Birmingham Revitalization: Some Neighborhoods Feel Ignored by City Hall

When David VanWilliams moved to Birmingham, he was looking for a fixer-upper and fell in love with the neighborhood of Inglenook. Inglenook sits just north of the airport. Like its southern neighbors, Crestwood and Avondale, Inglenook has turn-of-the-century brick bungalows and wide streets with sidewalks. But unlike those other neighborhoods, potholes mark the roads and many houses are in disrepair. Residents don’t have the money to fix them.

“Actually, I would just could say that there is a divide between South Birmingham and the rest of Birmingham,” VanWilliams explains.

VanWilliams says that many of his neighbors lived here during and the Civil Rights Movement, but they haven’t seen much progress in the fifty years since.

VanWilliams is a carpenter, so about two years ago, he decided to try to fix two of the neighborhood’s biggest problems: crime and derelict homes. In an effort to get young people off the street, he would teach them carpentry, and together they would take on neighborhood projects at a big discount. Two birds, one stone.

“Watch your step,” VanWilliams cautions, as he steps into a two-room addition he’s building onto the home of Henry Elmore, a neighbor and former baseball player with the Birmingham Black Barons. Elmore can’t afford to pay much for the addition, so VanWilliams and the students work cheaply.

So far, VanWilliams says he hasn’t been able to get the city leaders to recognize the needs of his neighborhood.

“Rather than ignoring the frustrations of the people, we feel like city money should be spent to improve the conditions of the people, instead of us writing [the problems] off as normal,” VanWilliams says.

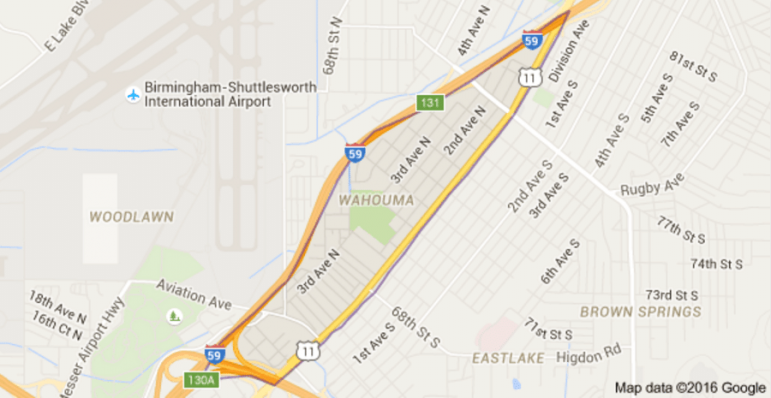

On the other side of the airport is the neighborhood of Wahouma, a narrow sliver of a streets sandwiched between 1st Ave North and Interstate 59.

“I am going to take you where a whole neighborhood is empty,” say Pat Johnson, Wahouma’s neighborhood president. “Keep straight. I am going to show you Abandonsville.”

Johnson has lived in Wahouma for about 30 years, and she regularly drives through the neighborhood noting abandoned homes, blocked sewer drains and piled-up trash.

Along the flat, sunny street are crumbling, clapboard houses with sunken in roofs. Many are doorless with smashed windows. Some are half burned. Others are swallowed in kudzu and overgrown shrubs.

“That’s empty, that’s empty, that’s empty,” Johnson counts down the houses on both sides of one street. She lets out a short, frustrated laugh.

In her unofficial count, Johnson says these few streets have more than two dozen abandoned homes. Johnson says she has written to the city, but nothing seems to get done.

Neighborhoods like Wahouma and Inglenook are old. Built in the 1920s and 1930s, they were solid, working-class communities, until the city started to empty out following the civil rights protests of the 1960s. In the fifty years since, Birmingham has lost more than 100,000 residents, and Johnson complains neighborhood like hers were left to suffer with blight, crime, and increasing poverty.

