What’s The Deal: Ethics Commission

Ethics is something that usually comes from within, but sometimes public officials need a little outside coercion to keep their ethics in check. For nearly 40 years, the Alabama Ethics Commission has worked to keep state employees and elected officials honest. As we begin a week of reports on corruption in Alabama, WBHM’s Bradley George examines some of the challenges facing the commission and some of the proposal for ethics reform.

It’s the most famous burglary in American history. The Watergate scandal sunk the presidency of Richard Nixon, and forced governments around the country to take a hard look at ethical conduct among elected officials

‘We were among the first states after Watergate to pass ethics reform.’

Jim Sumner is executive director of Alabama’s Ethics Commission. He says the state House and Senate were locked in fierce battle to pass tough ethics legislation, with the secret hope Governor George Wallace wouldn’t sign it. But Wallace signed the bill anyway.

‘Not only were we one the first states out of the chute. But we did, because of this competition, pass an extremely tough law.’

A New York Times article from 1974 called Alabama’s ethics law one of the toughest and most controversial laws of its kind. State officials had to submit financial information not only about themselves but close relatives. Journalists who covered state government had to register with the Ethics Commission. The courts later softened some of those provisions, but Sumner says in 1995 the legislature got tough again.

‘They put in a whistle blower protection. They put in a revolving door provision to prevent people from leaving public office and becoming a lobbyist for two years. They did a number of things like that.’

But there are still holes–big ones–critics say. For instance, a lobbyist can spend up to 250 dollars a day on a legislator without reporting it. Jim Sumner says it’s the most liberal allowance of any ethics law in the country.And the Alabama Ethics Commission is the only one in the US without the power to subpoena witnesses, bank accounts, phone records, and other documents.

‘You’re really tying both their hands behind their backs and then asking them go out and over see potential public corruption. How can they do that if they can’t subpoena records?’

Alabaster state representative Cam Ward introduced a bill this year that would have granted subpoena power to the commission. The bill passed in committee but died when in the full House. Ward says many of his legislative colleagues are reluctant to give the Ethics Commission more power.

‘There are people who resent its creation to begin with and there are those who feel like on the other side who make legitimate arguments that perhaps the district attorney’s office or the Attorney General’s office conducting those investigations.’

So, the Ethics Commission has to wait for the legislature to grant subpoena power.

Indeed, talk of reforming ethics law–from subpoenas to tougher rules on lobbyists–slips from the tongues of many politicians, especially during the campaign season. Governor Riley has pushed for comprehensive reform during his time in Montgomery, and several of the candidates who want to succeed him are talking about ethics reform, too. It’s an issue that resonates with voters, especially since the recent indictments of several local and statewide office holders. But than can lead to the impression that ethics laws are written for…

‘People who feel there ought to be a law every time somebody does something unethical.’

G.Calvin Mackenzie is a professor Government at Colby College in Maine. He’s done a lot of research on ethics law–particularly at the federal level. Mackenzie says waiting for election time or an egregious corruption case like Watergate may lead to tough ethics law. But tough may not always be the best law.

‘You can go back. And in fact, I’ve done this in my research and track the sort of genetic pattern and each of these laws and what you find is they almost always follow the most egregious form of excess. It’s a pretty bad way to make law most of the time. You’re making law to deal with the worst case of something when that’s rarely what occurs.’

And, says Peggy Kerns, the new law many not even be necessary. Kerns is with the National Council of State Legislatures’ Center for Ethics and Government.

‘Usually when public officials do something pretty bad and gets everybody to sit up and notice, that’s usually against the law anyway.’

From his office in Downtown Montgomery, Ethics Commission Director Jim Sumner says even though Alabama’s ethics law has been under scrutiny, it still has many of the things that made it so strong at its inception.

‘We have a good foundation to work from. It’s not like we’re behind the curves on this. We would simply be taking what we have and taking it to the next level.’

