Remembering The Death That Sparked The Selma Marches

This week marks the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, the day police in Alabama beat marchers going from Selma to Montgomery in support of voting rights. Less well-known is the violent confrontation that sparked the Selma marches. It happened a few weeks earlier during a demonstration in Marion, a small town near Selma. A black civil rights activist named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed.

The Zion United Methodist Church in Marion was packed on a recent weekend. People wearing their Sunday best clapped, cheered and honored Jimmie Lee Jackson. Fifty years ago, the 26-year-old Vietnam veteran and Baptist deacon was shot by an Alabama state trooper after what was supposed to be a peaceful demonstration.

“Let’s get some spirit up in here in honor of Jimmie Lee Jackson who died for us!” yells Bobby Singleton, revving up the crowd. Singleton says Jackson’s death is an overlooked turning point in the voting rights story.

“Freedoms that we enjoy are on the backs of Jimmie Lee Jackson! So let’s give him some praise up in here today,” Singleton says, to cheers.

Billie Jean Young is a professor at Judson College in Marion and author of a play on Jackson’s life. “People like to, I think, feel that things started with Selma,” says Young. “But people in Marion are well away we had our own voting rights campaign here.”

Young says Jackson was involved, inspired after hearing his 82-year-old grandfather talk about wanting to vote.

Marion’s voting rights campaign held a series of demonstrations in February of 1965. On February 18, James Orange, an organizer for Dr. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was arrested and thrown in the Perry County Jail, just a block down the street from the church.

“People crowded Zion Church that night,” says Young. “They were very upset — not just that he was jailed, but that there was talk that they planned to kill him.”

Hundreds of demonstrators tried to march from the church to the jail, but they didn’t make it far. Walta Mae Kinnie was there.

“Half of us had gotten out of the church, and some had marched, started toward the jail. And they shut the lights out. The city turned the lights out,” remembers Kinnie.

Alabama state troopers, local law enforcement and a mob of angry white residents met them outside.

“They beat people and ran them every which way,” recalls Kinnie.

Kinnie says she and many others still have scars from that night. According to news accounts, the marchers weren’t armed. Black Marion residents were attacked and beaten with billy clubs, whether they were marching or not. Jackson was shot in a cafe where witnesses said he was trying to protect his mother from beatings. He died a week later.

The people in Zion Church came to remember what history often forgets. Unlike the Selma march a few weeks later, there are no iconic photographs of that night. Journalists were beaten, their cameras smashed. But word got out. A segregationist newspaper even called Marion a nightmare of state police stupidity.

From there, Billie Jean Young says the story goes, someone said “Well, we need to take his body to Montgomery and give it to George Wallace,” the governor of Alabama.

Albert Turner Jr. is the son of an organizer of the Selma march. He says Jackson’s death was the catalyst for the marches to Montgomery.

“He was not a rabble-rouser,” says Turner. “He was an individual whose death summarized the extent that this country and this state would go to to keep African-American people from becoming full-fledged citizens.”

C.T. Vivian of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference escaped the violence that night in 1965, but he returned to Marion for this service. He says what happened in this city will forever hold a strong place in his heart and the movements.

“Anytime anybody is killed,” says Vivian, “That should be the cry for everyone to speak to the fact that only life is worth dying for. It sounds strange, but it is true.”

The cafe where Jackson was shot is gone, but a plaque honors him nearby. The Alabama state trooper who killed Jackson wasn’t indicted until 2007. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and served six months in jail.

