Children’s Mental Health: the Juvenile Justice System

Each year thousands of teens across the country find themselves in jail. For some, their only “crime” is they suffer from a mental illness. Well-meaning parents who are at the end of their rope are convinced the juvenile justice system is one place their teens will get treatment. But as Les Lovoy reports in the first of a two part series on children’s mental health, it doesn’t always work out that way.

Brian and Jennifer Horton live in a quiet neighborhood in Trussville. Most nights, they have family dinner, then some quality time with their two kids who still live at home. Things have not always been this calm. They have a son, Justin. As early as 12, Justin showed signs of a serious mental illness.

“One night we heard a noise upstairs and went up to find out what was going on. And we saw him with one foot out of the house on the roof and another foot in the house, and in his hand was a match that was lit, that he was about to drop onto the floor, and I guess burn the house down.”

The Horton’s got Justin some help in a private counseling center until the money ran out and insurance benefits ended. They say Alabama state agencies were no help. Finally, someone in the state system suggested getting Justin into the Department of Youth Services, or DYS, to get the mental health treatment he needed. So they did. Eventually, Justin was diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder. For years he was shuffled from one juvenile detention facility to another. His parents say his mental illness becoming more pronounced with every move. He’s in his early 20s now, serving time in a Georgia prison for committing a serious crime.

Justin is not alone. A report from the General Accounting Office notes, across the country, families have placed nearly 13,000 children in juvenile justice or child welfare systems to receive mental health treatment. 2/3 of juvenile detention facilities report they incarcerate youth with mental illnesses because there are no other options. Robyn Lawson is a mental health coordinator for Jefferson County Family Court. She says some parents even goad their children to break the law to get them in jail.

“I have had some situations where charges have been filed where I feel like the parents have maybe baited the child in some form or fashion. There’s domestic violence charges, harassment charges, third degree assaults, some minor things to where something has happened, the mom will call the police and go, “He hit me,” you know, “I want him arrested.”

More common, though, is the CHINS petition. That’s what the Horton’s did with Justin.

“CHINS stands for Child in Need of Supervision.”

Nancy Anderson is a staff attorney for the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program, or ADAP.

“It’s a petition that is brought before the juvenile court when a child is for instance is truant from school, when he is essentially not listening to his parents. What you might have called in the olden days, an incorrigible child.”

If the court and the family accept the CHINS petition, the child is on probation. He or she must follow rules laid down by the court. Don’t drink. Don’t stay out after curfew. Meet with your probation officer. These are all what lawyers call “status offenses”. They wouldn’t be criminal if committed by an adult. But if a child breaks the rules, and the parent reports it to the court, the child is often sentenced to a juvenile detention facility.

Currently, there are about 300 kids in custody in Alabama because they’ve violated CHINS petitions. Advocates say prison is no place for these kids, especially those with mental illnesses. They often gravitate to the worst elements in the facilities, as Brian Horton saw with his son Justin.

“After a couple of years in the juvenile system, he knew exactly how to commit crimes. He knew exactly where to get drugs. He knew exactly how to make stuff. He knew exactly what to do and the people to see to get these sorts of things into his life.”

Child advocates also allege that children in Alabama’s juvenile justice system receive subpar or no mental health treatment, at all. But Alesia Allen disagrees. She’s the treatment coordinator for the state Department of Youth Services. She says when a child enters DYS, he’s thoroughly evaluated by licensed professionals. After he settles into the facility, he’s assigned a master level case manager who has constant access to psychologists and psychiatrists. These teams make sure a child takes their meds and attends therapy sessions. But even that, says Allen, doesn’t guarantee a child with mental illness will improve.

“When you get involved in the juvenile system it can snowball so quickly. That you turn around, what I hear parents saying over the years is that’s not what I intended to happen. That’s not what I thought would happen. I didn’t want all of this to happen.”

Part of the problem, say parents and children’s advocates, is that it’s hard to get help from the state. Kids are often passed from one state agency to another with little coordination of care. Again, Nancy Anderson of ADAP.

