With Trump’s crackdown on DEI, some women fear a path to good-paying jobs will close

In 1980, Lauren Sugerman was enrolled in a vocational program aimed at getting more women and Black Americans into the steel mills.

Then, an industrial giant came calling.

It had won a federal contract to maintain and repair elevators for the Chicago Housing Authority. Under an executive order signed 15 years earlier by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the company was obligated to at least try to recruit women and people of color.

Still, the hiring supervisor tried to talk Sugerman out of the job.

“I always called it a dis-interview,” she says. “It was basically, ‘You don’t want this job. This job is too dirty for you. This job is too dangerous for a girl. You really won’t like it.'”

She took the job anyway.

Sugerman credits that interview, and her subsequent career advocating for women in the trades, to that 1965 executive order. Known as EO 11246, it required federal contractors to identify and address barriers to employment, especially for women and people of color.

Now, six decades after its establishment, Sugerman is mourning its end.

“A huge loss to have what’s happening now”

President Trump revoked EO 11246 on his second day in office as part of his own executive order cracking down on what he sees as widespread and illegal use of “dangerous, demeaning, and immoral race- and sex-based preferences” under the guise of diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility.

“Illegal DEI and DEIA policies not only violate the text and spirit of our longstanding Federal civil-rights laws, they also undermine our national unity, as they deny, discredit, and undermine the traditional American values of hard work, excellence, and individual achievement in favor of an unlawful, corrosive, and pernicious identity-based spoils system,” Trump’s Executive Order 14173 states.

Trump also directed the government office that enforces the 1965 executive order to “immediately cease.”

The Labor Department is now expected to largely dismantle that office, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), since its primary task is gone.

Sugerman, who later tended to elevators and escalators at Sears Tower, then the tallest building in the world, wonders if the small forays that women have made in the construction trades since the 1980s will simply vanish.

“It is a huge loss to have what’s happening now,” she says.

The Labor Department did not respond to NPR’s request for comment on the impact the dismantling of EO 11246 may have on women and people of color.

Federal contractors employ 20% of the U.S. workforce

Trump’s plan to dramatically shrink the federal government targets myriad efforts focused on civil rights.

The end of EO 11246 cuts especially deep, given companies that do business with the government employ one out of every five workers in the U.S, says Jenny Yang, who headed OFCCP during the Biden administration.

By 1965, it was already illegal for employers to discriminate against workers and job applicants because of certain characteristics, including their gender and race. But the Johnson executive order obligated federal contractors across industries as varied as defense, academia and construction to take proactive steps to ensure compliance with the law, not just on government projects but at every office and job site.

“Not all companies are willing to look under the hood voluntarily to see whether they have a problem,” says Yang.

For federal contractors, looking under the hood meant analyzing their hiring and pay practices annually to try to figure out, for example, if women had better performance evaluations but were being paid less than men. They had to create plans for how to recruit and retain a diverse workforce that reflects the pool of available workers around them.

Matt Camardella, an attorney with Jackson Lewis who helps companies comply with employment law, says his clients took those responsibilities seriously.

“There was real risk in not doing this properly, or at all for that matter,” he says.

Investigations led to back pay

Every year, OFCCP audits hundreds of companies to see whether they are complying with EO 11246. Some of those audits lead to investigations, and some of those investigations lead to conciliation agreements.

For example, in 2020, Princeton University agreed to pay over $1 million in back wages and salary adjustments to more than 100 female professors after the government found pay disparities.

The university denied it had discriminated against women, finding fault with the government’s methodology, but agreed to look more closely at its pay practices.

Yang says over the past decade, OFCCP recovered more than $100 million for women in pay equity cases.

Now, though, things have gotten complicated.

Confusion over “illegal DEI”

Not only has Trump revoked Johnson’s executive order and halted its enforcement, but as part of his own executive order, Trump demanded that federal contractors certify that they’re not engaging in “illegal DEI.” He says ending these practices will allow people to compete based on merit.

