Alabama Organic Agriculture

In the United States, sales of organic food and beverages have grown from $1 billion in 1990 to nearly $25 billion in 2009. There are five million certified organic acres in the U.S.. But you won’t find many in Alabama because, as WBHM’s Tanya Ott reports, a combination of cultural and market forces means this state has the fewest certified organic farms per-capita in the country.

It’s mid-morning in downtown Birmingham and if the sound of crowing roosters surprises you you’ve obviously never been to Jones Valley Urban Farm. It’s three and a half acres nestled between the highway and the Jefferson County Courthouse. Right in the thick of downtown. Edwin Marty is executive director of Jones Valley Urban Farm. He also manages the 25 acre farm at Mt. Laurel in Shelby County.

“We don’t use synthetic pesticides, herbicides or fertilizers to produce our food. We actually go beyond that and try to practice regenerative techniques in everything we do. We capture our rain water. We try to convert all of the resources on the farm back into compost so we’re using as few off-farm inputs as possible.”

What his farms aren’t, though, is certified organic. Alabama has the lowest number of certified organic farms per capita in the country. And by lowest, I mean really low. In 2008 there were just eight certified organic farms in Alabama. One farm for every 600,000 people. By comparison, the next lowest state, Louisiana, had one farm for every 300,000 people. And Vermont, the state with the most certified organics farms per capita? One farm for every 1,100 people.

Experts and farmers say there are many reasons there aren’t as many certified organic farms in Alabama.

“It’s just a hot humid place with soils a little bit more worn out because they’ve been cropped so extensively…”

That’s Karen Wynn. She’s an organic farming consultant who farmed all over the country before settling in Hartselle, Alabama.

“And just the heat and the long growing season breaks down the soil faster. That combined with things like pests having a longer growing season and more time to have more life cycles. I mean we have kudzu and fire ants here.”

Wynn says there’s another, more institutional reason, the state doesn’t have more organic farmers. In the 1970s, 80s and 90’s, organic certification was done on an ad hoc basis by various state and regional organizations. Alabama was one of the only states that didn’t have a certifying agency. So when the USDA established national certification about a decade ago, Alabama was already lagging. And so were extension agents and land grant institutions like Auburn University and Alabama A & M, according to critics. Edwin Marty says when he started Jones Valley Urban Farm ten years ago he was told it would never work.

“I was told point blank by a researcher from one of the land grant institutes that we could not grow food organically in Alabama. We certainly couldn’t grow it organically on an urban farm in the middle of the city.”

“It’s not that it wasn’t taken seriously,” says Joe Kemble, a professor at Auburn and an extension vegetable specialist.

“It’s just that nobody knew if you could really make money at it. It really differed by region, even within in the state, it was just like the jury was out. Nobody could really decide what was good and what was bad about it.”

Kemble says they’ve come a long way. Many of the old guard researchers and extension agents have retired and been replaced by scientists and county agents who understand and appreciate organic farming.

Kemble says the numbers of deceiving, because while there were only eight certified organic farms in Alabama three years ago, there were (and are) many growers who use organic practices but just don’t want to apply for certification either because of the cost or the paperwork or because they don’t really need it. Edwin Marty says Jones Valley Urban Farm is in that camp.

“We’re not certified organic b/c the market for our product is very strong. We don’t have to prove to anybody that we’re farming organically. Our brand name is well-recognized throughout the food community in Birmingham. When we sell to whole foods they have the brand name on products and they’re able to charge the maximum possible amount for that product and therefore they give us back the max they can give any farmer.”

But Jones Valley Urban Farm is a high-profile player, a non-profit that does environmental education and gets a portion of its income from grants and is located in a city with a really strong foodie culture. Some smaller growers in more rural areas don’t have that advantage. Jan Garrett is a research fellow at Auburn University and an organic farmer. She has about 120 acres near Tuskegee, where she grows all kinds of vegetables and berries. She plans to apply for organic certification this summer.

“The advantage for me would be if I sell products in a market that was not dealing directly with customers who know me and know my growing methods. For instance if I had extra tomatoes or carrots and I wanted to take it down to the local earth fair store I could sell it there and if I was certified organic they could label my produce as organic.”

If it’s not USDA certified it would have to be sold as “conventional” at a much lower price.

That price is another sticking point in the organics game. Auburn’s Joe Kemble says one of the reasons organics have never really taken off outside of major metro areas like Birmingham, Huntsville and Mobile is socioeconomic.

“The average income in Alabama is $14,500, which is below the poverty level for most of the country. There’s not a lot of people with that much expendable income to purchase tomatoes. You know when they see the difference in price of 2 to 3 dollars a pound versus 60 cents a pound, they’re not going to make a distinction between something organic versus conventional in terms of some benefit to themselves.”

Still, Edwin Marty thinks there’s a huge untapped market.

“In California the organic farming business is a billion dollar industry. Billion with a B. This is not a small scale thing. This is a huge industry. Why would the land grant institutions in Alabama not be chomping at the bit to support in every way possible the transition of farmers to sustainable techniques to take advantage of these markets is beyond me.”

Some observers say it may be because consumers have lost their taste for organics. Public opinion polling suggests that if they have to make a choice, Americans are now more apt to pick locally-produced foods over organic foods.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

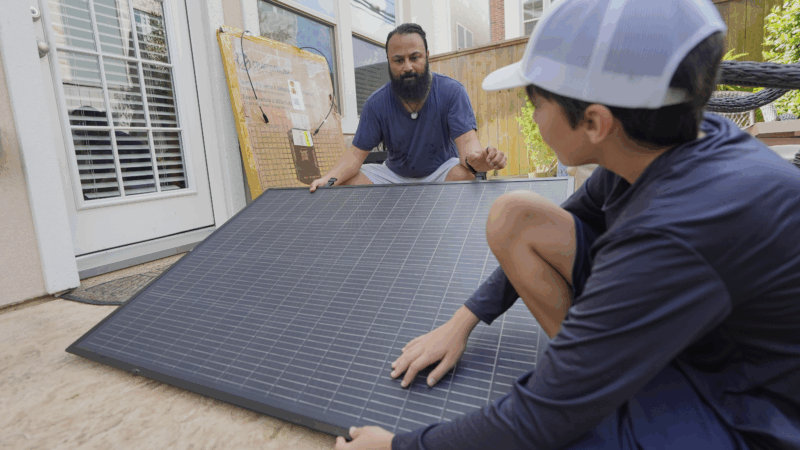

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.