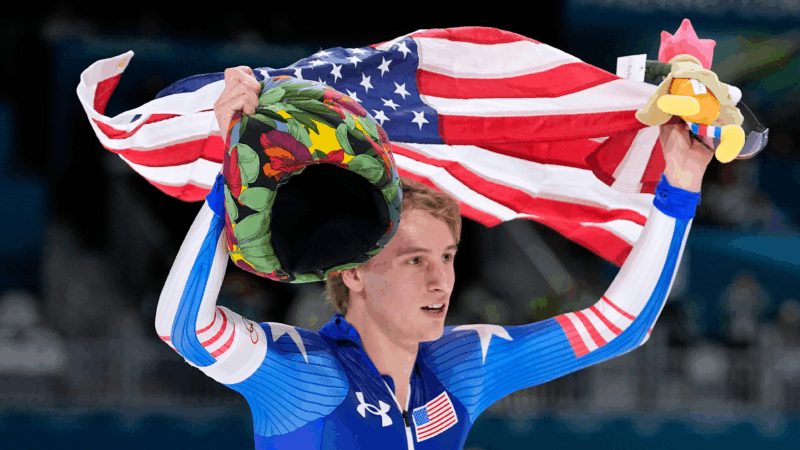

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

How the FBI might have gotten inaccessible camera footage from Nancy Guthrie’s house

Last week, law enforcement said video footage from Nancy Guthrie's doorbell camera was overwritten. But the FBI has since released footage as Guthrie still has not been found.

How to hone your ‘friendship intuition’

Friendship expert Kat Vellos shares tips on how to make a new friendship stick, including what to do together, how often to hang out — and what to do if the vibes just aren't there.

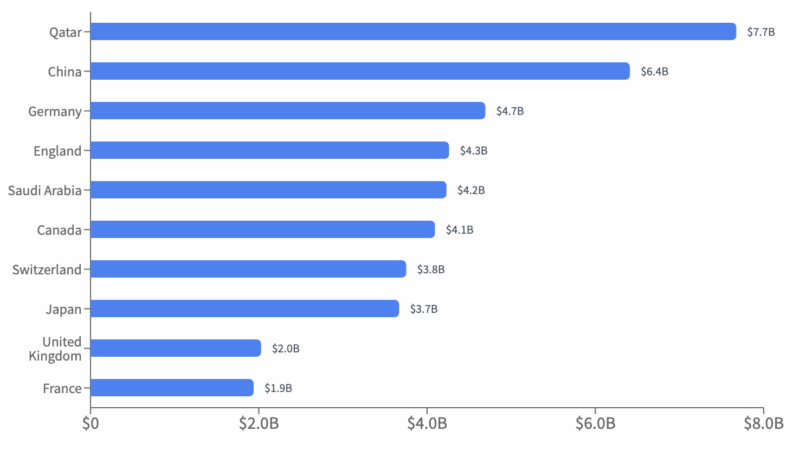

US Colleges received more than $5 billion in foreign gifts, contracts in 2025

New data from the U.S. Education Department show the extent of international gifts and contracts to colleges and universities.

Free speech lawsuits mount after Charlie Kirk assassination

Months after the killing of Charlie Kirk, a growing number of lawsuits by people claim they were illegally punished, fired and even arrested for making negative comments about Kirk.

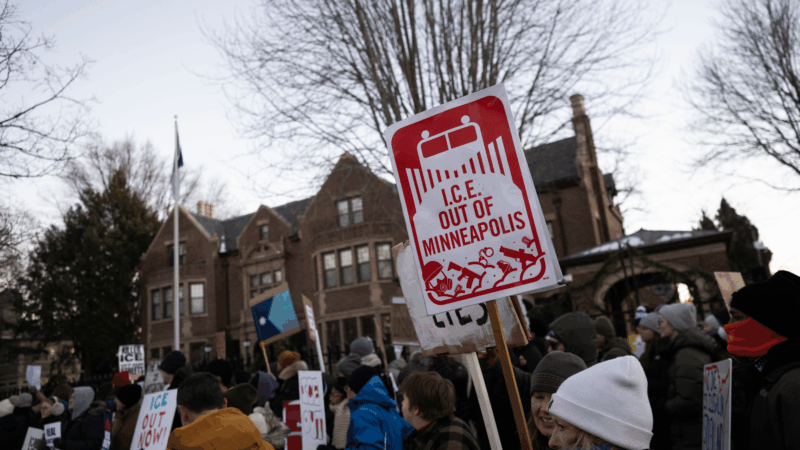

Swing voters in Arizona say they want to see ICE reformed

Concerns about the tactics of federal immigration agents remain front of mind for some key voters who supported President Trump in 2024.