Fight Continues over Shepherd Bend Mine

The Birmingham area has a long, intertwined history with coal. Coal fueled the steel plants which built the city. Coal mines still dot the Alabama landscape. But a planned strip mine along the Black Warrior River in Walker County has generated strong public opposition. WBHM intern Shelby Mauck has this look at the long simmering controversy over the Shepherd Bend Mine.

Gary Hosmer is not thrilled at having a strip mine in his neighborhood.

“The noise, the dust, the blasting…”

Hosmer lives near a bend in the Black Warrior River where the Birmingham-based Drummond Company wants to built an almost 1,800 acre strip mine. Hosmer says for those living very close to the Shepherd Bend Mine, life could be dangerous.

“They will have to drive through the middle of the so-called strip pit to be able to get into their home or out of their home.”

The project may disrupt life for those who live near it, but environmentalists say the damage could be felt far beyond. Part of it has to do with the layout of the site. Nelson Brooke is with the environmental group Black Warrior Riverkeeper. He says the mine would discharge waste water just 800 feet from an intake for the Birmingham water system, potentially putting drinking water at risk for 200,000 customers.

The other issue is how the Alabama Department of Environmental Management approved the mining permit almost four years ago. Brooke says parts of the company’s application were missing.

“We pointed out that some very basic pieces of the law were not followed in applying for this permit, such as the part that talks specifically about how they’re going to prevent pollution from harming the river. That plan was not filled out, it was not submitted, yet it was checked off as being part of the application.”

Nelson is also skeptical Drummond or the state will be able to adequately control pollution from the mine. Black Warrior Riverkeeper and other groups have filed lawsuits against the state to block the permit. Bill Andreen teaches law at the University of Alabama, which is involved in the Shepherd Bend case. Speaking for himself, not the UA, Andreen says challenges to this kind of permitting are not uncommon; but, he says, it’s unprecedented for a strip mine to be located so close to a drinking water intake.

“The problem with facilities like this – no real treatment. So there’s just retention ponds and then when it rains really hard, basically everything that’s in the retention ponds or that exceeds the capacity of the retention ponds is discharged.”

While the lawyers slug it out in the classroom, others fight the mine on the streets. Earlier this year about 30 students, NAACP members, and environmentalists marched outside a University of Alabama System Board of Trustees meeting held at UAB. They targeted the board because much of the land for the proposed strip mine is owned by UA. UAB student Joseph Olson organized the protest and came armed with a 6,000 signature petition asking trustees to withhold mineral rights from Drummond Company.

“I’d like to see the Board start actually discussing the issue. I’d really like to see them take a stance on the issue instead of just sitting back and waiting for things to blow over.”

Opponents are also suspicious because Drummond’s CEO is an emeritus trustee for the University. For it’s part, UA says it has no current plans to sell or lease the mineral rights. Drummond declined to comment for this story. The company may not be talking, but backers of such projects generally point to the new jobs they’ll create. Gary Hosmer says the mine may provide good paying jobs, but it’s a short term gain for long term pain.

“Those mines might last five, six, seven years. What a lot of people don’t understand is if they go in there and strip that, after the mine is completed, reclaimed, its got to sit there seven years before you can do anything with it.”

The Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s lawsuit remains on appeal. Which means Drummond will wait longer to find out when, if ever, dirt will turn at the Shepherd Bend Mine.

Epstein files fallout takes down elite figures in Europe, while U.S. reckoning is muted

Unlike in Europe, officials in the U.S. with ties to Epstein have largely held their positions of power.