But to get to that next level, Sumner will need the support of the legislature and possibly a new governor. And the fate of those elected officials lie with the original ethics commission-the voters of Alabama. For WBHM, I’m Bradley George.

Camp Mystic parents from Alabama seek stronger camp regulations

Sarah Marsh of Birmingham, Ala. was one of 27 Camp Mystic campers and counselors swept to their deaths when floodwaters engulfed cabins at the Texas camp on July 4, 2025. Sarah’s parents are urging lawmakers in Alabama and elsewhere to tighten regulations.

Court rebuffs plea from domestic workers for better pay and respect

They're often paid low wages and lack job protections. A petition to the country's supreme court to support their demands did not see success — and they are protesting.

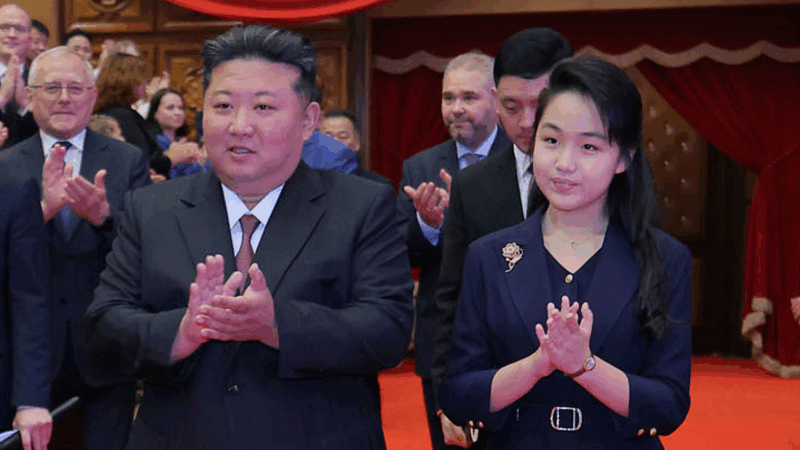

Spy agency says Kim Jong Un’s daughter is close to be North Korea’s future leader

Seoul's assessment comes as North Korea is preparing to hold its biggest political conference later this month, where Kim is expected to outline his major policy goals for the next five years.

Using GLP-1s to maintain a normal weight? There are benefits and risks

Drugs like Zepbound and Wegovy are intended for people who are overweight. Some patients are using them after bariatric surgery to keep pounds from creeping back. Others may just want to lose a few pounds.

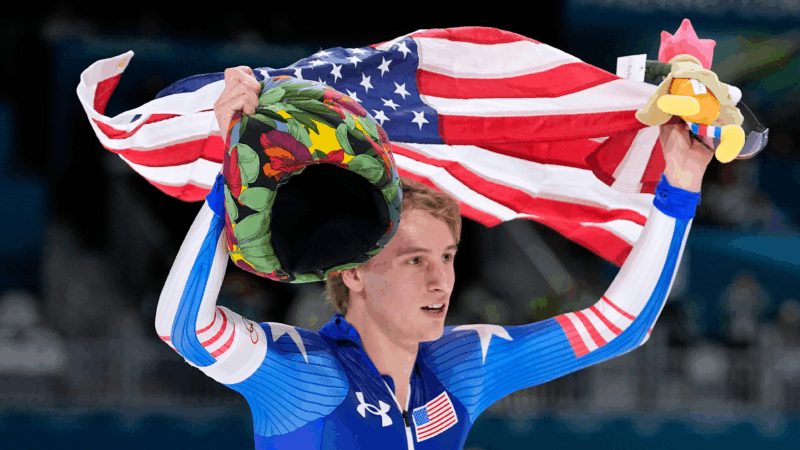

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

How the FBI might have gotten inaccessible camera footage from Nancy Guthrie’s house

Last week, law enforcement said video footage from Nancy Guthrie's doorbell camera was overwritten. But the FBI has since released footage as Guthrie still has not been found.