Black School, White School: Teaching The Civil Rights Movement

One of many Birmingham Civil Rights Institute exhibits that show the separation of black life and white life. Differences in the teaching of that history remain.

Most people know Birmingham was a Civil Rights Movement battleground. But how is that complicated history taught in schools today? And are there differences between white and black districts? As part of our special Civil Rights anniversary coverage, Southern Education Desk reporter Dan Carsen went to class in urban Birmingham and suburban Mountain Brook to find out. Read below, or listen above.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, Alabama schools teach the Civil Rights Movement better than those of any other state. But zoom in to the district level and it’s all over the map. Birmingham City Schools are 95% Black, but in nearby Mountain Brook, the student body is 98% white. You might expect differences in how Civil Rights history is taught, and according to social studies teacher JohnMark Edwards, you’d be right.

“It’s certainly different teaching white kids about the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “You might have a poster, you might have an activity, but it’s not the theme like it is in a black school. It’s two different heritages.”

Edwards attended relatively wealthy white school systems and student-taught in several, including Mountain Brook. His masters thesis was on resistance to school desegregation in and around Birmingham.

Now he teaches in the building Fred Shuttlesworth almost died trying to integrate — Phillips Academy, a 98% Black K-8 magnet school. He imparts the lessons of the Movement through lectures, art, role-playing, and field trips. But even at a black school with high-achieving students, distance in time breeds unfamiliarity.

“I’m always shocked by the things I’m able to teach them as brand new, fresh, never heard this before,” he said.

Sam Pugh of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute is trying to remedy that. I catch up with him after he captivates a gym full of students with a group tug-of-war between “freedom” and “the establishment.” He offers a partial explanation for the spottiness of Civil Rights education:

“Because the history is harsh, I think a lot of people try to avoid it,” he says, adding that it’s easier to avoid in communities where the majority of people weren’t on the receiving end of the persecution. He goes on, “I think there’s something about America where we don’t want to hear about the bad side of America.”

But Mountain Brook High School history teacher Joe Webb plows right in. He hits key facts and makes no

bones about sharing personal impressions, including his thoughts on Rosa Parks.

“What I don’t get,” he tells his class, “… somebody asked a lady to get up … My dad today would come out of his grave and get me. If she’s a Martian, it doesn’t matter — get your little self up!”

On the landmark Brown versus Board of Education school desegregation case, he explains, “This says ‘separate is not equal.’ Why is it that people would change their mind that drastically? Generations at times change. My grandmother was awful about this. She was racist as all-get-out. My mother was better than that, I’m better than that, and my kids are awesome: a Ukrainian and two Mexican guys — that’s his peeps, that’s who he hangs with.”

Despite differences in approach, whether students are in Birmingham or Mountain Brook, they seem to grasp the significance of that societal change. Mountain Brook junior Laura Screvens says,”It’s definitely important to learn about because it’s great to know about your history and where you come from, and not to repeat it, and how to treat people like they need to be treated.”

Birmingham Phillips Academy seventh-grader DeVaun Jemison also makes the connection from history to herself.

“They were sacrificing their lives and risking their lives just to … basically get what they deserved, which is freedom and fairness, in order for us to have a better life.”

Almost every adult and student I spoke with says knowing Civil Rights history makes us less likely to return to society-wide persecution, of any group. It seems that learning this key part of America’s past has ramifications beyond report cards.

With decades-long restrictions lifted, a Pakistani brewery has started exporting beer

Drinking is illegal for Pakistan's Muslim majority, but Murree Brewery's beer has long been available to non-Muslims and foreigners there. Now it's being exported to the U.K., Japan and Portugal. Is the U.S. next?

A red hat, inspired by a symbol of resistance to Nazi occupation, gains traction in Minnesota

A Minneapolis knitting shop has resurrected the design of a Norwegian cap worn to protest Nazi occupation. Its owner says the money raised from hat pattern sales will support the local immigrant community.

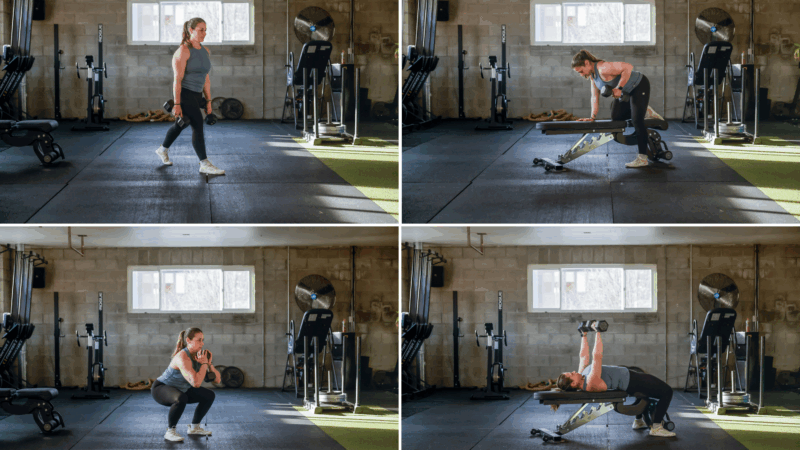

Want to get stronger? Start with these 6 muscle-building exercises

If you're curious about starting a resistance training routine and not sure to begin, start with these expert-recommended movements.

Venezuela announces amnesty bill that could lead to release of political prisoners

Venezuela's acting President Delcy Rodríguez on Friday announced an amnesty bill that could lead to the release of hundreds of prisoners detained for political reasons.

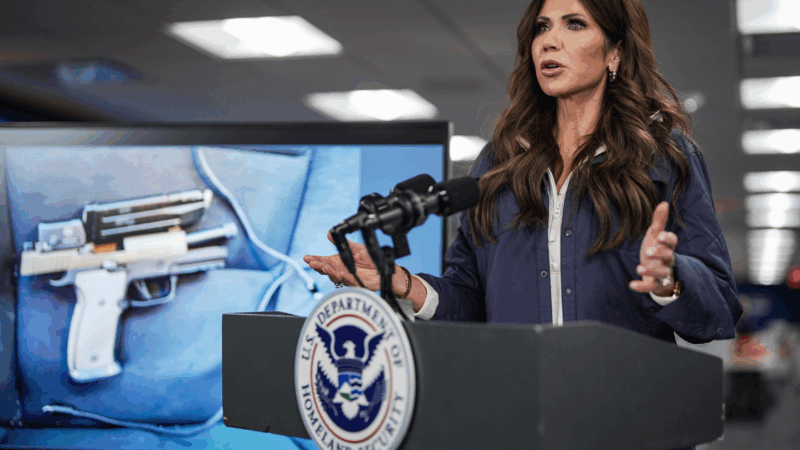

DHS keeps making false claims about people. It’s part of a broader pattern

Trump administration officials have falsely linked Alex Pretti and Renee Macklin Good to domestic terrorism. It's part of a larger pattern by the Department of Homeland Security.

Birmingham faith leaders lead community in vigil in response to ICE actions in Minnesota

Members of the Birmingham community bore the cold Friday evening in a two-hour vigil in honor of Alex Pretti, who was shot and killed by federal immigration agents last weekend in Minnesota, and others who have died in incidents involving United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement.