Birmingham Revitalization: The View from a City School

A little background:

Almost four years ago I went to Avondale Elementary to report on a group of white, middle-class parents who’d decided to send their kids to the school where they lived. In many places, that wouldn’t be unusual. But in Birmingham, it was, and is. The school system is 92 percent black, 65 percent on free lunch, and especially back then, it didn’t have the greatest reputation. But Avondale parents – black and white, then and now – see beyond that.

“It’s just exciting to see different people come in, wanting to help, wanting to be a part of Avondale Elementary School,” says parent and volunteer Valencia King.

PTA president Alison Jenkins agrees. “I think it’s beautiful that Avondale is more representative of entire Birmingham now. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Although Avondale the neighborhood began booming and diversifying long before the school felt a ripple of middle-class influx, principal Courtney Nelson sees those changes affecting the school now.

“We’re getting to know more about different cultures and different lifestyles, and we’re embracing those,” she says. “We’re learning to live positively in a heterogeneous community. That’s real life, and that’s what we’re bringing to the kids here … And we have a lot of believers in the business community now, too.”

All of this comes with very real ramifications. Other parents say the main reason they came to Avondale was its diversity, and a wide body of research shows benefits for kids in racially and economically diverse schools.

According to Dr. Anthony Hood of UAB’s Collat School of Business, “When you have this economic revitalization where you have middle-class families moving into a formerly depressed neighborhood, those people bring – into that neighborhood and into those schools – access to information, resources, and connections to influential people. And so what happens is, the scores overall of the school tend to go up.”

But even putting aside the limits of test scores as measures of education quality, he worries that test score increases for an entire school don’t necessarily mean its poor kids are doing better.

“Are the indigenous people – those students who were already there, who are from those disadvantaged backgrounds – are they better off because these people with greater means have moved into the school system? It can be very tricky when you’re just kind of looking at overall scores.”

(Speaking of tricky, discerning real trends in Avondale’s test scores is basically impossible, given recent changes in standards, grade-level expectations, and the tests themselves.)

Hood also points out that you can have segregation within diverse schools through talented-and-gifted programs or when wealthier parents – who often have more resources, connections, and time – exert more “pull” in the school, PTA, or community, resulting in moves that, intended or not, help their kids more than those of others. And he has other concerns.

“I think the fear that a lot of people have is displacement,” Hood says. “If a school is 90 percent African-American, or 90 percent people of color, and now it starts becoming increasingly more white – white and middle class – then what happens when it hits that tipping point to where now you have mass displacement of the people of color who are already there?”

Even some very middle-class parents, black and white, say they fear being “priced out” of Avondale. It bears mentioning that the neighborhood is seeing a revitalization most chambers of commerce, tax collectors, and realtors can only dream of.

There are neighborhoods and school zones in Birmingham where the issue of being priced out might seem like a good – or at least better – problem to have. As Hood puts it, “we need more efforts to make sure that we are creating demand mechanisms for all of our neighborhoods, not just those on the east side of town and Downtown and Southside, but also Ensley and Norwood and North Birmingham and Titusville, to make sure we are creating reasons for companies as well as people to come and invest in those areas.”

Though in Avondale the area changed first, those demand mechanisms could include schools. It’s a chicken-and-egg thing. Hood’s research assistant, Americorp member and small business owner Ariel Smith, says schools are the hubs of communities, so “when schools are building, when neighborhoods are building, it’s going to attract homeowners to that area. It’s a great opportunity for us to come together and to figure out, okay, ‘how do we move forward for the betterment of everyone in that school.’”

Extending that goal to the whole city, Anthony Hood puts things plainly:

“I think if you had both white middle class and black middle class choosing to be in the inner city, but also doing it in a very conscientious fashion as to not to displace those who are already here, who have been here for decades, I think we can achieve a much more equitable and diverse Birmingham.”

Avondale has been booming for a while, and Avondale Elementary – now 10 percent white, diverse by Birmingham standards – is slowly becoming more diverse. The school seems to be both reflecting and causing neighborhood changes. But it’s complicated, and whether it works for everyone depends on people seeing past their own benefit.

WBHM intern Joseph Bodkin contributed to this report.

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

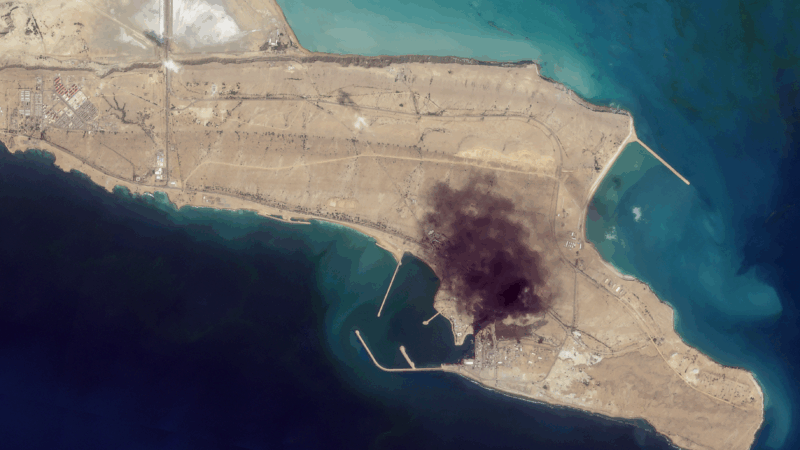

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

Sunday Puzzle: Sandwiched

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WXXI listener Jonathan Black and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.