Part 3: Walking School Bus

What has bright colors, traffic signs, dozens of feet, and provides exercise, companionship, and a safe way to school? It’s a new community-oriented health and safety strategy called a walking school bus. In the last of a three-part series on school transportation, Dan Carsen has more from the Southern Education Desk at WBHM:

It’s early morning in Birmingham’s East Lake neighborhood. Robinson Elementary School students and their parents and grandparents begin to meet on a street corner near a small portable sign that says walking school bus stop. The kids look and sound excited; the adults do too. Volunteer Charles Sanford, a large, patient man in a bright yellow safety vest, takes the roll.

Terri Harvill, one of those rare adults whose energy matches that of a large group of children, is the other official “bus driver.” She goes over some hand signals and safety tips.

The day before, Harvill had walked the route — six tenths of a mile — with other “drivers.” They introduced themselves to people they met along the way. Harvill hopes the program takes off and benefits the neighborhood kids:

“Hopefully they’ll find some walking partners, some friendships. And hopefully we’ll even have some natural ‘safe houses,’ where we can identify some people if there’s an emergency — if a child ever has a medical emergency, or they feel unsafe they know that this is a safe place.”

Kids — and adults — are safer when walking in groups. Besides the dangers posed by speeding or inattentive drivers, Harvill points out, “All adults really don’t have good intentions; all children don’t have good intentions. You never know.”

Leetonio Hightower, father of an energetic “bus walker” of the same name, is one of the volunteers. In addition to the health benefits of walking, he says safety is a key reason he’s supporting the program.

“I like the fact that all the kids are going to be walking together, and they will learn safety as far as when to cross the street,” he says. “It’s going to be an awesome thing. It’s all about getting the neighborhood involved.”

The group of seven students, two official “drivers,” and three volunteers from the neighborhood make up one of the four walking school buses going to Robinson Elementary. It’s the inaugural run, and everyone’s fired up. The group moves out, first beeping like cars, then counting loudly in unison to 200. At all street crossings, adults step into the intersection first, carrying big “stop” or “slow” signs.

By design, walking school bus programs are shaped by the communities where they operate, and the hope is local people will take them over completely. If the programs work, it’s usually because students, parents, teachers, school administrators, community groups, and government agencies work together. This particular walking school bus, and the ones just starting at Hemphill Elementary and Hudson K-through-8, came about through a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Employees and volunteers from the YMCA, the United Way, and the county health department are taking part.

The technique is popular in England and New Zealand and in a growing number of U.S. cities. Though walking school buses are suited to urban areas and suburbs, they have been used successfully in rural areas, including here in Alabama: Instead of dozens of actual buses and cars converging on a school, students use stops less than a mile from campus, but away from the traffic, noise, and fumes.

Back at Robinson Elementary, Principal Sandra Kindell, who’d driven past a walking bus on her way to work, is outside to greet the walkers when they arrive.

“I’m glad to see this coming back,” says Kindell. “We have so many cars. We never saw this many cars dropping kids off at school when I was a little girl. Everybody walked. And we were much thinner then. We were healthy and we didn’t even know it! We didn’t even realize that was so important. So I’m really excited about it.”

The Alabama Departments of Transportation, Education, and Public Health are encouraging people to take part in International Walk to School Day on October 5th. Officials at those agencies say walking to school is a simple way to fight childhood obesity, improve in-class focus, reduce traffic, and make communities more pedestrian-friendly. Based on reaction to the walking school bus — the smiles from neighbors, the care taken by morning motorists, the youthful energy burned — it seems like an old idea whose time has come again.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

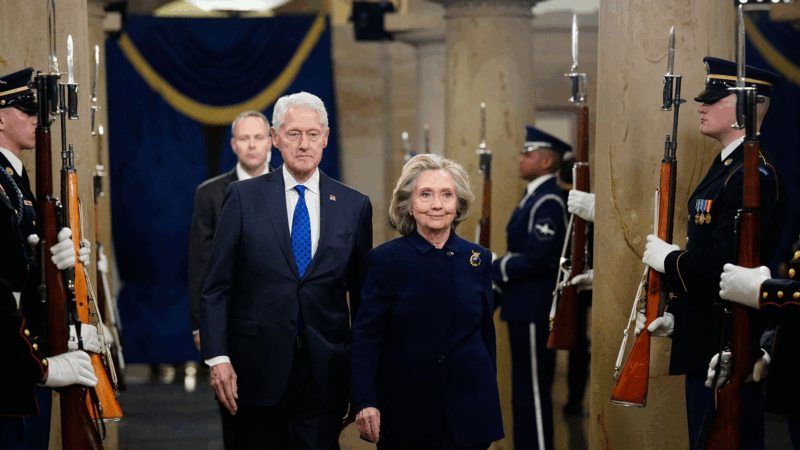

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

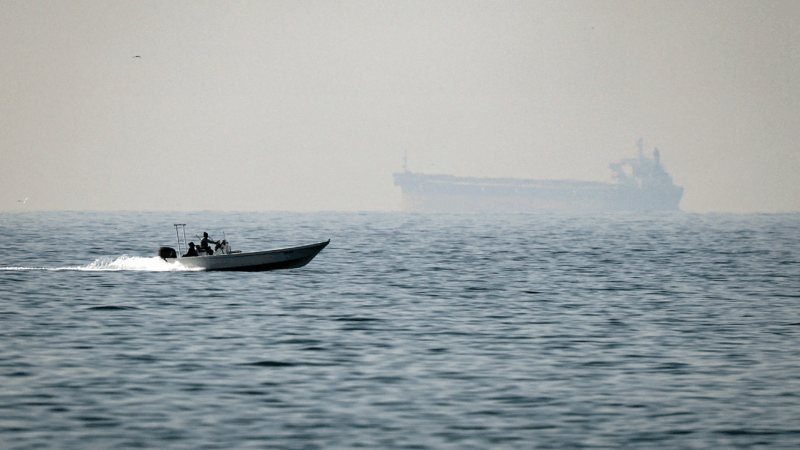

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.