Amendment Four: Does It Do More Than Remove Racist Language?

Amendment Four: Removing Racist Language or Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?

When you go to the polls next week you’ll have 11 statewide amendments to vote on. A lot of them may seem confusing, but one should be a no brainer. It would remove from the state constitution racist language mandating school segregation and poll taxes.

To understand Amendment Four we need to step back in time. Alabama adopted its current constitution in 1901. The President of that Constitutional Convention, John B. Knox, stated in his inaugural address that the intention of the convention was “to establish white supremacy in this State”. The document outlawed interracial marriage, instituted poll taxes, and required racially segregated schools. Amendment Four on next week’s ballot would strike down some of that language – specifically, the poll taxes and the segregated schools.

“We always need to update our constitution. I think that’s what this amendment does. It cleans it up,” says Bill Armistead, chairman of the Alabama Republican Party.

He says there’s no reason to keep language like “separate schools shall be provided for white and colored children” because it’s no longer applicable. The state hasn’t enforced that provision since the 1960’s. And the courts ruled it unconstitutional in the 1990’s.

But Critics Say – Wait!

“There’s more to it, in our opinion, than what meets the eye,” says David Stout is with the Alabama Education Association, one of the most vocal critics of Amendment Four.

He says as odd as it seems taking out the segregationist language would be even worse than letting it stand. That’s because AEA attorneys believe the rest of the language the court threw out in the 1990’s ruling would be reinstated, including a line that says “nothing in this Constitution shall be construed as creating or recognizing any right to education or training at public expense.” So basically, Stout says, the state would no longer have a constitutional obligation to provide public education for any students. He says there’s no way Alabama would dismantle its public education system… but, he says, it sends a really bad message.

“How do you think it would sound to an economic developer to say, well in Alabama what we’ve just done is pass a constitutional amendment that denies the state’s responsibility and duty to educate any child?”

The Influence of Special Interests

Amendment Four was originally sponsored by several black lawmakers including Democrats Rodger Smitherman of Birmingham and Vivian Figures of Mobile. But they all voted against sending it to voters because, opponents say, the language was changed along the way by powerful special interests.

David Stout says that’s always a risk when you amend a constitution piece by piece, like Alabama does. He’s an advocate for a constitutional convention that would rewrite the whole document in one – public — swoop. But GOP chairman Bill Armistead says not so fast. “How do you determine who the delegates are going to be to the convention? And it can be very much supported by special interest. Whereas if you take article by article and put it before the people of Alabama and vote it up for down, that’s the cleanest way I think of updating our constitution.”

When Republicans took control of the state legislature in 2010, they set up a Constitutional Revision Commission charged with rewriting the state’s constitution article by article. Commission Vice-Chair, Rep. Paul DeMarco of Homewood says he’s not discouraged by the controversy around Amendment Four. He says “it’s never been easy and it won’t be easy, but that’s okay. That’s part of the process.”

You can find a summary of all of next week’s ballot amendments here.

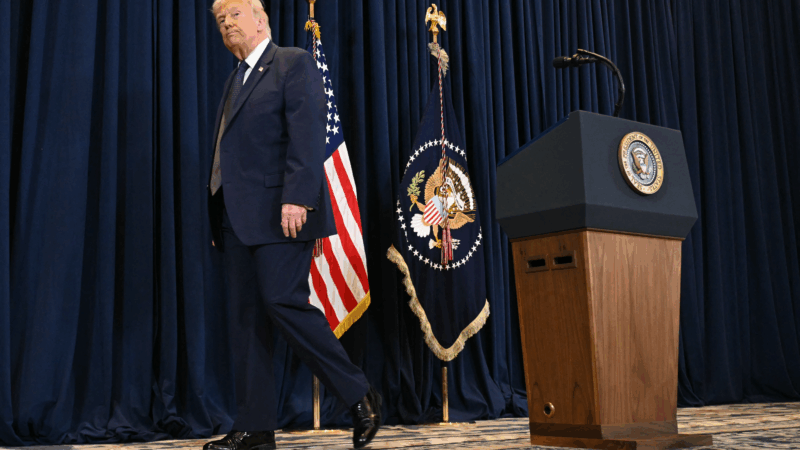

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Bam Adebayo’s 83-point night was one to remember. But not everyone was pleased

Detractors point to Adebayo's one-of-a-kind stat line — 43 field goal attempts, 22 3-point attempts and, most of all, NBA records of 36 free throws and 43 attempts — as proof of stat-padding.

Trump says Democrats must cheat to win. What do his supporters think?

NPR spent several days traveling across a pair of swing districts in Pennsylvania to find out. The answers show how much has changed since the 2020 election.

The government is investigating new claims that DOGE misused Social Security data

The fallout from DOGE staffers' efforts to access sensitive Social Security data continues as an agency watchdog disclosed a new investigation into "potential misuse" reported by a whistleblower.