Pushing Middle-Schoolers All The Way Through College

Fewer reading materials in the home. Less access to camps or museums. Those are some reasons summer learning loss disproportionately affects low-income kids. And there are many in the South, which can hamper efforts to raise graduation rates. But in the second part of this Southern Education Desk series, WBHM’s Dan Carsen reports on “GEAR UP Alabama” — a wide-ranging federally funded attempt to meet those challenges, and more. Listen above or read below.

A surprisingly good student band is doing its thing on the last day of a weeklong music camp at Alabama’s picturesque University of Montevallo. The camp attracts talented kids from around the Southeast, mostly from families who can afford the tuition. But through a grant program just getting started, students who otherwise couldn’t are joining in.

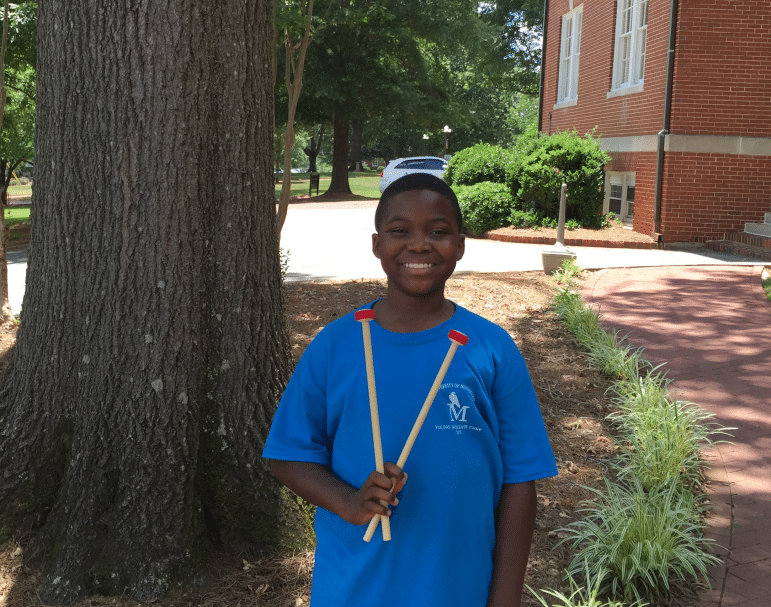

Middle-school drummer Ashton Bridges was nervous about staying more than a hundred miles from his Phenix City home for the first time. But it’s all good now.

“It’s been cool,” he says. “We’ve been learning new music and playing new instruments, like timpani, and mallet xylophone, marimba. Some of it I’d never seen before.”

Being around different kinds of people was also new for Ashton.

“It’s scary at first, but you get used to it. They were funny and fun and they were nice, and I made new friends.”

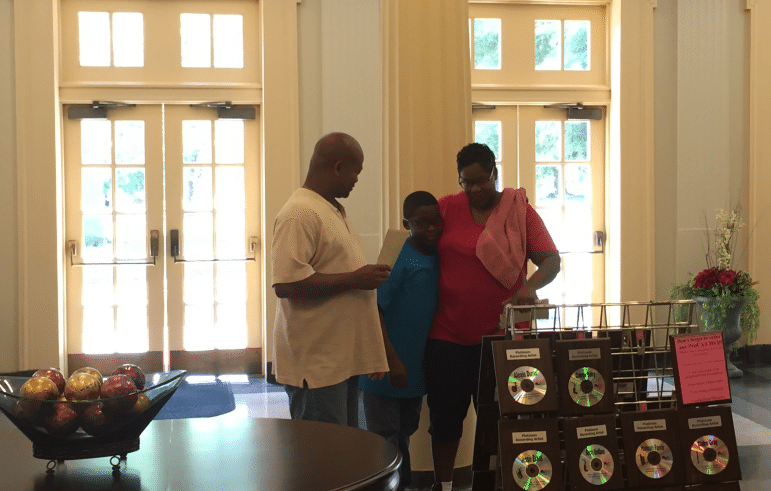

Ashton’s mom Barbara Bridges is thankful he had the opportunity. “Without the GEAR UP program, it probably wouldn’t have been possible,” she says.

