Filling The Gaps: The Dental Dilemma

Patel: ‘I’m excited and also kind of nervous because getting out into the real world.’

A world that includes up to $100,000 in debt for many students, including junior Kelli Hill.

Hill: ‘The debt thing’s more’ (laughs) you know, it’s kid of in my face right now! I’ve had to borrow pretty much everything ‘ so I see how much money I owe, I don’t see how much money I’ll make yet.’

Administrators worry that some students are shunning dentistry because of the expense of the schooling, equipment, and establishing a practice. And that, they say, will exacerbate what is already a growing shortage of dentists.

Thornton: ‘I think we’re seeing the tip of a huge iceberg.’

John Thornton is chairman of UAB’s pediatric dentistry program. He says as many as 11 percent of rural residents have never been to a dentist. And the U-S Surgeon General estimates 25-million Americans live in areas lacking adequate dental care services.

Thornton: ‘There’s a big crisis looming around the corner and I think in the next ten years it’s going to hit us and we’re going to be amazed at how severe the shortages are going to be.’

The American Dental Association predicts that 20% of current dentists will retire in the next decade and there won’t be enough new dental graduates to fill those gaps. In the 1970’s and early 80’s the government reimbursed dental schools for every student, but that created too many dentists, so the government stopped the reimbursements. Even if the government were to reinstate that program – few schools could handle more students because there isn’t enough faculty to teach them. UAB dental school assistant dean Steven Filler says that’s because the average private practice dentists makes $150,000 a year. But to teach dentistry, expect to make just $65,000.

Filler: ‘They come out with a lot of debt. It’s easier for them to recoup that debt and to make a better living in a private practice world than it is through dental education.’

Dental school administrators want the federal government to reinstate the reimbursements so they can raise faculty salaries. They also suggest forgiving the loans of dentists who practice in rural and inner-city communities ‘ which are hardest hit by the shortage. Focusing more on the science and prevention could also help, says Richard Neiderman. He’s director of Boston’s Forsyth Center for Evidence-based Dentistry. He says if dentists were versed in the latest research in dentistry ‘ if, for instance, they routinely treated cavities as infections rather than simply drilling and filling ‘ they would increase their efficiency.

Neiderman: ‘Currently, dentists have in their practice about 2,000 patients. Were they to implement evidence-based methods they could have about 5,000 patients in their practice, treating the patients most in need with the intervention and treat the rest of the patients with the prevention’. Double their income and patients would have increased access to care. So it could be a win-win.’

But even if dentists were willing, insurers would need to reassess how they value dentist’s time ‘ making consultation and preventive procedures more lucrative’. An idea some insurers have been slow to embrace.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

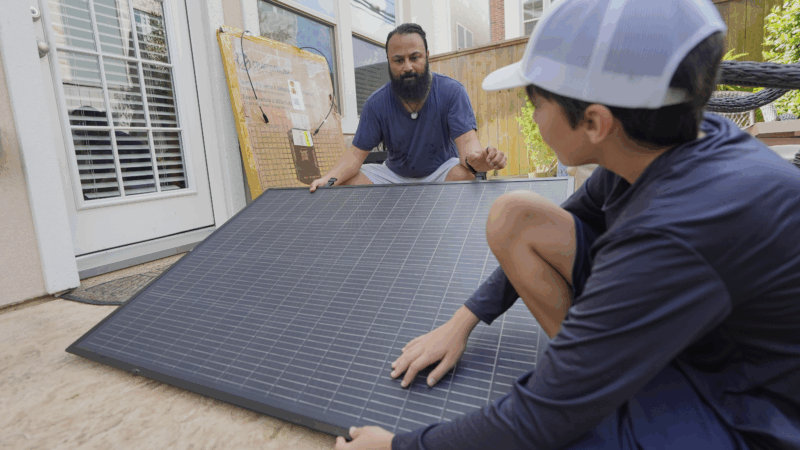

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

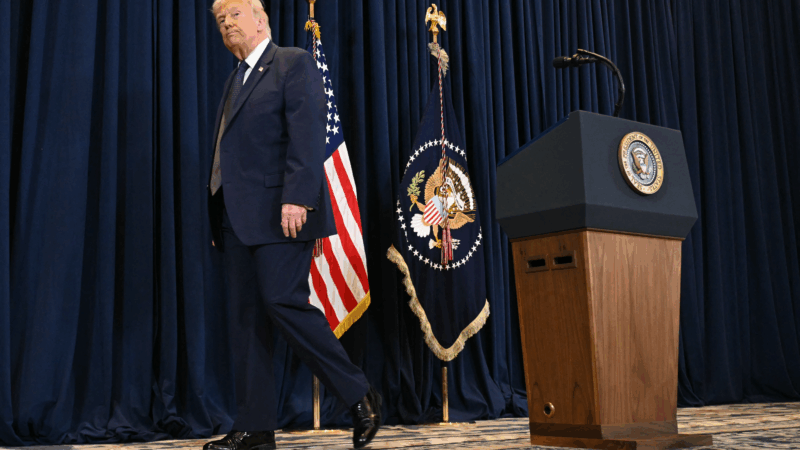

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.