Camardella says that’s left his clients confused.

“Nobody really understands what ‘illegal DEI’ means,” he says.

Camardella notes that nothing about federal anti-discrimination law has changed since Trump took office. He believes there’s nothing wrong with a company continuing to examine its pay practices, hiring and outreach to ensure it’s complying with the law.

“However, there may be a perception that somehow, that smacks of ‘illegal DEI,’ ” he says.

Paving a path to good-paying jobs

After six years maintaining and repairing elevators around Chicago, Sugerman had had enough. The work was hard, and the conditions even harder. She was often the only woman on a job site. She recalls men grabbing her breasts and making rape jokes and other vulgar comments in packed elevators.

She left her job and went to work for Chicago Women in Trades, a group that had sprung up in the early 1980s to help companies comply with EO 11246. In the decades since, the group has worked to create a pipeline of recruits, training women to become plumbers, carpenters, electricians, pipefitters, sheet metal workers and laborers.

In recent years, Chicago Women in Trades has been preparing for what’s promised to be a construction boom, with Congress’ passage of measures such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, which unleashed billions of new dollars for federal infrastructure projects.

“We’ve doubled our programs. We’ve doubled our staff. We’ve really tried to meet this moment,” says Executive Director Jayne Vellinga, who believes there’s no shortage of women who want to work in the trades and who can do the work well, so long as they can get a foot in the door.

At the heart of Chicago Women in Trades’ decades-long push is ensuring women have paths to good-paying middle-class jobs.

In Chicago, union carpenters, who are predominantly men, earn $55 an hour. In contrast, Vellinga says, nursing assistants, who are predominantly women, earn $18 an hour for a job that can be just as physically taxing.

Going from “something” to, perhaps, nothing

Even with EO 11246, progress has been slow.

Women still make up less than 5% of workers in the construction trades, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. That’s despite OFCCP’s goal dating back to the 1980s of having women perform 6.9% of the work on construction sites.

“None of these things were fantastic. I want to be clear about that. There was more of an emphasis on checking boxes,” Vellinga says. “But it was something.”

Now, she fears, some federal contractors won’t bother to consider women at all.

“They are not civil rights organizations. They’re builders,” she says. “For how many people will this fall off the priority list?”

Wendy Pollack helped found Chicago Women in Trades and now is a lawyer with the Shriver Center on Poverty Law. She warns that the end to EO 11246 will lead to a dire situation for women and people of color.

Pollack began her career as a carpenter. Like Sugerman, she encountered resistance on the job. Through it all, she had a mantra.

“You know, I might not change your hearts and minds, but at least I have the law on my side,” she would tell herself.

Now with diminished enforcement of civil rights laws under Trump, she wonders if that will still be true.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

The Trump administration’s plan to shrink the federal government is targeting multiple civil rights efforts. At the Labor Department, a draft proposal would nearly dismantle an office that investigates discrimination by federal contractors. NPR’s Andrea Hsu looks at what this could mean for workers. And here is where I want to let you know that this report includes descriptions of sexual assault.

ANDREA HSU, BYLINE: Unless you’re a company that does work for the federal government, you’ve likely never heard of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. Its primary role has been enforcing an executive order signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 at the height of the civil rights era. It required most federal contractors to take steps to ensure women and people of color have the same opportunities as others – that there aren’t barriers to employment or to promotions.

JENNY YANG: Not all companies are willing to look under the hood voluntarily to see whether they have a problem.

HSU: Jenny Yang oversaw this work at the Labor Department during the Biden administration. She notes federal contractors employ a whopping 20% of the U.S. workforce. So the old executive order has been a big deal. It’s given rise to groups like Chicago Women in Trades whose mission is getting women in the door. For decades, they’ve trained women to become plumbers, electricians, pipe fitters, sheet metal workers. In recent years, the group has worked hard to meet what’s expected to be a construction boom, with billions of new dollars approved for federal infrastructure projects. Jayne Vellinga is the group’s executive director.