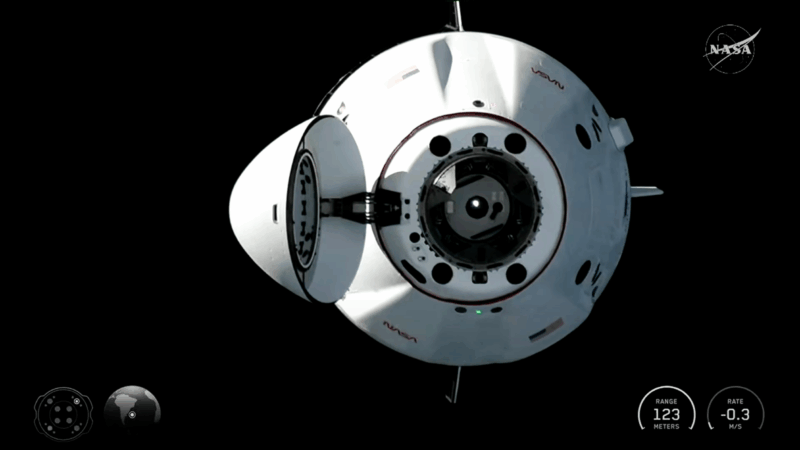

Four people on NASA’S Crew-12 arrive at the International Space Station

The crew will spend the next eight months conducting experiments to prepare for human exploration beyond Earth's orbit.

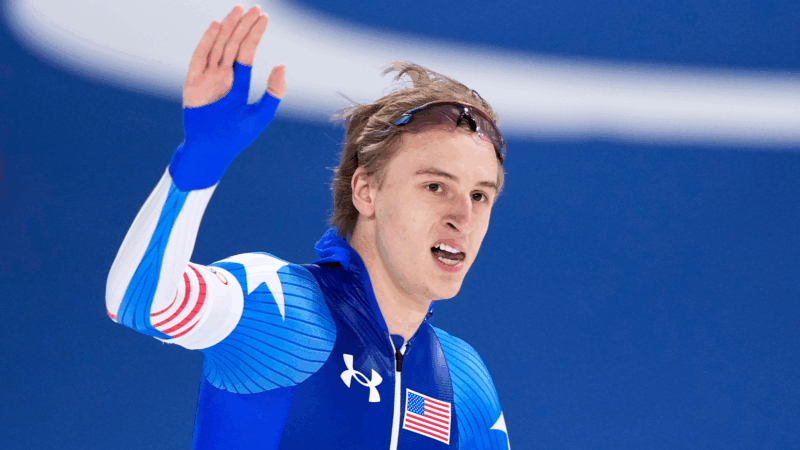

American speedskater Jordan Stolz wins second Olympic gold with 500-meter race victory

With the win, Stolz joins Eric Heiden as the only skaters to take gold in both the 500 and 1,000 at the same Olympics.

US military reports a series of airstrikes against Islamic State targets in Syria

The U.S. military says the strikes were carried out in retaliation of the December ambush that killed two U.S. soldiers and one American civilian interpreter.

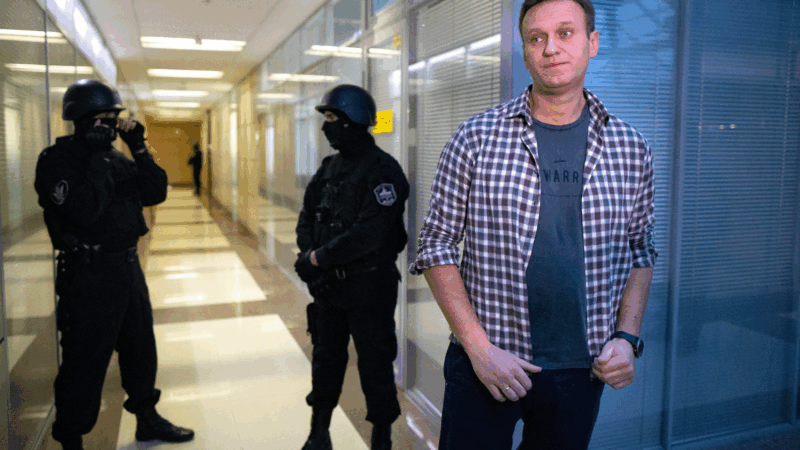

5 European nations say Alexei Navalny was poisoned and blame the Kremlin

In a joint statement, the foreign ministries of the U.K., France, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands say Navalny was poisoned by Russia with a lethal toxin derived from the skin of poison dart frogs.

It’s a dangerous complication of pregnancy — but a new drug holds promise

Researchers celebrate early results of a drug that may become the first treatment for a serious complication of pregnancy called preeclampsia. It's got the potential to save many lives.