The Labor Force Puzzle

The latest monthly unemployment numbers for Alabama are due out Friday. The state’s unemployment rate is down about 2-percent over the last year. While that seems like good news, there was something in the numbers which caught the attention of WBHM’s Andrew Yeager. And he went looking for an explanation.

We know that Alabama’s unemployment rate has been dropping. But there’s another number that part of calculating the unemployment rate. It’s called the labor force. Officially it’s the number of people with jobs plus the number of unemployed people who looked for work in the last month. It’s as if the labor force is the entire statewide team employers can draw on to build cars, teach in schools or build buildings. But people are leaving the team.

It’s been happening over the last two years. Slowly at first and then it started picking up a year ago. So even though the unemployment rate is getting better in Alabama, almost 70,000 people stopped working or stopped looking for work in the last two years.

It’s been happening over the last two years. Slowly at first and then it started picking up a year ago. So even though the unemployment rate is getting better in Alabama, almost 70,000 people stopped working or stopped looking for work in the last two years.

However, if you look at surrounding states over that same time period, you don’t see that drop. So where are these people going? Sounds like a question for your friendly neighborhood labor economist. This is Sara Helms, an economist at Samford University.

However, if you look at surrounding states over that same time period, you don’t see that drop. So where are these people going? Sounds like a question for your friendly neighborhood labor economist. This is Sara Helms, an economist at Samford University.

“There’s something there that’s a little bit disturbing. That’s not how you want to lower your unemployment rate.”

She says we know recessions can cause people to retire or go back to school. Also unemployed workers become discouraged and just stop looking for work. But we don’t really have good data to figure out specifically what’s driving Alabama.

“All these numbers are calculated on different calendars and by different agencies. We can look at these raw numbers and we can hypothesize about what’s going on [but] it’s actually incredibly difficult to get to the heart of the matter in real time. That’s frustrating as an economist and I’m sure as a reporter.’

Helms hesitates to provide a specific explanation to the fact Alabama is behaving differently from the other southeastern states. She says though it’s important to note the country as a whole saw its labor force plummet in the recession and all the southeast states are in this kind of historically low range. So for Alabama, maybe it has something to do with the state’s immigration law. Although that’s a big maybe. Maybe having the state’s largest county in municipal bankruptcy is dragging things down. But that’s a big maybe.

“I’m a good economist. I have six hands and on the one hand and on the other and on the other.”

So for another hand here’s Ahmad Ijaz, an economist at the University of Alabama.

“It’s because of a combination of different factors.”

He points to the same ideas — retirees, people going back to school and discouraged workers. But again this is from the national picture. Ijaz says maybe people are relocating to other southeastern states and that’s why their labor forces are trending upward, but we won’t know for sure for a couple of years. He does point out states’ economies are structured differently and that affects how the numbers move.

“For example, Florida is very heavy into services type jobs. And services is one of the sectors which is adding jobs. Whereas Alabama has a lot more manufacturing jobs.”

So we’re kind of in a situation where we can see the forest but we can’t see the trees very clearly. What do the people in state government think — the people who talk about bringing jobs to Alabama?

Tom Surtees is director of the Alabama Department of Industrial Relations. He says the shrinking labor force is concerning, but not unexpected. Still he says every Alabamian should have the chance to get a job. And the state is trying to create the opportunity.

“We’re working every day bringing in, working with employers possible employers, existing employers to bring jobs to Alabama. And as jobs come in people will come into the state with them, so we will see a growth in our workforce.”

Surtees says Alabama is coming out of the recession faster than surrounding states and that’s true if you look at the unemployment rate. But he acknowledges that’s not the case if you look at the actual number of people employed or looking for work. So this whole fixation on labor force, does it even matter then if the unemployment rate is dropping.

“Well, you could have an unemployment rate of zero if no one is looking for a job.”

Oakworth Capital Bank economist John Norris says a shrinking labor force generally means fewer people earning paychecks.

“That’s ordinarily not in the recipe for vibrant economic growth. [And] That’s a real problem. Yes, it’s great the unemployment rate has fallen but at the same time we want to make sure the number of employed keeps on going up and right now we’re not really seeing that.”

The number of employed…a new number to puzzle over.

How George Wallace and Bull Connor set the stage for Alabama’s sky-high electric rates

After his notorious stand in the schoolhouse door, Wallace needed a new target. He found it in Alabama Power.

FIFA president defends World Cup ticket prices, saying demand is hitting records

The FIFA President addressed outrage over ticket prices for the World Cup by pointing to record demand and reiterating that most of the proceeds will help support soccer around the world.

From chess to a medical mystery: Great global reads from 2025 you may have missed

We published hundreds of stories on global health and development each year. Some are ... alas ... a bit underappreciated by readers. We've asked our staff for their favorite overlooked posts of 2025.

The U.S. offers Ukraine a 15-year security guarantee for now, Zelenskyy says

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Monday the United States is offering his country security guarantees for a period of 15 years as part of a proposed peace plan.

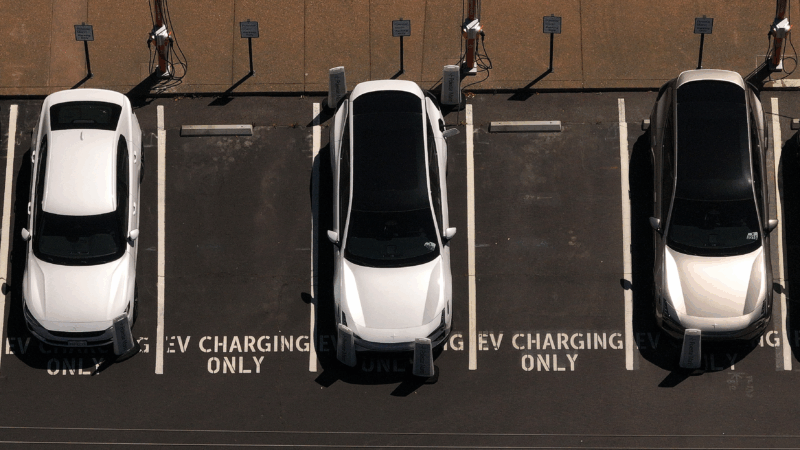

Electric vehicles had a bumpy road in 2025 — and one pleasant surprise

A suite of pro-EV federal policies have been reversed. Well-known vehicles have been discontinued. Sales plummeted. But interest is holding steady.

A ‘very aesthetic person,’ President Trump says being a builder is his second job

President Trump was a builder before he took office, but he has continued it as a hobby in the White House.