Shaping History with a Camera

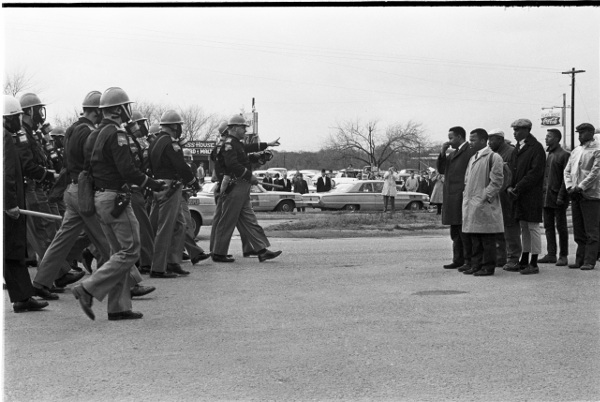

Spider Martin's most well-known photograph called "Two Minute Warning" shows marchers facing a line of state troopers in Selma moments before police beat the protestors on March 7, 1965. The day became known as Bloody Sunday.

In March, Selma will mark the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. That’s the day police beat demonstrators attempting to march to Montgomery in support of voting rights. Saturday an exhibit opens in Selma of some of the most iconic images of that day. They’re from the late photographer Spider Martin.

Martin’s real introduction to the civil rights movement came on a late night at home in February 1965. He was a 25-year-old photographer for the Birmingham News.

“About midnight I get this phone call from the chief photographer and he says ‘Spider, we need to get you to go down to Marion, Alabama.'” Martin said in a 1987 video. “Says there’s been a church burned and there’d been a black man who was protesting killed. He was shot with a shot gun. His name was Jimmie Lee Jackson.”

Martin says he got the call because he was the youngest staff member and no one else wanted to go. That assignment would lead to his most famous work.

Plunged into Civil Rights

James “Spider” Martin grew up in Hueytown. He was small in stature and he earned the nickname “Spider” for his quick moves on the high school football field. He trained as a fine artist but switched to photography because he could make more money.

His daughter Tracy Martin says he probably wasn’t aware of the brutality civil rights protestors faced at the time because southern newspapers generally played down the conflict. She says once he started covering the Jimmie Lee Jackson case, things changed.

“He realized that it was history and that it was important,” Tracy Martin said. “He got wrapped up in it.”

Jackson’s killing helped spur the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights marches a few weeks later. Spider Martin was in Selma for Bloody Sunday when state troopers attacked protestors. Holding a camera made him just as much a target. He recounted in an interview with Alabama Public Television, what happened when a police officer saw him.

“He walks over to me and, plooow! Hits me right here in the back of the head. I still got a dent in my head and I still have nerve damage there,” Martin said. “I go down on my knees and I’m like seeing stars and there’s tear gas everywhere. And then he grabs me by the shirt and then he jerks me up like this. He’s got his club like this and looks straight in my eyes and he just dropped me and said, ‘scuse me. Thought you was a nigger.'”

Alabama authorities were not happy Martin’s pictures were being distributed around the country. One trooper told him then Governor George Wallace had ordered Martin be harassed that day.

Looking Back 50 Years Later

A few blocks away and 50 years later, some of those photos hang in a repurposed auto service center that’s the home to ArtsRevive, a Selma arts organization. This exhibit of Spider Martin photographs includes his most noted pictures from the marches.

But ArtsRevive executive director Martha Lockett says some of her favorites are less recognized. She points out a close-up of an officer’s leg with his billy club.

“It’s very still, but very energetic,” Said Lockett. “You know what’s getting ready to happen and to me that’s one of the most dynamic pictures that’s in the show.”

That artistry was calculated according to Morehouse College history professor Larry Spruill. He says Spider Martin was one of a handful of photographers on what’s dubbed the “segregation beat.” They were mostly college-educated white men in their 20s who reflected the liberal optimism of a post-World War II generation.

“They took complex issues layered in race and made them very simple,” said Spruill.

Spruill says Martin Luther King Junior understood the power of visuals and tipped off photojournalists. While the optics of Bloody Sunday were credited with shocking middle America and leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, the pictures were considered disposable back then. That was partly because in the mid-60s, photojournalism was beginning to take a back seat to the flash and immediacy of television. Spruill says he found pictures newspapers didn’t run with holes punched through them.

“It’s like finding original copies of important American history documents trashed,” said Spruill

A similar thing happened to the photographers. Spider Martin’s daughter says it was decades before he became known for his civil rights pictures.

He died in 2003 and she says he’d be excited about exhibiting his work around this 50th anniversary. But from the interview with Alabama Public Television, it’s clear attention on him was an uncomfortable fit.

“I mean it’s kind of fun sometimes being a celebrity you might say or a little bit famous,” Spider Martin said. “But then again, I’d rather not be famous.”

Still the attention he offered through his camera, helped shape American history.

“Spider Martin Retrospective: Exploring the Role of Photojournalism in Influencing History” opens February 7th at ArtsRevive in Selma, Alabama. It runs through March 28.

Parents, are you sure your kid’s car seat is installed right? Here’s how to know

In this visual guide, certified car seat experts walk through common installation mistakes and how to fix them. Learn what a secure car seat base and a tightly fastened tether look like and more.

Trump announces ‘major combat operations’ in Iran

Israel and the U.S. have launched strikes against Iran, with explosions reported in Tehran and air raid sirens sounding across Israel.

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

How the federal government is painting immigrants as criminals on social media

Experts say this kind of media campaign is unprecedented and paints a distorted picture of immigrants and crime

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve