Sustainability: The Problem with Alabama’s Water Management

Compared to most states, water is plentiful in Alabama. In fact, you can see the many rivers that cross Alabama right on the state seal. But there are some who say Alabama is doing a poor job of managing this resource.

Heather Elliott is among them.

“Basically we have a 19th century legal system and we’re trying to deal with 21st century problems,” Elliot said.

Elliott researches water law at the University of Alabama. She says Alabama uses the riparian doctrine. That means if your property touches a lake, river, or stream, you can use that water on your land. You can capture rain or ground water too, but you can only do this as long as it doesn’t cause harm to other landowners.

“So if you start pumping, one of your neighbors could come along and say, ‘You’re pumping too much. You’re harming my right to the water,'” said Elliott. “And that’s when you go to court.”

So we’re left with a system where people, utilities, and companies kind of do what they want until there’s a conflict. Then the courts sort it out. The courts essentially make the state’s water policy. Elliot says that’s cumbersome and inefficient.

“Courts are terrible at thinking ahead,” said Elliott. “Their whole job is to look backwards and resolve disputes between people that have already happen. There’s nothing in the current law that allows avoiding problems before they happen.”

Potential Problems

Such a legal structure causes several problems according to Mitchell Reid. He’s with the environmental group Alabama Rivers Alliance. First, when there’s a water crisis, such as the droughts of 2008 and 2009, there’s not a way to make sure water’s being distributed equitably.

“You certainly have big water users with big pumps who could pull out more water and they were maybe not under the gun as much as others,” said Reid. “But then you had some places such as Alexander City which found themselves in a situation where their water intakes were high and dry and they were literally without water until they could move a water intake.”

Second, there’s little predictability. Reid says if you’re an industry that depends on water, you’d don’t have any assurances you’ll get a fair shake when there are water shortages.

Those water issues are very real for Cullman County farmer Darrel Haynes.

He’s weathered his share of droughts on his family farm where his sons represent the fifth generation. Talk of damming a nearby waterway concerns him because he doesn’t have high-powered lawyers to ensure his water rights.

“I think the state has some responsibility in the fair allocation of water,” said Haynes, despite calling himself a small government kind of guy.

An effort is underway to craft a statewide comprehensive water management plan. In 2012 Governor Robert Bentley created a working group tasked with making recommendations on a water plan. They took input from many stakeholders including farmers, business, utilities, environmental groups, academics, and state agencies. The group made its recommendation to the governor in December and the idea is the legislature will adopt a plan in a future legislative session.

Where’s the Report?

But it’s now March and those recommendations have not been made public. The Alabama Rivers Alliance’s Mitchell Reid says there was an expectation this report would be presented publicly. Because it’s still secret, Reid says that raises questions of transparency and manipulation.

“I think that that does a lot to, I guess, call into question how fair this system is going to be for all of the people of Alabama,” said Reid.

Darrel Haynes says he has friends who have asked for copies of the report but haven’t gotten a response. He has his suspicions.

“Alabama Power would love for there to be no water plan because they’ve enjoyed no water plan,” said Haynes. “They’ve enjoyed riparian rights that this state has operated under for many, many years.”

Alabama Power does play a major role in managing water through 11 company owned lakes that produce hydroelectric power. A spokesman declined to be interviewed but in a statement says they operate under the rules of federal regulators. He adds the company submitted comments to the water working group and believes any water plan should be based on a comprehensive and scientific assessment of the state’s water resources.

A spokeswoman for Governor Bentley says he did receive the recommendations in December but won’t release them publicly until he’s reviewed them. She would not say when that might happen.

As the waiting game continues there’s one more issue from a lack of a comprehensive water plan. It has to do with the more than 20-year water war that continues among Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. They’re fighting over some common waterways including Lake Lanier in Georgia and the Chattahoochee and Tallapoosa Rivers.

“The Supreme Court takes a very dim view of states that don’t manage their own resources well,” said University of Alabama law professor Heather Elliot.

Elliot says Florida and Georgia regulate water, so the Supreme Court could say to Alabama….

“You don’t look like there’s that much trouble going on. You’re not willing to clean up your own house. Why should we clean it up for you?” said Elliot.

The state’s essentially fighting with one hand tied behind its back. Another reminder that the future of Alabama’s water may have less to do with what’s in rivers and streams and more to do with politicians and lawyers.

~ Andrew Yeager, March 18, 2014

| SUSTAINABILITY: What is Sustainability?

| SUSTAINABILITY: What is Sustainability?

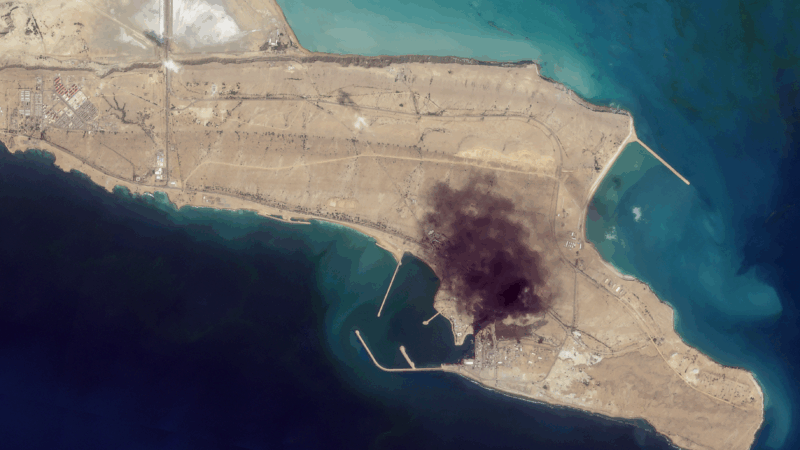

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.