JAYNE VELLINGA: We have doubled our programs. We’ve doubled our staff. We’ve really tried to meet this moment.

HSU: At the heart of this, she says, is ensuring women have a path to good-paying, middle-class jobs. In Chicago, a union carpenter earns $55 an hour. But now this progress is threatened. Trump revoked Johnson’s executive order on his second day in office. Lauren Sugarman, now Vellinga’s colleague at Chicago Women in Trades, is mourning its end.

LAUREN SUGARMAN: It is a huge loss – what’s happening now.

HSU: In 1980, Sugarman was enrolled in a vocational program aimed at getting more women and African Americans into the steel mills. Then an industrial giant came calling – a well-known company that had won a federal contract to maintain and repair elevators for the Chicago Housing Authority. Under Johnson’s executive order, the company had to at least try to recruit women. Sugarman recalls her interview.

SUGARMAN: I always called it a dis-interview. It was basically, you don’t want this job. This job is too dirty for you. This job is too dangerous for a girl. You really won’t like it.

HSU: She took the job anyway. It was hard work, and she did encounter problems. Sugarman says men grabbed her breasts and made rape jokes in packed elevators. But she stuck with the company for six years, eventually working on other projects, including at Sears Tower.

SUGARMAN: There were a hundred elevators and escalators in the building. And at that point, it was the tallest building in the world.

HSU: Now she wonders if the small forays that women have made in the trades will simply vanish. The Labor Department did not respond to NPR’s request for comment. Now, Jayne Vellinga will tell you – the 1965 executive order and the government’s work to enforce it only went so far.

VELLINGA: None of these things were fantastic. I want to be clear about that. There was more of an emphasis on checking boxes, but it was something.

HSU: Now she fears some federal contractors won’t bother to consider women at all.

VELLINGA: They are not civil rights organizations. They’re builders. For how many people will this fall off the priority list?

HSU: Plenty of women have proven they can do the work and do it well, she says, but you can prove nothing if you can’t get your foot in the door.

Andrea Hsu, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Italian fashion designer Valentino dies at 93

Garavani built one of the most recognizable luxury brands in the world. His clients included royalty, Hollywood stars, and first ladies.

Sheinbaum reassures Mexico after US military movements spark concern

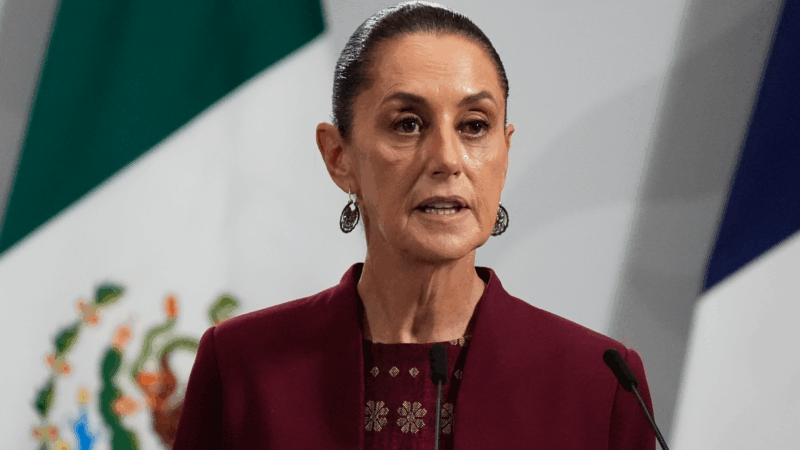

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum quelled concerns on Monday about two recent movements of the U.S. military in the vicinity of Mexico that have the country on edge since the attack on Venezuela.

Trump says he’s pursuing Greenland after perceived Nobel Peace Prize snub

"Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize… I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace," Trump wrote in a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.

Trump has rolled out many of the Project 2025 policies he once claimed ignorance about

Some of the 2025 policies that have been implemented include cracking down on immigration and dismantling the Department of Education.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.