Segregation Academies: Past And Still Present

Ever since the Supreme Court declared segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954, the racial makeup of our schools has been in flux. Forced integration made the South’s public schools some of the most integrated in the country, but now — here and across the nation — our schools are re-segregating. The Southern Education Desk is taking a deep look at the issue with a multi-part series exploring this complex trend. In the second installment, WBHM’s Dan Carsen goes back in time to examine a strategy whites once used to sidestep public school integration, one that still shapes communities today: private so-called “segregation academies.”

In west-central Alabama, not far from grazing cattle and ubiquitous forest, there’s a selective, highly

regarded private school. Pickens Academy serves an area so rural it puts on deer hunts to raise funds. It

also serves the college-bound children of the area’s white movers and shakers. For many of them,

Pickens Academy is a family tradition. It’s a sheltering, supportive place.

Fifth-grader Charlie Wilson says, “I like it that everybody knows each other, so that everybody’s real close.” Senior Katie McKinzey adds, “I love the closeness of it — how we’re all like a family. There’s not many students who go here, but we all

come together.”

That kind of bonding seems to come naturally to the roughly 270 students. It probably doesn’t hurt that

they share a culture, a heritage, and an optimistic mindset.

Pickens Academy was founded in 1969. Former assistant headmaster Connie Marine taught there for 27

years. Her daughter teaches there now and all four of her grandchildren are students. I asked

her why people started the school:

“I think it was more about quality. ‘Separate but equal’ does not always mean ‘equal.’ And the

influx was going to bring down — in the minds of many — the quality of education.”

It’s hard to know how many “seg academies” there are because different states keep different data on private schools —

some of it spotty — and because some schools founded during those decades actually were started for religious reasons rather than just using that as cover. But it’s safe to say, although many seg academies have folded, hundreds remain across the South.

They’re legally forbidden from discriminating now.

“What it began as 40 years ago is not what it is today,” says Marine. “It’s open admission.”

Even so, Pickens Academy has one black student in a county whose under-eighteen population is more

than half African-American. Some blacks worry their children wouldn’t be welcomed at a seg academy,

but cost is an obstacle, too.

“You are in West Alabama, and that’s … it’s a poverty area,” says Marine.

On top of taxes, Pickens Academy families pay for tuition and other expenses, like the school’s bus and

minivan, computer labs, and a new $40,000-dollar science lab.

But Back On The Other Side…

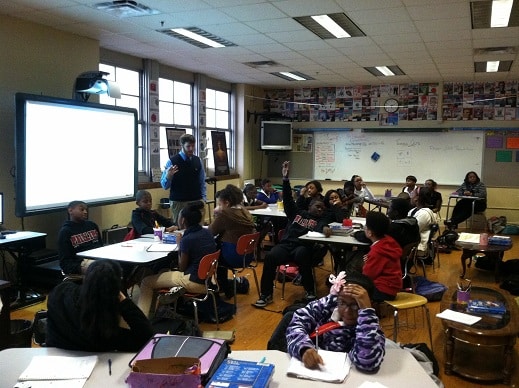

Now jump to a place on the other side of many divides, a place that looks very different from Pickens Academy — Birmingham’s Phillips Academy. It’s a good public school, but it’s also part of the type of district seg academy founders were trying to avoid.

Birmingham’s 95-percent-black system competes with seg academies and whole “seg districts” —

suburban public systems that split off for much the same reasons. As in rural areas, the separation from

whites is almost complete. And the kids know it.

“It’s better to have a diverse school,” says seventh-grader Khiara Bush, “because if you grow up around diverse people, then, when

you get older, and like have jobs with diverse people, you know how to work with them better.” She says she likes her school, but she wishes it was more diverse.

This “dual” education system exemplified by Phillips and Pickens is often most

pronounced in rural and inner-city places that really can’t afford to divvy up money, political pull, or other resources.

University of Alabama at Birmingham historian Robert Corley explains where he sees the trend going:

“We’re going to have certain schools that will end up having to take everybody that comes

through the door. And everybody else is going to get the best we can offer, because they’ll pay for it,

either through higher taxes or tuition. It’s a very inefficient way to provide services.”

If that’s true, it’s a handicap on the South, and increasingly, the United States: Thanks to court decisions,

the ending of federal desegregation orders, and broad demographic changes, the nation’s schools are re-segregating.

Corley and other experts say the “dual-school” system so common in the South is likely a preview of

where the nation is going. Or returning.

In the shadow of the Olympics, migrants search for a welcome in Milan

As Italy cracks down on migration, Milan takes a different path — offering shelter and integration to asylum seekers even as the central government tightens borders and funds deterrence abroad.

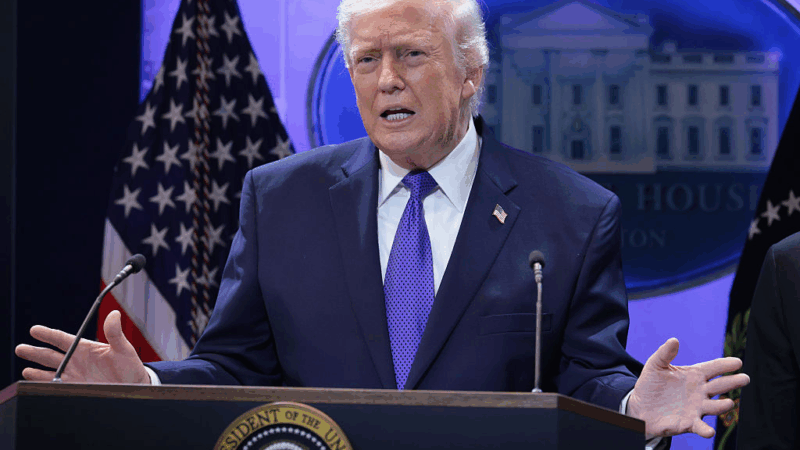

Trump to raise global tariffs. And, most say the state of the union is weak, poll says

President Trump says he is raising global tariffs to 15%. And ahead of the president's address tomorrow, most Americans say the state of the union is not strong, according to an NPR poll.

U.S. has a quarter fewer immigration judges than it did a year ago. Here’s why

The continued drain of personnel from the already strained immigration court system has contributed to depleted staff morale, mounting case backlogs — and floundering due process.

The owners want to close this Colorado coal plant. The Trump administration says no

The Trump administration has ordered several coal plants to keep operating past their planned retirement, part of a larger effort to boost the coal industry. Two Colorado utilities are pushing back.

Influencers are promoting peptides for better health. What’s the science say?

The latest wellness craze involves injecting these molecules for athletic performance, longevity and more. Scientists say the research isn't keeping pace with the health claims.

Poll: Most say the state of the union is not strong and the U.S. is worse off

Ahead of the State of the Union address on Tuesday, evidence continues to mount that President Trump is facing political headwinds.