Defibrillators

Depending on the beat, reporters often cover heart-stopping situations. But once in a while, journalists get to write about the opposite.

As of last week, all of Alabama’s public high schools, junior high schools and middle schools have automatic external defibrillators. These heart-restarting devices, often referred to as AEDs, deliver an electric shock that can restore normal heart rhythm. They’re relatively easy to operate: they diagnose the problem, they actually tell users what to do, and the batteries and chest pads have clearly marked expiration dates.

The units cost between $1,000 and $3,000, though the models now in those 1,310 Alabama school buildings are generally closer to the low end of that range. Their presence across the state came about partly through the efforts of three people: Dr. Yung Lau, a professor and associate director of pediatric cardiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB); Barbara Mostella, the department’s pediatric care coordinator and head electrophysiology nurse; and Chris Brown, who runs Alabama LifeStart, a statewide affiliate of

Project Adam.

“We’re very excited about this,” says Dr. Lau. “But now the hard work begins. We have to provide continued training, and make sure people keep up with the maintenance of the batteries and pads … and not only with AEDs, but getting schools to think about and be trained on their emergency procedures, like CPR, in general. This is a good first step as we try to make sure schools are ready to respond to cardiac arrest.”

Lau, described by Brown and others as patient and humble, says he’s “just the mascot” and that Mostella and Brown are “the driving force behind the effort.”

Through repeated news accounts of student cardiac arrests – including but not limited to athletes – and through their daily work, Lau and Mostella came across the heartbreaking results of a lack of defibrillators or the lack of proper training, unit maintenance, and unit accessibility. They also knew of young people being saved by the devices, particularly three Birmingham-area children within a six-month period in 2004 and 2005. Dr. Lau had heard of Project Adam, and while he was meeting with Chris Brown on another matter, the two discussed making that group’s goals a reality in Alabama. They partnered with UAB and Children’s Hospital of Alabama and established Alabama LifeStart.

In 2007, the newly formed group and the state department of education conducted a survey that found 20 public school systems didn’t have a single defibrillator at any of their schools. That translated into 71 high schools and 107 middle schools without the devices, mainly in the state’s Black Belt region.

“Research showed a dramatic, obvious need in Alabama,” said Brown.

“We’re very excited about this, but now the hard work begins.” -UAB pediatric cardiologist Dr. Yung Lau

LifeStart’s education, training, and fundraising efforts then began in earnest. The group got funding from the two hospitals, charities including the Lord Wedgwood Foundation, and corporations including Alabama Power and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama. Schools got AEDs on condition that staff receive training. As of Aug. 9, 2011, all public high schools and middle schools had the units and have had at least one training session.

But as Lau said, the work is not over. Many of the schools – especially the larger ones – could use another defibrillator, but more importantly, students, teachers, and administrators need regular operation and maintenance training. The usual set-up involves making one person per building responsible for making sure, for example, that the batteries are fully charged.

Alabama LifeStart’s efforts also include increasing awareness of sudden cardiac arrest and the importance of prevention and rapid response through in-school educational programs and “leave-behind” materials, training school personnel in CPR and proper AED use, and providing regular follow-up and assessment to ensure that training is ongoing and effective.

Project ADAM began in 1999 after a series of sudden deaths among high school athletes in southeastern Wisconsin. After Adam Lemel, a 17-year-old high school student, collapsed and died while playing basketball, Adam’s parents and a childhood friend of Adam’s collaborated with Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin to create the program in Adam’s memory.

Nationally, some 7,000 high-school-aged students die of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) each year. Though the probability of middle, junior high, or high school students suffering SCA is very low, it’s higher than that of elementary school students. And, there are 1,106 elementary schools in Alabama.

To donate to Alabama LifeStart, contact Dr. Lau at UAB Pediatric Cardiology, 9100 Women and Infant’s Center, 1700 Sixth Ave. South, Birmingham, AL, 35233.

Annual governors’ gathering with White House unraveling after Trump excludes Democrats

An annual meeting of the nation's governors that has long served as a rare bipartisan gathering is unraveling after President Donald Trump excluded Democratic governors from White House events.

Federal judge acknowledges ‘abusive workplace’ in court order

The order did not identify the judge in question but two sources familiar with the process told NPR it is U.S. District Judge Lydia Kay Griggsby, a Biden appointee.

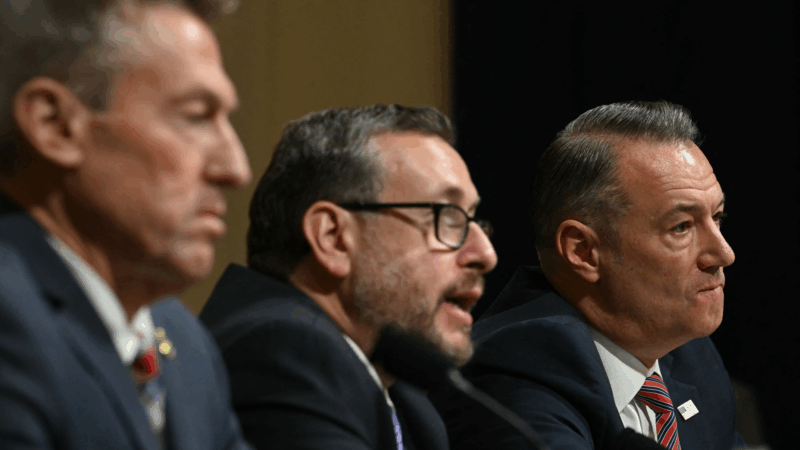

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

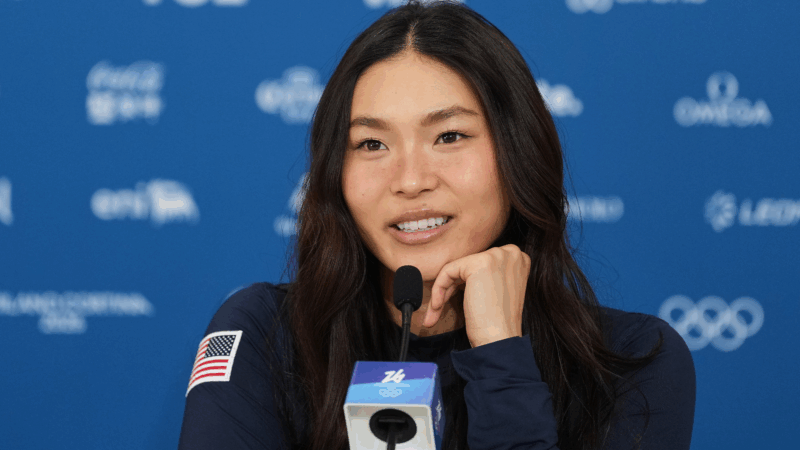

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.