What we know about the devastating storm in Western Alaska

In the late night hours of Oct. 11, the remnant of Typhoon Halong slammed Alaska’s southwest coast, bringing hurricane-force winds and record flooding to numerous Alaska Native villages on the coast.

Evacuees and rescuers describe massive destruction: utility poles snapped in half, boardwalks – the roads and sidewalks in many tundra villages – uprooted, houses floated off their foundations, some with families still inside.

According to the state, more than a thousand people are displaced – some have no home to return to. One woman was found dead, and two of her family members remain missing. The state of Alaska’s Emergency Operations Center is in its highest-possible level of emergency response. Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy has called for a federal disaster declaration for the region.

Where is most affected?

The remnant of Typhoon Halong had sweeping impacts across the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta – an area in Western Alaska hundreds of miles from the U.S. road system and about the size of Oregon, with dozens of small villages scattered throughout.

The coastal villages of Kipnuk and Kwigillingok took the brunt of the storm, and are being almost entirely evacuated, per the State Emergency Operations Center.

In addition, regional health officials have listed more than a dozen villages where substantial damage has been reported, and the state says that nearly 50 have reported some impacts. Damages are still being assessed and it’s not clear yet how many people will be permanently displaced.

Evacuations slowed and complicated by remoteness

Initially, many of the displaced sheltered in schools throughout the region. But with heating, fuel, water, and sewer systems strained – local officials said it wasn’t safe for people to stay.

Emergency responders started to evacuate people to Bethel, the 6,500-person hub community of the region, which saw comparatively little damage from the storm. But the emergency shelter there reached capacity quickly. Within two days, displaced residents were being flown to Anchorage, 400 air miles away.

The evacuation process was significantly slowed by the remoteness of the area. With runways damaged in at least one village, some evacuations had to rely on helicopters. U.S. Coast Guard rescue crews recounted moving people out of communities six at a time.

Buggy Carl, tribal administrator in Kipnuk, said despite the damage, it’s daunting for community members to leave the place they have such deep history. The villages of the Kuskokwim Delta are the traditional homelands of generations of Yup’ik people.

“I know their mindset, that their heart is here,” he said on Oct. 15. “They don’t know anywhere else to go, because, you know, they grew up here. They have their own food throughout the year long, doing subsistence hunting. They just can’t leave.”

That connection to land and food is a primary concern for many facing longer-term relocation. Some who’ve stayed behind in destroyed villages have done so with the goal of salvaging what subsistence foods they could – moose, musk ox, beluga, salmonberries, salmon, seal oil, emperor goose.

Others speak of the heart-wrenching loss of ancestors’ graves. In Kwigillingok, residents reported seeing unearthed coffins piled up at the end of the airport runway after the floodwaters receded.

How was this typhoon remnant so destructive?

Initially, climate models showed the remnant typhoon tracking north. But according to Rick Thoman, an Alaska Climate Specialist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the storm picked up speed and shifted suddenly, taking its path right toward the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta coast. That was only a day and a half before the storm reached Alaska waters – a tight timeline for evacuation.

This region is also on the forefront of climate change. Permafrost – or ground that is frozen year-round – underpins many of these villages and is thawing, leading to rapid erosion and instability. The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium says nearly 150 communities in Alaska – many in the Y-K Delta – will need to relocate fully or partially in the coming years because of permafrost thaw, land subsidence, erosion, or some other combination of climate-driven factors.

The hundreds of square miles of tundra of the Delta are very close to sea level, and many communities don’t have much high ground. And while some homes and buildings are built on pilings driven deep into the ground, many others sit on posts or other less stable foundations.

These factors combine to make the land more vulnerable to storm-driven erosion, and structures more vulnerable to flood damage.

What’s next?

If communities choose to rebuild, it will be difficult.

It’s expensive, and logistically complex, to get building materials out to these remote villages.

The region is also still recovering from major flooding in August of last year – Kipnuk, one of the villages hardest hit by the remnants of Typhoon Halong, received one of the first-ever federal disaster declarations for an Alaska tribe in the wake of that flooding.

