State Board Approves B’ham Schools Management Plan

It didn’t take much convincing for Alabama schools chief Tommy Bice to secure his board’s formal

approval of the management plan he’s putting in place for Birmingham Schools. State board members,

after expressing appreciation for Bice’s handling of a difficult situation, voted unanimously to approve it

at a special called meeting early Thursday afternoon.

Bice was required to come back and get that approval per the state board’s June 14 resolution, which gave Bice

authority to take control of Birmingham City Schools (BCS) if the local board didn’t implement cost cuts by its

meeting this past Tuesday night. The local board didn’t approve those cuts, triggering state’s outright

takeover of the Birmingham system’s purse strings the next morning.

The management plan, which now accounts for the top of BCS’s organizational flow chart, has three components. The first is the assignment of a CFO, which has already happened: former state superintendent

and current investigation leader Dr. Ed Richardson will assume that role

and report directly to Bice.

“He and the team have been there since April … so they already know, intricately, the

financial workings of that system,” Bice told the state board.

The second aspect involves the particulars of how state officials will work with the local board and local

administrators for the duration of the state intervention, which will likely last more than two years. Bice

said he hopes for as much cooperation as possible. But that extends only to a certain point.

“This can be as collaborative as anybody wants it to be,” he said. “… But I reserve the full authority

under state law to take action…. At some point, somebody’s got to make a decision. And at this point —

and I’m not into authority, but I actually have it under state [law] — and it’s time that some decisions

be made.”

The local board will still meet and take votes, but on matters directly or indirectly related to finance, the

state — meaning Richardson, who reports to Bice — will have final say. Put another way, the local board

can commend people or bestow awards and recognition, but other than that, it has very little real power.

The third part of Bice’s management plan as presented to his board was a clear statement of its

overarching goal — the goal of the state’s involvement in general: to bring the Birmingham system into

“compliance with financial and legal mandates applicable to all boards of education,” Bice said, adding that the state has no other agenda, and, “We’re not singling Birmingham out.”

Birmingham Schools have only $2 million of the $17 million required by a state law mandating a reserve

of one month’s operating expenses. And that’s without factoring in a $6 million loss in state funding due

to an 800-student enrollment drop (which makes personnel cuts that much more appropriate, said Bice).

The local board missed a May 1 deadline to submit a detailed corrective plan to the state.

Richardson will work with Birmingham’s Superintendent Craig Witherspoon and CFO Arthur Watts —

both of whom are staying on, though they’re reporting to new superiors — to come up with a plan to

restore the district to sound financial condition, Bice said.

But the $12.3-million cost-cutting plan that was the subject of such battles on

the local board will, now that the state is crafting it with little input from that board, likely grow into

a $13.5-million plan. At its July 17th meeting, the local board can either vote it in, or choose

not to adopt it, at which point the state’s administration team would override their vote and enact it

anyway.

Bice acknowledged the pain caused by any personnel cuts, and that many of the problems currently

faced by the local board were inherited. He also described some of the cost-cutting hurdles in the

Birmingham system. One of those is a policy unique to the district: as an employee is demoted, that

employee keeps his or her current salary for one year. In other words, if a six-figure administrator is demoted to a teacher’s aide, that person would keep the

six-figure salary for a full year. So the savings from certain personnel moves — all the more necessary in

Birmingham, which has more than six times as many administrators per student than nearby Shelby

County — will take two years to show up.

Bice and Richardson have implored the local board to rescind that

policy and will likely do so now, but that won’t take effect before the first round of cuts are

made, as the start of the school year rapidly approaches. Add tenure and contract laws and “rollback

policies,” and cutting personnel costs become even more complicated. Birmingham schools will likely

start the school year three days to two weeks later than the original August 20 date.

As part of the cost-cutting plan, the state will “adjust the positions” of 57 Birmingham administrators,

and 42 of them will be moved out of the central office into teaching positions that were already open, said Bice.

“I hope this will be the last time I come before you to talk about this,” Bice told the state board. “We

need to get to work in Birmingham. We need to make some decisions about personnel, school starts … I

can’t imagine that we can get principals hired and have faculties assigned. Nothing’s ready for school to

start, as it could be, if some of the decisions had been made three months ago.”

As of this writing, Birmingham Board President Edward Maddox could not be reached for comment.

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

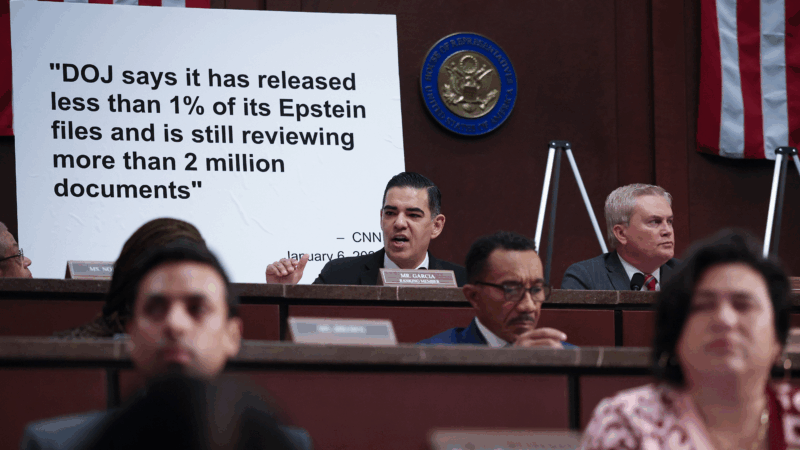

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.