Debate Over Confederate Monuments, In Birmingham And Beyond

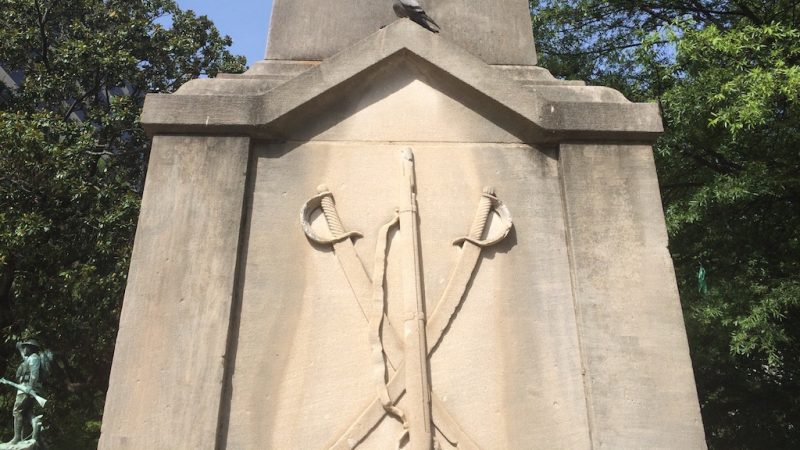

A pigeon rests on the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors monument in Linn Park in downtown Birmingham.

Before last month’s church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, which left nine African Americans dead, the suspect posed in pictures with the Confederate battle flag. On Friday, South Carolina removed the flag from statehouse grounds. Now other cities across the South, including Birmingham, are reexamining the way they honor that and other symbols of the Confederacy.

On a sunny Alabama morning, the 90-degree heat doesn’t stop Cynthia Alexander from taking a brisk walk.

“I do a lot of walking ‘cause it’s good for my health,” says Alexander. “Yeah, I just love to walk.”

One of her favorite routes is past Linn Park in downtown Birmingham. City hall and the county courthouse look out onto it. And, at the entrance to the park, stands a 52-foot-tall obelisk-style statue. I ask Alexander what it is.

“Um…I really don’t know,” she says. “But it looks like it’s been there for a while.” She says she hadn’t thought about it before. But one thing is clear:

“Obviously the pigeons love it, they on it.”

The birds are on a Confederate Soldiers and Sailors monument, and it has been there for a while. For 110 years. Alexander’s not alone in overlooking it. Unlike the distinct stars and bars, Confederate monuments come in all shapes and sizes, an often-overlooked part of Southern scenery. But not to everyone.

“That monument needs to go,” says activist Frank Matthews. He’s tried to get the monument removed for years. He says it’s a powerful symbol of hate.

“If a picture’s a thousand words,” he says, “a monument’s a million words.”

Birmingham’s Park and Recreation Board asked the city’s lawyers if there are any legal issues involved in removing the monument. They expect to hear back this week. Other cities, from New Orleans to Memphis to Austin, are making similar moves. Matthews is glad the cause is gaining traction.

“The trunk of embedded racism of the Confederacy is epitomized in those 100-year-old statues,” says Matthews.

But it’s not as easy as lowering a flag. The statues are big, old, and expensive to move. Birmingham says they’d consider giving the monument to a Southern heritage group if they’d pay relocation costs.

But some don’t see them as racist symbols, and some think it’s silly to spend time and money moving them. Nell Clay, an African-American woman, works in downtown Birmingham and passes the Confederate monument almost every day.

“It’s history. And it’s history for our children. Black and white,” says Clay. “I’m not offended by it in any way. It’s just a part of this park.”

Birmingham City Council President Johnathan Austin says, yes, Confederate monuments reflect history, but it was a different time politically and socially.

“There is no place for those monuments in our society other than in museums,” says Austin.

Austin says it’s important for people in power to reexamine Confederate imagery in public spaces. Especially in a place like Birmingham.

Just a few blocks away is Kelly Ingram Park, where police blasted peaceful protesters with fire hoses during the Civil Rights Movement. That park is home to a different kind of monument – one honoring four girls killed when the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963.

Like Charleston, that tragedy brought racial hatred and violence to the forefront of national conversation. Though today, many say that conversation doesn’t go deep enough.

“It’s much easier to discuss taking down a monument than it is to talk about institutionalized racism,” says Ahmad Ward of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

While the Institute hasn’t taken a stand on Confederate monuments, Ward says people should talk about how racism still shapes the nation.

“That goes to the heart of things we don’t really want to touch. And it makes us second-guess what we stand for as an ideal for an American society,” says Ward. “And that makes people uncomfortable.”More uncomfortable than any statue.”

Back in Linn Park, Cynthia Alexander sits a few feet from the Confederate monument, resting up for the second half of her walk. She shrugs.

“It’s not that I don’t care about it,” she says. “It’s just that it’s been there for a long time. If it’s not broke, why should you try to fix it?”

That’s the question facing many communities across the Deep South right now.

Suspect in attack at Michigan synagogue is dead, officials say

Security officers at Temple Israel had "engaged the threat" that apparently started with a vehicle ramming into the building, according to Oakland County Sheriff Mike Bouchard.

This tale of a Chicago school book ban was inspired by true events

Librarian Jarrett Dapier's graphic novel tells a fictionalized account of real-life events in 2013 that restricted access to Marjane Satrapi's memoir Persepolis in Chicago Public Schools.

Senate passes bipartisan housing bill targeting large investors and easing regulations

The 21st Century ROAD to Housing Act would ban large investors from buying up single-family homes.

Chilean Smiljan Radić Clarke wins architecture’s highest honor

The Pritzker Prize was awarded Thursday. "In every work, he is able to answer with radical originality, making the unobvious obvious," said fellow Chilean architect and prize chair Alejandro Aravena.

El Niño is set to take hold this summer, driving up global temperatures

A potentially strong El Niño weather pattern will likely emerge this summer and persist through the rest of the year. The hottest years on record generally occur in years when El Niño is active.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.