Fighting Heroin Abuse and Overdose Deaths

Heroin use has exploded in Alabama, with heroin-related deaths more than doubling in Jefferson County last year. All this week, WBHM explores the problem in our series “Heroin in Alabama.” We’ll hear what schools, law enforcement, the courts, and others are doing to fight heroin abuse and curb overdose deaths. To start, WBHM’s Rachel Osier Lindley explains the scope of the problem and how we got to here:

Beth Bachelor says she’ll never forget the time in her life when she was abusing drugs and opiates. But she still has trouble explaining it.

“I remember my father asking me once if I was possessed at one point. And I can tell you, it was probably close,” she recalls. “And I can understand why I was asked the question.”

Bachelor describes her younger self as a “trash-can addict: who mixed prescription pain killers, alcohol, anything really.”

“Nothing else matters as much as that. You’re just constantly distracted by getting, using, having, having enough,” says Bachelor.

But after overdoses and time in the hospital, Bachelor got help. For more than 25 years now, she’s worked at Fellowship House, a residential drug abuse treatment facility in Birmingham.

She runs the recovery program there, and recently, she’s seen a big change in their clientele.

“Previously maybe three to five percent of our population were IV opiates, which is heroin now. Now it’s about 20 percent.”

Numbers seem to be going up everywhere. Federal statistics show a rise nationally in heroin use since 2007. It’s been going up across Alabama in recent years. Heroin can be injected, smoked, or snorted, and causes feelings of euphoria.

In Jefferson County, the coroner reports heroin caused or contributed to 144 deaths in 2014. The year before, that number was in the fifties.

“Every single one of those deaths is a tragedy to that family,” says Joyce Vance, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama.

Last year, the Justice Department made combating heroin and opiate drug use a priority, calling it an “urgent public crisis.”

“I’ve talked to too many families now whose path to addiction in many cases was through drugs that were prescribed to them for pain after surgery,” says Vance.

She says it’s a common story. Once doctors stop refilling pain killer prescriptions, people look for other ways to get that feeling. Or young people, who have taken pain pills not prescribed to them, make the jump to heroin. Vance says heroin is cheaper than ever, about $20 for one hit.

And heroin doesn’t discriminate.

“It crosses all socioeconomic and racial lines,” says Judge Shanta Owens, who presides over Birmingham’s drug courts. And she sees all kinds of users in her courtroom.

“I am constantly preaching to the African-American Community that heroin is not just a white drug,” explains Owens. “And I am constantly preaching in affluent communities that heroin is not a drug that you just see in poverty stricken households or communities.”

While almost 90 percent of Jefferson County’s heroin-related deaths in 2014 were white people, heroin did kill about as many people in majority-black Bessemer as in majority-white Vestavia Hills.

U.S. Attorney Joyce Vance says everyone needs to be on guard — not just law enforcement, but teachers, families, and pharmacists, too.

“We’re all working together to do outreach in the community to try to warn people that heroin is back,” stresses Vance. “We need to take action to build awareness.”

Fellowship House’s Beth Bachelor worries not just about heroin’s greater availability and popularity but the strength of today’s heroin.

“You get something with the kind of purity level that’s out on the street, the first few people that use it that overdose, some of them don’t make it,” says Bachelor. She says there’s a great need for more funding for treatment. Fellowship House’s waiting list is long, and Bachelor says not getting heroin users into treatment can be a death sentence.

“Every time there’s a new batch of something on the street some people die,” Bachelor says.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.

They’re cured of leprosy. Why do they still live in leprosy colonies?

Leprosy is one of the least contagious diseases around — and perhaps one of the most misunderstood. The colonies are relics of a not-too-distant past when those diagnosed with leprosy were exiled.

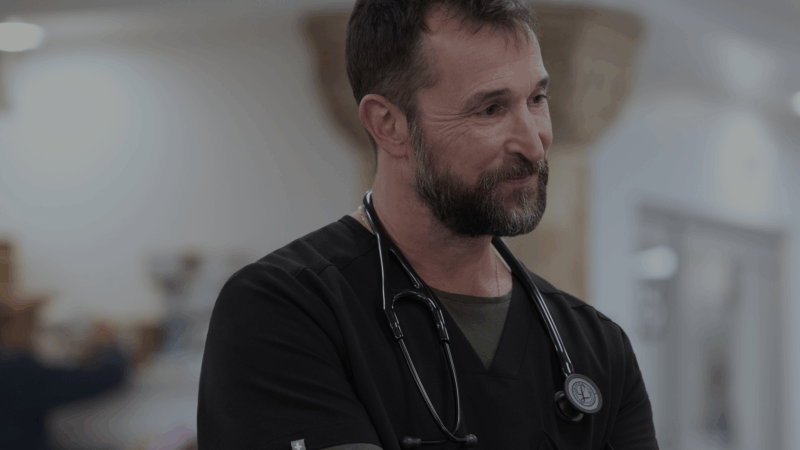

This season, ‘The Pitt’ is about what doesn’t happen in one day

The first season of The Pitt was about acute problems. The second is about chronic ones.

Lindsey Vonn is set to ski the Olympic downhill race with a torn ACL. How?

An ACL tear would keep almost any other athlete from competing -- but not Lindsey Vonn, the 41-year-old superstar skier who is determined to cap off an incredible comeback from retirement with one last shot at an Olympic medal.