Alabama and the Oil Spill: Marketing Seafood

It’s been almost a year since millions of barrels of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico. If you’re still a little leery about eating seafood from the gulf, you’re not alone. One study found about 70% of consumers nationwide are concerned about seafood safety. Almost a quarter have reduced how much they eat. Alabama’s seafood industry says the catch has been tested and is safe. But as WBHM’s Andrew Yeager reports getting that message out isn’t easy.

Chris Nelson knows the seafood industry. He’s vice president of Bon Secour Fisheries. He’s the fourth generation of this family owned operation. Here at the plant in Bon Secour, Alabama, oysters come off trucks, 100 pound sacks at a time.

“We would dump ’em out of this sack through this process washer here, washes that mud and grit off the outside of the oyster.”

The washed oysters tumble along a conveyor belt and drop into boxes for shipping.

Nelson says the company’s oyster sales are down about 60% from before the spill. Shrimp sales still down by half. A turnaround depends on people buying seafood again. Those people may have visions of oil drenched sea life.

“The overall consumer perception of our products is apparently far worse than we ever thought it might be and it has been longer lasting.”

The Alabama Seafood Marketing Commission hopes to change that. Governor Robert Bentley created this new board in March. It was one of many recommendations to come from a coastal recovery commission prompted by the oil spill. We’ll get back to this new office in a moment, but first, convincing a skeptical public of seafood safety takes strategy.

“They should always put the public safety and health first. Otherwise it’ll create backfire.”

Sora Kim is a public relations professor at the University of Florida. She says gulf coast seafood marketers need to offer information to reduce uncertainty. And the information must be transparency. So don’t just cite government regulators giving the “all clear.” Show how the seafood was tested. Show how it’s been determined to be safe. Above all, don’t stage a media stunt.

Kim points to former British Agriculture Minister John Gummer. At the height of fears over mad cow disease in 1990, Gummer publicly ate hamburgers with his 4-year-old daughter. Except those half eaten hamburgers in photographs were actually bitten by a staffer. Kim says Gummer was criticized not just for staging the event, but some thought he put his daughter at risk.

“So the problem was people were not ready for accepting that beef was safe to eat at the time.”

But let’s say we’ve got that credible and transparent message and a receptive public. You’ve still got to get that message out.

Alabama does have an existing seafood promotion organization, albeit very small if you’re thinking of a “Beef, It’s What’s for Dinner” kind of marketing. The Eat Wild Alabama Shrimp campaign has just two full-time employees. Staff and volunteers mostly market shrimp through cooking demonstrations at festivals around the state. The campaign is limited too because it’s industry funded. So when shrimpers’ pocketbooks suffer, the campaign does too.

Drift down to Louisiana and it’s a far different story.

“My name is Ewell Smith.”

He’s the executive director of the Louisiana Seafood Promotion and Marketing Board. That state started the office in 1984. It runs on a one million dollar budget between state and federal monies. Although the office will have 30 million dollars over the next three years from BP. Smith says the oil spill is somewhat familiar territory because seafood sales plummeted after Katrina, Rita and other hurricanes.

“A month following Katrina we got a clean bill of health from EPA, FDA and NOAA on our seafood and our water. But it took us about two years to turn that around.”

Besides a timeline of years for recovery, Bon Secour Fisheries Vice President Chris Nelson makes the point, just what is Alabama seafood?

“If I’ve got a boat that is delivering shrimp for me and it’s home ported out of Louisiana and he catches shrimp off of Texas and he lands them here in Alabama, then where are those shrimp from.”

What’s needed, Nelson says, is a regional campaign. The seeds of that are in the Gulf Seafood Marketing Coalition. The organization just started last month, backed with federal money. It’s tasked with coordinating seafood marketing between the five gulf coast states, the industry, restaurants and retailers. A former member of Florida’s seafood promotion office is leading the coalition, but no specific plans yet.

So turning back to the Alabama Seafood Marketing Commission, it’s in a similar position. The governor created the organization, but no board members yet. No specific plans. But it does mean this; as a post-spill, regional marketing effort kicks off, Alabama now has a direct way to be at the table.

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

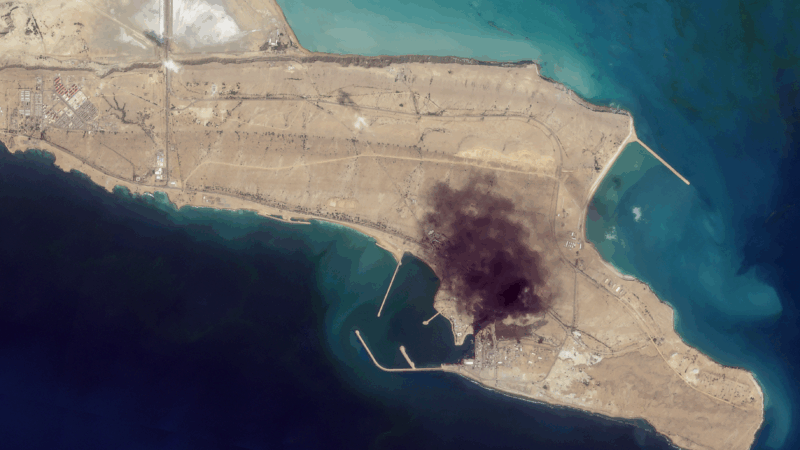

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.