You can follow more of KYUK’s coverage on the storm here.

Nathaniel Herz and Evan Erickson contributed to this reporting

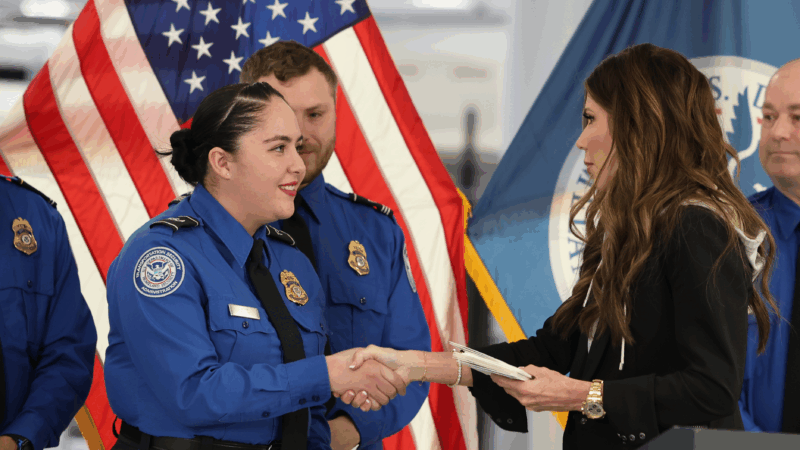

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

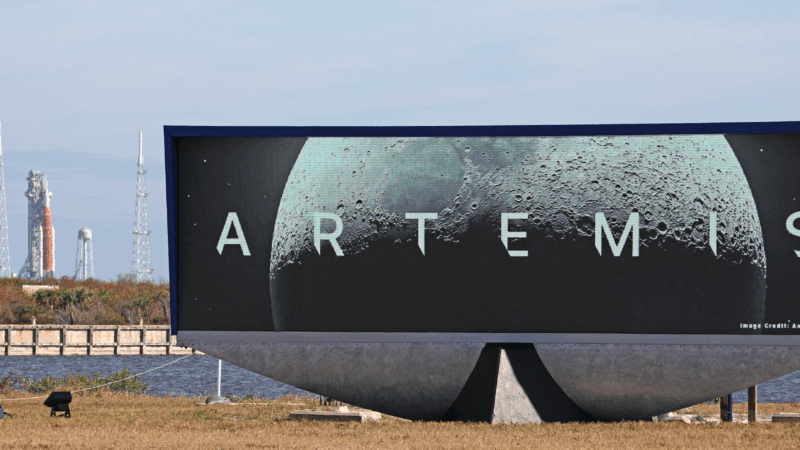

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

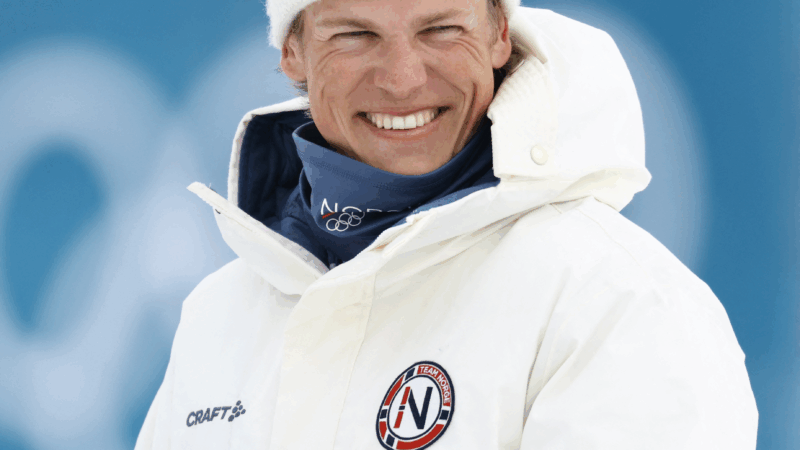

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.