Johnson says she wants to see new people and businesses moving into Birmingham, but she also wants to make sure that her neighborhood isn’t passed over.

“While that is happening downtown, people in communities that have been neglected for 20 and 30 years they are not getting any piece of the pie,” Johnson explains. “They are not getting the crumbs.”

Mayor William Bell says that the city’s neighborhoods are getting more than just crumbs.

“What I would suggest to anyone that listens to this program,” Bell says, “is that they get into their car, and ride out to North Birmingham.”

Bell points to parks that have been redone with new swimming pools. The city built a new library in Prattville and remodeled one in Inglenook, and constructed new pedestrians bridges to help residents cross intersections and railroad tracks.

“What you have to understand is that with 50 years of out migration, 50 years of neglect, you can’t turn that ship around overnight,” Bell explains.

He says that he wants to encourage development and investment in all of Birmingham’s neighborhoods — but that to attract developers, neighborhoods also have to bring some resources to the table. Bell acknowledges that many neighborhoods, likely the majority of neighborhoods, are impoverished.

“Those are the places that we have to spend money to put in the public infrastructure to make it attractive to someone to come out and invest,” Bell explains.

That’s exactly what Johnson and Van Williams say they are asking for – small projects – like helping residents get cans of paint to touch up their homes or enforcing city ordinances about trash and noise. Little things, they both say, would go a long way to making their neighborhoods feel a part of the city.

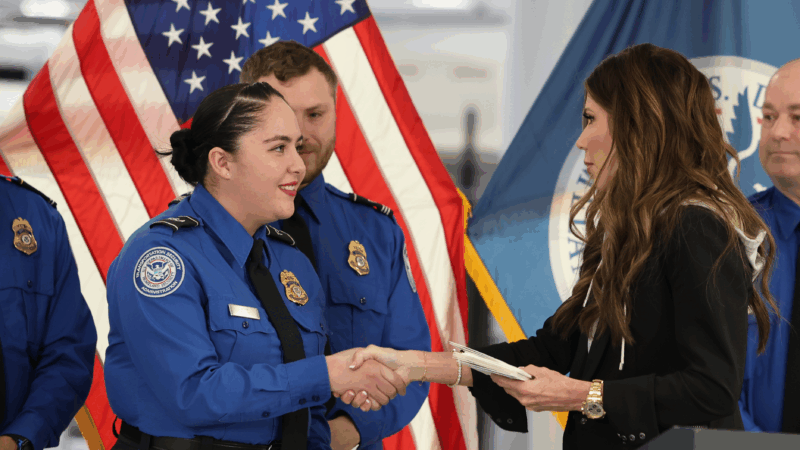

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

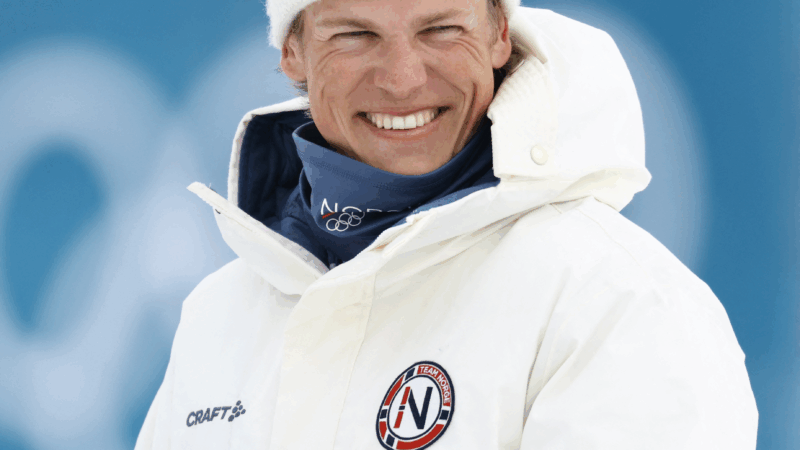

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.