Ukraine’s DIY drone makers are helping fighters on the front lines

KYIV, Ukraine — In the courtyard of a group of ordinary-looking Kyiv apartment blocks, a stairway leads down to a small basement apartment.

Three big dogs run out into the hallway when newcomers arrive. Inside a main room, three people sit hunched over desks. Around them, tables are laden with parts and small hand tools like pliers and tweezers. Boxes of tiny plastic propellers sit on the floor and wall shelves are stacked with carbon-fiber frames.

This is the workshop for a secret drone-making operation. It turns out about 100 attack drones for Ukraine’s military every month.

Andrii Yukhno, who supervises this operation, reaches up to close one of the windows. They are covered with paper to block prying eyes. With the windows cracked open, children’s voices from a nearby kindergarten fill the room. “But don’t worry,” he says, “we don’t show our drones to the children.”

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Yukhno earned his living as a barista in a coffee shop. But he says the war turned him into a full-time volunteer in one of the many DIY weapons factories arming the fighters on Ukraine’s front lines.

Earlier, he supported the war effort differently.

“In the beginning I was delivering food and medicine to people in Kyiv, anything to help,” he says. “But then I moved on to bigger and bigger things.”

He took online drone-making classes — there are several offered in Ukraine — and started making first-person view (FPV) drones in this basement apartment.

These are manually piloted unmanned aerial vehicles. At the front lines, they are equipped with a high-explosive payload the drone makers refer to as “candy.”

Operators, wearing goggles with portable screens strapped around their heads to show a livestream view from the drone’s camera, fly the drones into combat. They steer the drones directly into enemy targets — vehicles, trenches, personnel, even tanks — to destroy them with explosives.

Yukhno is now training others. One of his trainees is 35-year old Khrystyna Pashchenko, who arrived here a couple of weeks ago.

“Andrii praised my work, so I’m already soldering the engines to the motherboard,” she says.

Pashenko says she’s good at attention to detail. She used to enjoy cross-stitch as a hobby.

Today, instead of working with needle and thread, she holds a soldering wand puffing out thin wisps of smoke. She recently left her job as a manager in a company that helped businesses appear higher in internet searches. She earns nothing now as a volunteer, but says that when the war started, her old work no longer felt meaningful.

“But now I feel super excited and a little bit proud of myself that I can do something useful,” she says. “That I can help in the war effort. And the guys who are using our drones on the front lines send us videos saying how thankful they are, and that’s hugely motivating.”

Factories and mom-and-pop operations churn out drones

The war in Ukraine is now largely being fought with drones, with more than half the destruction on the front line caused by FPV drones, according to the Ukrainian general staff. Ukraine is at the cutting edge of drone innovation but lags behind Russia in drone production, experts say.

Necessity has transformed this country into a nation of drone-makers, who churn them out from factory assembly lines and mom-and-pop operations like the one in the basement apartment in Kyiv.

Yukhno says he knows of at least 15 like his in Kyiv alone.

For Sasha Ptashnyk, who was a dancer before the full-scale invasion, making drones is a way to help end this war on the best terms Ukraine can get.

“Of course I would love for us to be victorious and get all our land back,” he says. “But we have to be more realistic. We are fighting a huge foe. We must be sober.”

What’s most sobering, he says, is that Ukraine’s greatest ally, the United States, may be abandoning his country. Ukrainians have felt stunned by the Trump administration’s turnabout on Ukraine. They watched as their own president was berated and accused of being ungrateful in late February in the Oval Office, and see President Trump as cozying up to Russian President Vladimir Putin as he pushes to end the war.

Ukraine and Russia are competing with each other in drone technology

A 30-minute drive away from the improvised weapons workshop, the sharp whine of a drone’s four motors cuts through the country air. Oleksii Babenko is testing one of his company’s new drones in a field surrounded by forest on the outskirts of Kyiv.

Babenko is the CEO of one of Ukraine’s most successful drone-making companies, Vyriy. It recently reached a milestone: it is now turning out drones made entirely of Ukrainian-sourced parts — from the carbon-fiber frames to the intricately mounted motors and cameras.

Babenko says that’s important at a time when Ukraine has to increasingly rely on itself.

