Mental Health Court

About a year ago, Carroll was accused of stealing a floor polisher he rented, a charge he denies. He says the polisher was stolen from him.

And so the justice process began. Police arrested Carroll and charged him with felony theft. But after a routine examination during arraignment, his case started to take a different path.

“I was first told that the judge wanted to evaluate me and see if he could help and it was all for the good of me, and initially I was like, fine, you know. They sent a doctor and some social workers, came over to see me interview me, told them about me the doctor came over and evaluated me, checked prior records, saw where I had been treated for depression before.”

And that’s why authorities offered Carroll a special plea deal. In exchange for waiving a jury trial, he participated in what’s called mental health court. It’s one of three such special courts in Alabama – others are in Jefferson County and Huntsville.

With the exception of a few initial visits with a judge, there’s really not much ‘court’ about it. It’s more a treatment and monitoring program that keeps misdemeanor and non-violent felony defendants with a history of mental illness out of prison.

“Jails have a purpose for certain people. But not all people who commit crimes deserve to be incarcerated.”

Kathleen Champion is clinical director for the Mental Health/Mental Retardation Authority of Jefferson, Blount and St. Clair Counties, or JBS for short.

“It’s a politically-correct statement to say ‘lock people up’ who are committing crimes and make the world a safer place. The problem is that if your jails are overcrowded, the people that you can help and who can change, there’s no purpose in locking someone up because of the fact that basically they were an untreated mentally ill person who has committed a crime.”

Champion says Patrick Carroll was a good fit for mental health court. He had suffered from depression and, at one time, had taken medication. But Carroll was also self-medicating: drinking heavily, often. He’d had other run-ins with the law: mainly for misdemeanor public intoxication.

Had Carroll been convicted on the theft charge in regular court, he could’ve been sentenced to months or even years in prison. And without proper treatment for his depression, without any chance of rehabilitation, he wouldn’t have had the attention, medication and therapy that he received through mental health court.

And that’s true for the thousands of others in the criminal justice system who didn’t have a chance to participate in mental health court.

“They’d be cycling through and if they did get released, they’d go back to the streets.”

Suzanne Muir is project manager for UAB/TASC, which stands for Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities, the group charged with evaluating and overseeing the rehabilitation process through mental health court.

“It’s traditional hands-on case management, as social work was intended to be. Where you have a relationship with your client… and you’re in the community with them.”

Clients get color coded badges. When they’re called – randomly – the client must come in. Either for a drug test, a screening or therapy session. Some days are much busier than others.

On this day, the room is practically empty. It’s what TASC calls a slow color code day. Ironically, a court program is on TV. The clients that are in the waiting room are here to avoid being locked up.

“If you can take people out of that situation and do rehabilitation with them, you’re improving society, you’re helping a human being and you’re saving a lot of money.”

Again, JBS clinical director Kathleen Champion.

“You know, it’s very, very expensive to incarcerate somebody. It’s a lot more expensive than treating them.”

Depending on whom you ask, the savings can be quite significant. According to UAB/TASC, it costs about $54 a day to house an inmate at the Jefferson County Jail. Add in more money for special treatment and/or isolated cells or blocks for the mentally ill and, the cost goes much higher. The fewer the days behind bars, the less the county will have to spend. The more treatment for the inmate, the less likely he or she will be back.

Foster Cook is the director of UAB/TASC.

“What we did with this project was roughly cut the average time for a mentally ill person in the Jefferson County Jail from 89 days to less than 40 days. And the end result -just figure the average days saved multiply that by 54 days plus – we’re saving the county money.”

Tenth Circuit Judge Mac Parsons presides over mental health court in the Bessemer cutoff of Jefferson County. He says he got involved as a tribute to his mother.

“She suffered from severe depression. She was given shock treatments, which was a terrible experience for her. She complained about it terribly, the pain from it. It destroyed parts of her brain and her memory.”

Judge Parsons says his mother was confined to the state mental hospital for a time and he remembers how horrible an experience that was for his family.