Ashton and four other students from Alabama’s low-income Black Belt region got camp scholarships through GEAR UP Alabama, one of ten of these statewide grants announced by the U.S. Department of Education last fall.

Program Director James Davis says the approach is unique because “it begins with the seventh-grade cohort, and it follows them through the educational pipeline,” meaning through high school and potentially beyond. The six- or seven-year, locally matched grants are meant to help low-income kids get to and through college or trade school. That means boosting ability and aspiration. So besides tutoring, scholarships, financial aid workshops, and other GEAR UP staples, another tactic is to expose kids from isolated areas to new institutions and to new people. Barbara Bridges says that part was hard for Ashton, partly because he was homesick, at least at first.

“It was an experience,” she says. “And his roommate had been here before, and he was very encouraging. That helped us, a lot.”

There’s a separate GEAR UP program in Birmingham City Schools, but the $3.5-million-a-year statewide grant is meant to help more than 9,000 kids from the poorest and most isolated counties across Alabama, which are some of the poorest and most isolated counties in the United States. But staffers are trying to punch through that.

“There’s life, outside of, you know, our stop sign,” says Samantha Elliot-Briggs, one of six GEAR UP Alabama regional coordinators. “So many children who are just 30 miles down the road may not have resources or transportation to come to the University of Alabama and see its campus.”

But, she says, you can plant seeds. “To be able to travel from their small towns to a university campus and to have that experience and that exposure, spend the night away from home.”

GEAR UP stands for Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs. So anything that puts college on the radar, gets kids into challenging courses, or supports them through and beyond high school is fair game. Social skills are key, too, and not just for the workplace. GEAR UP Alabama director Veronique Zimmerman-Brown used to teach at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, which is overseeing the grant. She says, “They’re not getting along in college either! They’re having to break up disagreements in the dorms. I mean, little cat fights in the cafeteria. And you’re in college.”

And she’s not blaming students or their families. She adds, “rather than complaining about it — ‘Oh it should come from the home!’ — well, you’re making some assumptions about [working families] now. Number one, that there are two parents or that there’s a parent there at all. We have to start addressing some things as a community, as a society, and stop passing the buck, passing the blame.”

GEAR UP Alabama’s 21 school districts and 13 community partners are shooting for ambitious, big-picture changes. It’s too early to tell whether it’ll help more poor kids get beyond high school. But in places it’s been around long enough to yield data (see section staring on page 119), there are signs the approach works. Though the numbers are complex (see also here), GEAR UP’s been linked to increased graduation rates, knowledge of college, and higher education enrollment.

There’s still a tremendous amount of work to be done, but a diverse network of organizations and educators are pushing ahead. And people directly affected are hopeful. That includes Ashton’s Bridges’ father, Eddie Bridges.

“Well, in the long term, it should better him as a person,” he says. “He gets a chance to meet all different people … from all different walks of life.”

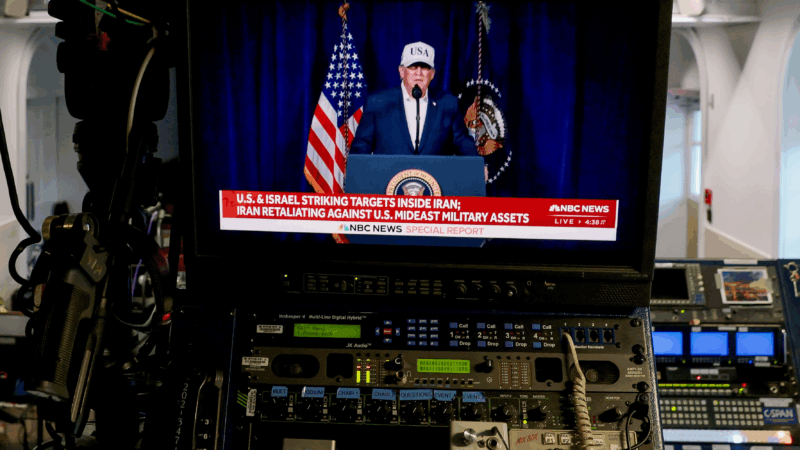

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.