“From the start of this war, every time Ukraine needs something, we have to ask other nations for it over and over again,” he says. “So the only way to stay strong is to make everything here. Ukrainian soldiers, Ukrainian manufacturers…”

The whereabouts of Vyriy’s factory are a closely guarded secret, because Russia tries to target Ukraine’s drone-making operations. But Babenko lets NPR watch a drone test on a recent sunny afternoon.

Sunlight glints off what looks like fishing wire strewn through the trees and bushes. It is, in fact, fiber optic cable — hundreds of yards of it — spooled out by the drone, transmitting control signals and video feeds between the operator and the flying machine. The system is impossible to jam with blasts of radio waves, a common counter-measure in the field.

Babenco says Ukraine made this breakthrough in 2023. But Russia quickly caught up.

Oleksandr Kamyshin, an advisor to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on strategic affairs, estimates that Russia is, most of the time, several months behind Ukraine in drone innovation. But he says the Russians have much bigger production capabilities. So he calls this war a technological race.

“Once you’ve got a technology, the other side tries to counter this technology,” he tells NPR. “And then you have to find another solution and the other side tries to counter that. Within the war is a constant war of innovations and technologies.”

He says Ukraine is capable of producing up to 5 million FPV drones per year and has more than 150 manufacturers that can produce up to 100,000 drones per month.

Volunteers have left their fields of expertise for now to make drones

Back in the basement apartment in Kyiv, a drone whirs furiously in the center of the room as it is tested in a metal cylindrical frame that allows it to fly, twist and flip.

Part-time drone maker Oleh Halaidych has just shown up and sits down at his workstation. This biophysicist, who has a Ph.D. in the study of stem cells, says making drones is probably the quickest, most impactful way of helping Ukraine.

“I think we are all motivated because we see that this is a cheap and accessible way to make weapons,” he says. “They kill the enemy and destroy his armored vehicles.”

Halaidych says the war has made many people who work in culture or the arts and sciences realize that it’s a time to pursue different options.

“Science is slow,” he says. “And we need to do something to protect ourselves right now.”

High-speed trains collide after one derails in southern Spain, killing at least 21

The crash happened in Spain's Andalusia province. Officials fear the death toll may rise.

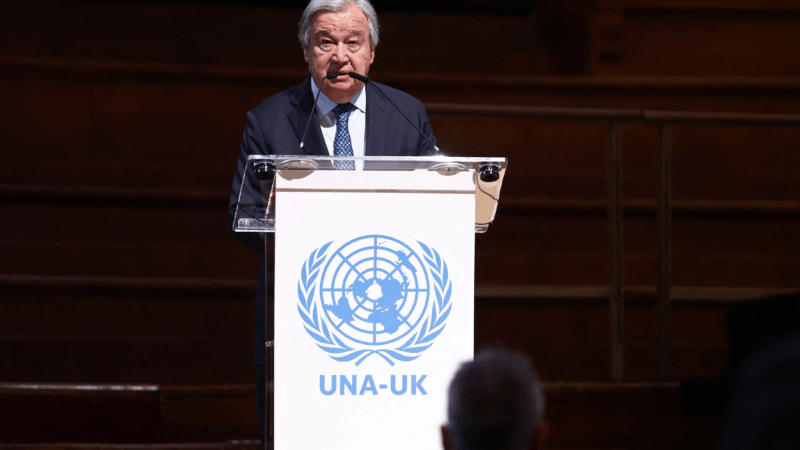

United Nations leaders bemoan global turmoil as the General Assembly turns 80

On Saturday, the UNGA celebrated its 80th birthday in London. Speakers including U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres addressed global uncertainty during the second term of President Trump.

Parts of Florida receive rare snowfall as freezing temperatures linger

Snow has fallen in Florida for the second year in a row.

European leaders warn Trump’s Greenland tariffs threaten ‘dangerous downward spiral’

In a joint statement, leaders of eight countries said they stand in "full solidarity" with Denmark and Greenland. Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen added: "Europe will not be blackmailed."

Syrian government announces a ceasefire with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces

Syria's new leaders, since toppling Bashar Assad in December 2024, have struggled to assert their full authority over the war-torn country.

U.S. military troops on standby for possible deployment to Minnesota

The move comes after President Trump again threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to control ongoing protests over the immigration enforcement surge in Minneapolis.