But his mother committed no crime. The people he sees have. He says it’s a heavy responsibility to weigh the options for a defendant that comes before his bench… where locking that person up is one of only a few choices in the justice system.

“As a judge, that;s the easiest thing to do… it is… (to send someone to jail?) yeah! I mean, that’s what the public wants from us. You know, we’re a judge to send people to jail. The hard thing to do is to try to change somebody’s life. Till the pill comes along, successes don’t come very often.”

Most people in the criminal justice system are singing the praises of mental health court. But because the program is so new, advocacy groups are keeping a watchful eye. The National Mental Health Association says it’s important to ensure the court doesn’t cause greater criminalization and stigma. And prosecutors and victims’ rights groups say they’re watching to make sure justice is served – and the victim protected — no matter what the offender’s condition or charge. Most of the nation’s 125 mental health courts serve only misdemeanor or non-violent felony offenders. Could violent felonies be next?

“In theory, the victims group does not have an objection to whatever kind of case these courts take on. If it’s done right, the victim will have as much as a measure of justice as other circumstances.

John Stein is director of public affairs of NOVA, or the National Organization for Victim Assistance.

“It probably means the victims’ advocates have to be very wary when mental health court will be taking on violent offenses. I would anticipate that the decision makers over who send them there be looked at with great scrutiny. But, in principle, should they not ever take that on? I don’t think so.”

Other concerns about mental health court include the threat of overcrowding the system -not the penal system, but treatment and monitoring centers. And some legal scholars question whether judges should be playing therapist instead of jurist. Judges are charged in making important decisions about the defendant’s treatment.

But for Bessemer’s mental health court, Patrick Carroll is a success story. One of seven (7) graduates in the past year-and-a-half – and none has been re-arrested. The charges against Carroll were cleared and he paid restitution. He was released from monitoring back in March and says he was lucky to’ve been offered the chance.

“Being accepted in mental health court will help you. No doubt about it.”

It’s his only chance; if he gets arrested again, he’ll face regular court and the prospect of being locked up with everyone else in prison. A place where justice is served, but where the mentally ill may have less of a chance to get help and treatment.

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

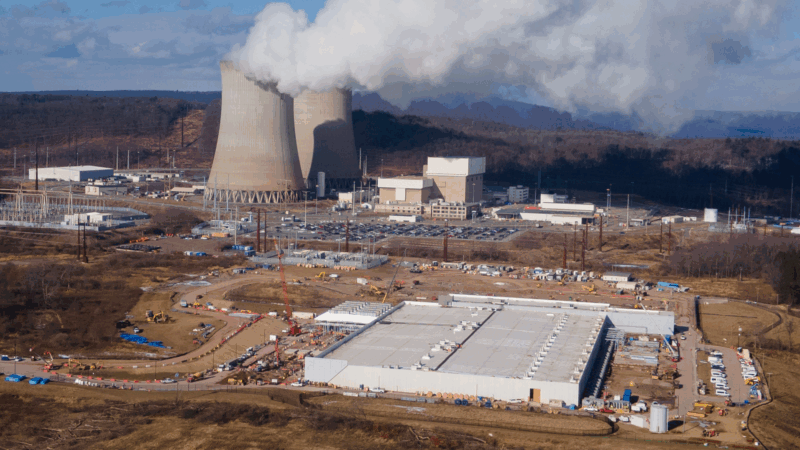

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.

Feds announce $4.1 billion loan for electric power expansion in Alabama

Federal energy officials said the loan will save customers money as the companies undertake a huge expansion driven by demand from computer data centers.

Mortgage rates fall below 6% for the first time in years

The average home loan rate has dropped below 6% for the first time since 2022. Will that help thaw the frozen housing market?

Pentagon shifts toward maintaining ties to Scouting

Months after NPR reported on the Pentagon's efforts to sever ties with Scouting America, efforts to maintain the partnership have new momentum

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Every business wants your review. What’s with the feedback frenzy?

Customers want to read reviews and businesses need reviews to attract customers. But the constant demand for reviews could be creating a feedback backlash, experts say.