What is a universal injunction and how did the Supreme Court limit its use?

The Supreme Court’s decision to limit universal injunctions, which gives lone judges the power to limit executive orders, is seen as a victory for the Trump administration, which will now enjoy a freer hand to implement policy.

Friday’s decision centered on President Trump’s executive order stating that children of people who enter the U.S. illegally or on a temporary visa are not entitled to automatic citizenship. Immigrant rights groups and 22 states sued the government over the order. Three federal district court judges struck it down and issued a universal injunction preventing its enforcement.

But instead of ruling on whether president’s action on birthright citizenship violated the 14th Amendment or the Nationality Act, the Supreme Court’s ruling focused on whether federal courts have the power to issue such nationwide blocks.

“Universal injunctions likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has given to federal courts,” the conservative majority said.

Speaking at the White House briefing room after the decision was issued, President Trump called it a “monumental victory for the Constitution, the separation of powers and the rule of law.”

Here’s a look at universal injunctions and how they’ve been used.

What is a universal injunction?

In short, a universal injunction is a court order that prohibits the government from enforcing a law, regulation or policy against anyone – not just the plaintiffs in a case. It applies nationwide (and is sometimes called a “nationwide injunction”) regardless of the issuing court’s jurisdiction.

“An injunction is an order by a court telling somebody to do something or not do something,” explains Samuel Bray, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame. Usually injunctions protect the parties to the case. But a universal injunction “controls how the federal government acts toward anyone.”

He says universal injunctions are “a recent innovation” and their use has seen “a meteoric rise over the last 10 years” in tandem with an increase in executive orders issued by the administrations of presidents Barack Obama, Trump and Joe Biden.

In the past, justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito have all criticized universal injunctions, with Thomas referring to them as “legally and historically dubious,” and noting that they were rare before the 1960s.

In 1937, Congress passed a law requiring three-judge panels for cases that challenged federal laws, with those decisions appealable directly to the Supreme Court.

It was designed to limit the power of individual judges to halt New Deal programs and had the effect of streamlining the appeals process. It “substantially delayed disputes over universal injunctions,” says Michael Morley, a professor at Florida State University College of Law. This “expedited path somewhat reduced the likelihood that disputes over universal injunctions would arise,” he says. But in 1976, the law was scaled back.

What does the Supreme Court order mean?

First, the ruling means that using injunctions as a default option to block Trump executive orders is effectively dead. Groups have used nationwide injunctions to block Trump’s declaration that the federal government will only recognize two genders, and the Department of Homeland Security’s departure from a decades-old policy that encouraged Immigration and Customs Enforcement to avoid places of worship.

The decision today means federal courts can’t grant universal injunctions based on fairness, justice, and principles of equity, rather than the letter of the law, says Bray. “It will remove universal injunctions as the default remedy in a challenge to executive action,” he adds.

Moving forward, however, the decision will also likely mean that plaintiffs will change the manner in which they bring cases to federal courts.

Next up, class action lawsuits

“The central front in litigation against the federal government is going to shift from universal injunctions to class actions,” Bray says, because such actions could afford protection to more than just an individual plaintiff.

Morley believes that as a result, the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23, also known simply as Rule 23, which refers to a legal process for certifying a class action lawsuit in federal court, will be “the next major battleground.”

In addition to class actions, he says we’re likely to see increased use of state plaintiff suits – where a state sues to protect its own interests or its residents – along with organizational standing, which allows groups to sue on their own behalf if directly harmed, and associational standing, which lets organizations sue on behalf of their members if certain conditions are met.

“Despite the ruling today, there are other procedural mechanisms the plaintiffs have already begun to use… to get effectively universal relief,” he says. “[T]hese are the next frontiers that the Court’s ruling today is going to push these disputes to.”

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.

Reporter’s notebook: A Dutch speedskater and a U.S. influencer walk into a bar …

NPR's Rachel Treisman took a pause from watching figure skaters break records to see speed skaters break records. Plus, the surreal experience of watching backflip artist Ilia Malinin.

In Beirut, Lebanon’s cats of war find peace on university campus

The American University of Beirut has long been a haven for cats abandoned in times if war or crisis, but in recent years the feline population has grown dramatically.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

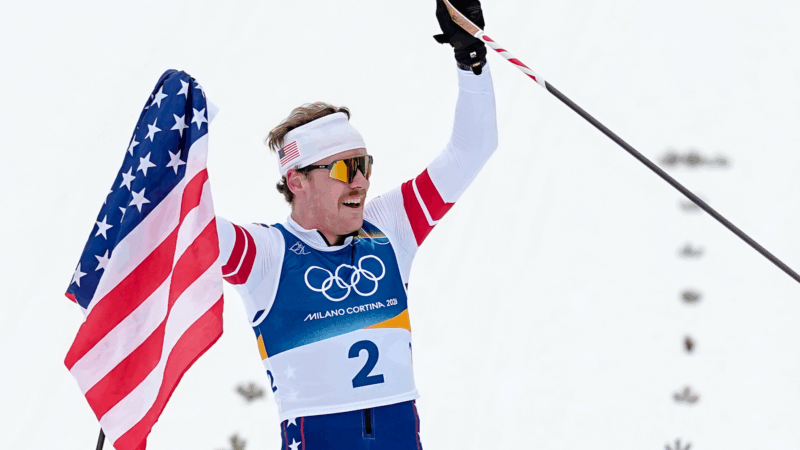

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.