What’s the Deal: Whistleblowers

The movie The Informant took second place at the box office over the weekend. It’s the story of a corporate whistleblower who works with federal investigators to take down an agriculture price fixing scheme. The movie is a real case turned into a dark comedy, but off screen whistleblowers are a serious tool for law enforcement when it comes to investigating corruption. There are laws designed to protect whistleblowers and thus encourage them to come forward. As we continue our weeklong series looking at corruption in Alabama, WBHM’s Andrew Yeager examines if such protections, may be overblown.

Something didn’t seem quite right to Monte Handley. He was an accountant with 20 years in Medicare cost reporting. One of his firm’s clients was a husband and wife team in Shelby County named Marie and Bill King. The King’s business performed audits for area nursing homes.

“Well right away when I started working for them I noticed that the amount of their cost report seemed excessively high.”

So Handley looked at Medicare numbers his accounting firm had provided the government as part of an audit. He questioned the methodology behind those numbers. But the response from the company higher ups seemed vague to him. So he kept investigating, asking questions and not getting answers that satisfied him. Then one day, as they were moving files from the King’s operation to the accounting firm.

“I actually walked in and Marie King was actually cutting a pasting a physician’s signature.”

Handley says he then pulled some previous documents that had been submitted to Medicare and found each signature a perfect match. At this point it seemed, the Kings were submitting reimbursement claims for work not actually performed. Handley says he was convinced this was fraud and took the evidence to his firm’s partners.

“Basically, I was told by them, you know, to continue with the practice or there was the door.”

Handley refused and was fired. He hired an attorney who used a federal statute, the False Claims Act, to purse the fraud.

University of Alabama Law Professor Pam Bucy says the law does a couple of things. First, it allows the government to join forces with the whistleblower to pursue the case. It also lets the whistleblower to seek damages for retaliation, such as being fired.

Bucy says the federal government has offered states incentives to pass their own versions of the False Claims Act. It they did, Washington would provide rebates on Medicaid spending. She says more than 20 states passed such laws but not Alabama. As far as Bucy can tell, there’s no momentum here for it either. She says passing a law would not just mean more money for Alabama, it would be a valuable tool to fight corruption.

“It’s very, very difficult to find out about. And it’s very, very difficult to investigate because it’s usual deep within an organization and it’s usually pretty complicated. And realistically you’re just not going to find out about it and you’re not going to be able to prove it without a whistleblower.”

In the case of Monte Handley, his action led to jail time for Bill and Marie King. This August, they were ordered to pay nearly $1.5 million for Medicare fraud. Handley was awarded 19% of that, but says he’s yet to see any of the money. And getting fired and subsequent involvement in a whistleblower case has taken its toll.

“Well basically, I’ve had to start my career all over again. I’m at a much lower level paying position. I’m making a fraction of what I used to make. It’s actually been very hard on me.”

A wrongful termination suit against the accounting firm Handley formerly worked for is still pending.

Patricia Harned says it’s those negative aspects of whistleblowing which may stop people from going forward. She’s President of the Washington D.C.-based, non-profit Ethics Resource Center. The organization surveys business and government on a range of ethics issues. They looked at anonymous whistleblower hotlines and found in 2007 only three percent of government employees used them. Employees were far more likely to report conduct to supervisors.

“I think the reason people go to someone they know is that it’s easier to have some idea about what will happen with the report than if you use an anonymous help line.”

Harned says she doesn’t believe stronger whistleblower laws will make much difference. She says organizational culture is more influential. Does the workplace prize ethical behavior? Are those who do raise concerns supported?

“And you can’t legislate organizational culture.”

University of Alabama Law Professor Pam Bucy says while they’re not a panacea and they shouldn’t be used frivolously, whistleblower laws do change behavior. She points out when it comes to white collar crime, potential defendants read the news. They remember Enron and other corporate scandals and think…

“Is this going to be worth it to me to take this risk? Oh, it may not because I might get found out by a whistleblower and I might go to prison.”

Bucy also believes such laws are changing the perception of whistleblowers, that they are increasingly seen as heroes and not snitches.

Monte Handley says he has no regrets.

“This was wrong. It was fraud. And it was against the United States of America. It was against the taxpayers. I felt strongly about that. Regardless of the consequences that I’ve been through, I know I’ve done the right thing.”

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

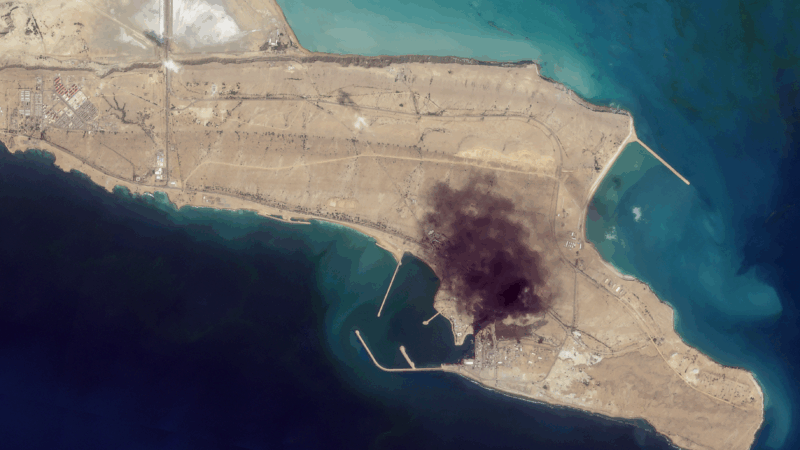

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.