“And, the child ends up getting lost in between. The family ends up getting lost in between different service delivery systems.

“There is no tracking system. The data systems that each state agency has, that they operate on different.”

Steven Lafraneure is the director of Child Services for the Alabama Department of Mental Health.

“And, so we do not have a common identifier of a child that is in DHR, who somehow I can plug into the system, and also monitor that child while they are receiving DHR services or vice versa. That’s just doesn’t exist. But, I gotta tell ya, that conversation comes up every two or three years.”

Child advocates hope the Alabama Juvenile Justice Act of 2008 will help end the practice of placing kids in jail to access mental health treatment. The law went into effect last October. It states a child cannot be incarcerated for more than 72 hours during a six-month period for committing a status offense. Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb was instrumental in getting the bill passed. She says the bill makes it more difficult for parents to go around the system.

“What we have got to do is create the treatment alternatives at home so those parents don’t have to reach the end of their rope.”

Brian Huff agrees. He’s the presiding judge for Jefferson County Family Court. He admits some kids need to be in jail.

“But most of the children we see here in Family Court do not need to be. They need direction. They need parental role models and they need positive support.”

Back in their Trussville living room, Brian Horton, looks down, grabs his wife’s hand, and takes a breath. Tears well in his eyes as he thinks about their son Justin.

“I just miss him. I miss what we could have had. He’s not there every night. He’s not with me. He’s not, you know. He didn’t have me in his life in a way I wanted to be. So, he can take everything in life that he’s learned and turn it around for himself. I hope that it’s not too late for him.”

Alabama seek to bring back death penalty for child rape convictions

Alabama approved legislation Thursday to add rape and sexual torture of a child under 12 to the narrow list of crimes that could draw a death sentence.

What a crowded congressional primary in N.J. says about the state of Democrats

The contest is one of the first congressional primaries of the year where we will find out what issues are currently resonating with some Democratic voters. Here are some key things to know.

At NOCHI, students learn the art of making a Mardi Gras-worthy king cake

With Carnival in full swing, the New Orleans culinary school gave its students a crash course — and a rite of passage — in baking their first king cake.

The Winter Olympics in Italy were meant to be sustainable. Are they?

Italy's Winter Olympics promised sustainability. But in Cortina, environmentalists warn the Games could scar these mountains for decades.

Their film was shot in secret and smuggled out of Iran. It won an award at Sundance

Between war, protests and government crackdowns, the filmmakers raced to finish and smuggle their portrait of Tehran's underground arts scene to the prestigious film festival.

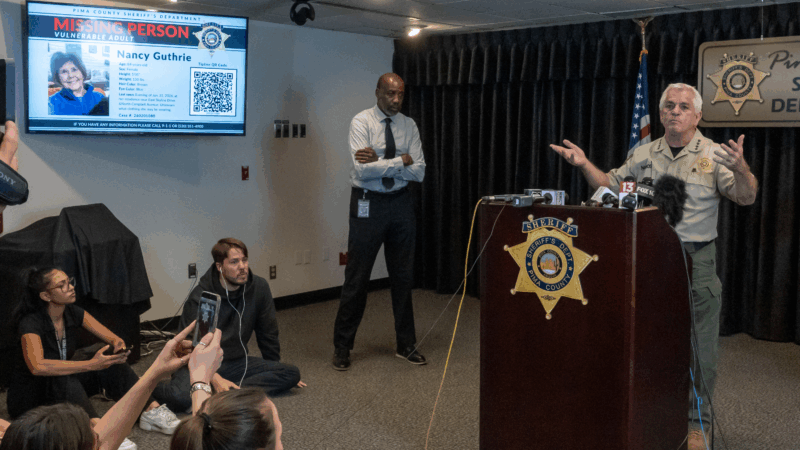

Day 5 of search for Nancy Guthrie: ‘We still believe Nancy is still out there’

The FBI is offering a reward of up to $50,000 for information leading to the recovery of Guthrie and/or the arrest and conviction of anyone involved in her disappearance.