When will the government reopen? Here’s how long past shutdowns lasted

The federal government has shut down for the first time since 2018.

The first shutdown in over five years began just after midnight on Wednesday, after a standoff between Senate Republicans and Democrats over healthcare spending culminated in their failure to pass a pair of last-ditch funding bills.

Both parties are blaming each other, though a new NPR/PBS News/Marist poll shows that more Americans hold Republicans responsible for the impasse.

The shutdown means several hundred thousand federal employees and active-duty service members will work without pay. It throws into question the operating status of sites like national parks and the Smithsonian Institution. And, while services like Social Security benefits and passport applications will continue, they could start to see delays.

Some of those impacts could be felt sooner than others. And it’s not clear how long the shutdown could stretch on.

As history shows, multiweek shutdowns are relatively rare, but have become more common in recent decades.

Loading…

The government’s most recent shutdown — from December 2018 to January 2019 — was the longest in history, timing out at 35 days.

It began on Dec. 22, 2018, fueled by Democrats’ refusal to meet President Trump’s demand for funding to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.

It ended on Jan. 25, 2019, after a series of escalating disruptions — including widespread travel delays caused by overworked air traffic controllers calling out sick — and mounting pressure on Trump, including from his own party. He ultimately agreed to a temporary spending deal that reopened the government without funding for the wall.

The five-week impasse cost the U.S. an estimated $3 billion in lost GDP, according to the Congressional Budget Office. It was a partial shutdown, as Congress had passed some bills to fund several agencies before the deadline. This time around, Congress has passed none.

How common — and lengthy — are government shutdowns?

There have been 20 “funding gaps” since Congress introduced the modern budget process in 1976, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB).

But many of those were only a few days long: Since 1981, there have been 10 funding gaps of three days or fewer — mostly over a weekend when the impact to government operations was relatively minimal.

Only a handful of shutdowns have lasted more than two weeks — and they were all within the last 30 years.

The government shut down twice in 1995: for five days in November and another 21-day window between December and January 1996.

Both of those shutdowns were due to disagreements between President Bill Clinton and the Republican-controlled House — led by Speaker Newt Gingrich — about how to balance the budget. Republicans, who had just gained a House majority for the first time in 40 years, wanted to cut social programs and repeal Clinton’s 1993 tax increase.

The government reopened after Republicans, whom polls showed a majority of Americans blamed, accepted Clinton’s compromise proposal. It got the title of the longest shutdown in history and is widely seen as the start of a new era of political gridlock.

After that, the government didn’t shut down again for nearly 20 years. But it reached another impasse in 2013, when the Republican-controlled House refused to pass a spending bill that funded the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.

Then-freshman Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas led hard-liners in their opposition to Obamacare, including giving a now-infamous 21-hour protest speech on the Senate floor. Obama and Democratic lawmakers repeatedly rejected Republicans’ proposals, leading to a shutdown.

The government reopened after 16 days, thanks to bipartisan negotiations in the Senate that resulted in only minor changes to Obamacare. Then-House Speaker John Boehner, a Republican, concluded: “We fought the good fight, we just didn’t win.”

A 2023 report from the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee Democrats found that the shutdown reduced GDP growth by $20 billion and cost the U.S. at least $2 billion in lost work hours.

Government shutdowns are a relatively recent phenomenon

The appropriations process is notoriously complicated, with each of 12 House and Senate subcommittees required to produce a bill to fund particular areas of the government. Those measures must pass both chambers of Congress and get the president’s signature before the fiscal year begins on Oct. 1.

Throughout history, it hasn’t been unusual for parts of the federal government to experience lapses in funding when the appropriations process doesn’t move quickly enough. But for nearly two centuries, those gaps in funding didn’t actually stop the government from operating.

“It was thought that Congress would soon get around to passing the spending bill and there was no point in raising a ruckus while waiting,” Charles Tiefer, a former legal adviser to the House of Representatives, told NPR in 2013.

That changed in 1980 and 1981, when U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti singlehandedly established the basis for government shutdowns.

As intensifying political divisions led to recurring funding gaps in the late 1970s, an obscure law called the Antideficiency Act came under increased legal scrutiny. President Jimmy Carter sought Civiletti’s advice: Can a federal agency legally allow its employees to keep working in the absence of appropriations?

No, Civiletti wrote in an April 1980 legal opinion.

“It is my opinion that, during periods of ‘lapsed appropriations,’ no funds may be expended except as necessary to bring about the orderly termination of an agency’s functions,” he continued.

The following year, in a second opinion, Civiletti clarified that some government functions could continue during a funding lapse if they were necessary for the “safety of human life or the protection of property.”

Civiletti’s stance seemingly opened the floodgates. There were eight government shutdowns — none lasting longer than three days — in the 1980s, another three in the 1990s and three more in the 2000s, according to House data.

Civiletti, who died in 2022, said he was surprised to see how many government shutdowns his single opinion — “on a fairly narrow subject” — had ushered in over the decades.

“I couldn’t have ever imagined these shutdowns would last this long of a time and would be used as a political gambit,” he told the Washington Post in January 2019, amidst the history-making shutdown.

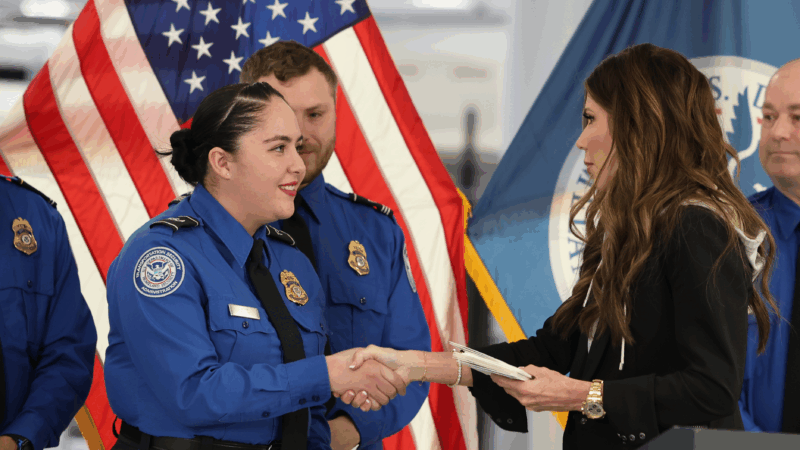

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

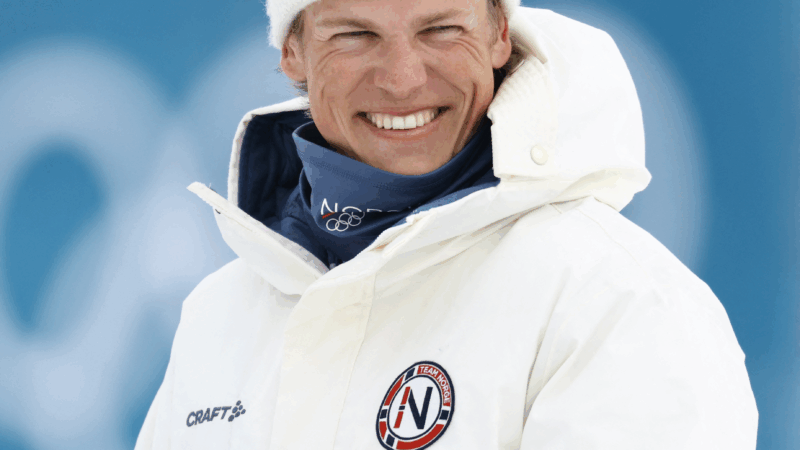

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.