ASO Bankruptcy Lessons

The situation was not pretty. The ASO owed $2.2 million. Management and musicians were at odds. Patrons were angry from a season cut off prematurely. Current symphony board member Dell Brooke says a number of factors led to the bankruptcy in January 1993.

“In the late 80s the money from the Ford Foundation grant had run out. And there were very big aspirations.”

There wasn’t the money to support the pressure to grow. In short, artistic vision had trumped fiscal responsibility. Birmingham wasn’t alone. A few other orchestras experienced financial troubles in the late 80s and early 90s. The head of the League of American Orchestras, Henry Fogel, says that’s due in part to the business cycle plus simple economics.

“Number one, the decision to buy tickets to go to a concert is a use of discretionary income. If people feel tight economic times, they will do that less often. Number two, the rest of [an] orchestra’s income comes from contributions or income from an orchestra’s endowment. And of course when the stock market goes down the value of the endowment goes down.”

Symphony supporters and community leader Elton Stephens made it their mission to bring back the symphony. Plans were to raise ten million dollars for an endowment and five million for an operating budget. Board member Dell Brooke, who also is Stephens’ daughter, says he basically went out on a daily basis and twisted a lot of arms.

“He had particular people in mind in the community that he thought would be willing to step forward. He was very disappointed that some of the people in Birmingham that he called on were not willing to take a gamble and give money to something that they weren’t sure whether it would be a success or not.”

One of those arms Stephens twisted was Kathy Yarbrough’s, the symphony’s current development director. It was 1995. She worked for the Alabama Shakespeare Festival when she got a call from Stephens.

“I hear you’re the only person in the state that can help me. And I said, ‘Mr. Stephens, that’s so flattering. Thank you.’ He says, “So I want to talk to you. Can you come up to Birmingham and talk to me?'”

So they met and he laid out the fundraising plans. A few weeks later in her mailbox was a letter telling her…

“I had been hired. I’d never been offered the job. It told me when I was starting. What my salary was and everything.”

Still flattered Yarbrough told Stephens she had concerns. He suggested she come back to Birmingham for a luncheon announcing the campaign. At that luncheon he stood up.

“…and with a quiver in his voice he said, ‘I am so proud to introduce to you the first employee of the new Alabama Symphony Orchestra, Kathy Yarbrough.'”

As the fundraising efforts built momentum Stephens asked current mayor of Vestaiva Hills and former UAB President Scotty McCallum to join the effort.

“And we felt there were several things that we needed to do and that was, one, go ahead and put together a program for the symphony for the following year.”

They hired a part-time executive director. They wrote the former members of the symphony.

“and asked them, that we were going to have a new symphony and that, would they be interested? And we got something like 42 replies, ‘yes, we would.'”

McCallum says they were conscious not to overbuild, to stay within budget. That means not planning huge concerts requiring lots of extra musicians beyond the 50 or so they signed. And Henry Fogel with the League of American Orchestras says the number of performances matters too, because concerts cost more than what comes into the box office. To expand, contributed revenue has to make up the difference.

“The wise orchestra figures out how to do that within the constraints of what its community can support and what its own abilities are to raise the revenue to keep it going.”

“In our articles of incorporation we cannot barrow money and we cannot go into debt.”

Symphony Development Director Kathy Yarbrough says those documents are much harder to change than bylaws. So they weren’t just saying, “we’ll keep closer tabs on the checkbook.” They were fundamentally changing the financial rules. If problems creep up, adjustments must be made soon. Today the Alabama Symphony is also among the best endowed organizations in the community, largely because of the work of Elton Stephens.

But let’s take a step back. Actually let’s go to music class. Maybe you remember learning about listening for patterns in music. Themes or motifs which get carried throughout a piece? This might be the most famous.

You hear that pattern throughout Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. But sometimes it can be difficult to catch those themes without seeing the music or hearing the instruments play solo. So let’s take this work that is the Alabama Symphony’s death and rebirth and listen for a few themes. Scotty McCallum?

“Expenditures shouldn’t exceed income.”

Seems pretty clear. Kathy Yarbrough?<?p>

“Thank goodness we’ve got a board that provides incredible leadership.

Okay, fiscal discipline, leadership. Dell Brooke?

“Communication is huge.”

Making sure everyone understands what’s going on. And Henry Fogel?

“We’re not exactly like for-profit corporations. But there are certain practices we can learn from the for profit world.”

Just a few things to consider from a silent chapter in Birmingham’s musical history.

US military used laser to take down Border Protection drone, lawmakers say

The U.S. military used a laser to shoot down a Customs and Border Protection drone, members of Congress said Thursday, and the Federal Aviation Administration responded by closing more airspace near El Paso, Texas.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Pakistan’s defense minister says that there is now ‘open war’ with Afghanistan after latest strikes

Pakistan's defense minister said that his country ran out of "patience" and considers that there is now an "open war" with Afghanistan, after both countries launched strikes following an Afghan cross-border attack.

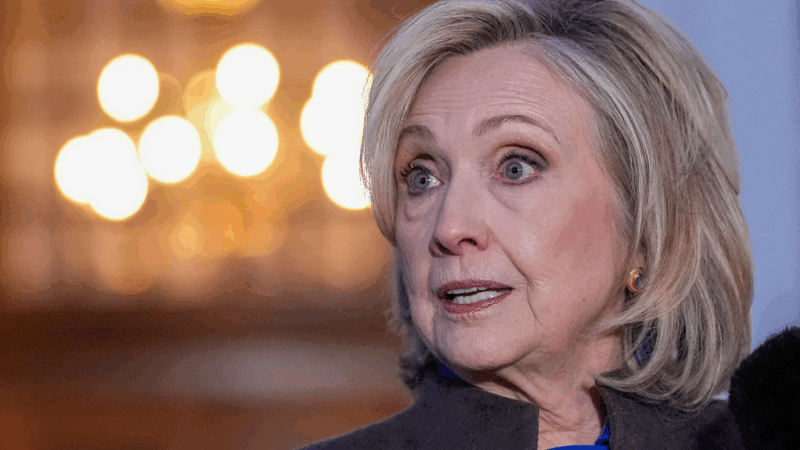

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.