Money Tight, Scientists Turn To Crowdfunding

Birmingham, Ala.– In the past decade, it’s gotten much harder for scientists to get the federal grants that fund the vast majority of American research. This year’s sequester has made it even more

Birmingham, Ala.– In the past decade, it’s gotten much harder for scientists to get the federal grants that fund the vast majority of American research. This year’s sequester has made it even more

difficult, and the government shutdown is likely to slow things down even

further. So scientists are looking for new ways to pay for their work, including

“crowdfunding.” But going online and asking the public for money has real

drawbacks. Even so, as WBHM’s Southern Education Desk reporter Dan Carsen tells us, some think it could open up the field in a good way:

Science is about the pursuit of knowledge, but working scientists will tell you there’s a lot more to it. The

politics reach from local labs to the U.S. Congress. And then there’s the money-scrounging. Research

dollars boost the whole economy, but that doesn’t mean there’s enough funding out there to run labs or

find cures.

“Researchers with great ideas, with a lot of potential, that can save lives, don’t get

enough funding to bring these treatments to the people who need it the most,” says

Hoover native and former cancer researcher Larry Lawal. He worries that while we’re cutting

science budgets, other nations are expanding them. So he recently left UAB medical school to start a

new company called HealthFundIt.

“People who care about different diseases can go online, connect with researchers

doing groundbreaking work, and donate a small amount,” he says. “It’s to democratize funding, and give

everyday people a voice and a chance to make things happen.”

Lawal’s company will have expert scientists reviewing proposals. But that’s not how it’ll work

everywhere, and even pro-crowdfunding experts see a problem. Claremont University research policy

expert David Drew is one of them.

“There could be money wasted on projects that are ridiculous,” he says. “Unlike submitting a

proposal to the National Science Foundation, [or] the National Institutes of Health, there’s no quality

review of the scientific merit of the idea.”

Still, Drew thinks crowdfunding’s benefits outweigh that risk because it’s spread among voluntary

investors. And he says expert review will happen later in the process as researchers try to get published.

But in the bigger picture, many doubt crowdfunding could raise, say, twenty million dollars for a clinical

drug trial. And making ideas or data so public opens them up to theft. And finally, there’s the issue of safety if research is done without traditional oversight.

“If the research is being done by someone at a university, there’s a good chance it’ll be

reviewed by their I.R.B. — institutional review board,” says Drew. “But with crowdfunding, possibly not. And it is

of vital importance.”

It all depends on the particular companies, most of which are still evolving. But at UAB there’s a social scientist who’s already had crowdfunding success: Pia Sen

raised twenty-two thousand dollars for gun policy research through an online portal called Microryza. I

asked her if crowdfunding could take scientific merit out of the equation and make research a popularity

or public-relations contest. She doesn’t think so.

“Here, I’m putting out a proposal for all the world to see, including my peers,” she says. “I think

the fear of being made to look like an idiot in front of your peers is a good deterrent for not

putting up anything that’s absolutely terrible.”

More and more researchers say today’s funding climate is pushing them toward unconventional

sources. One told me competition for grants is “like something out of Thunderdome.” Another says

we’re close to “losing a generation of scientists.” But Drew thinks crowdfunding will help less-established

researchers who go against conventional wisdom. And he’s got a well-known example:

“Einstein went to work in the patent office in Switzerland because he did not get the

university jobs that he wanted. And, from this unlikely spot, he produced the most important

research and theorizing of the twentieth century. There are all kinds of people out there with creative ideas,

and the more resources we have to fund them, the better.”

Especially after this year’s sequester cuts, researchers say it’s a bad time to have a good idea.

Crowdfunding could help change that. And that might benefit us all, assuming next year doesn’t

become a good time to have a bad idea.

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.

Danish military evacuates US submariner who needed urgent medical care off Greenland

Denmark's military says its arctic command forces evacuated a crew member of a U.S. submarine off the coast of Greenland for urgent medical treatment.

Only a fraction of House seats are competitive. Redistricting is driving that lower

Primary voters in a small number of districts play an outsized role in deciding who wins Congress. The Trump-initiated mid-decade redistricting is driving that number of competitive seats even lower.

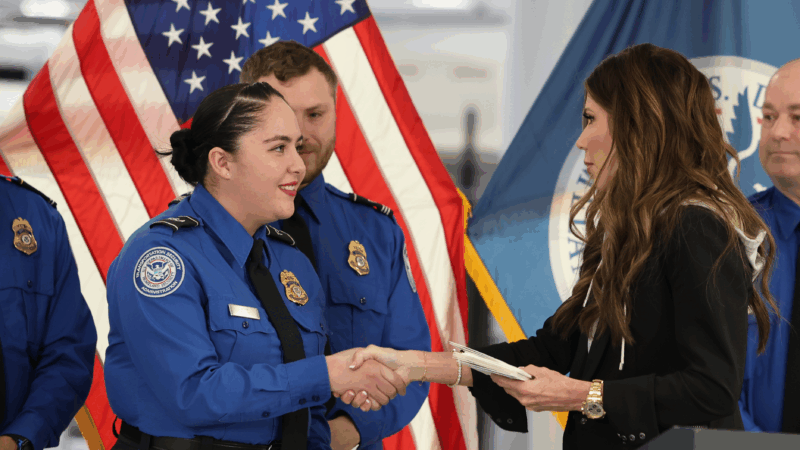

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.