets of an ancient plague

The first historically recorded pandemic is believed to have struck the walled city of Jirash, in what is now modern-day Jordan, in the 7th century. A new study reveals details about those who died.