Trump’s homelessness executive order is ‘cruel,’ says Alexandria, Va. mayor

Alexandria, Virginia Mayor Alyia Gaskins says President Trump’s executive order to remove homeless people off the streets is “cruel” and takes a “callous command and control approach.”

“It requires states and cities like mine to demonstrate aggressive enforcement,” Gaskins told Morning Edition. “It ends support for housing first policies. It encourages the expanded use of law enforcement all at a time when we know that the criminalization of homelessness doesn’t work.”

Trump signed an executive order last week aimed at managing homelessness in the U.S. by committing people living on the streets to mental health institutions or drug treatment centers without their consent, which he says will “restore public order.”

Housing first — a homeless assistance approach aimed at getting people into permanent housing and then offering them mental health or addiction treatment — has had bipartisan support for about two decades. Supporters argue that a lack of affordable housing is why homelessness rates continue to rise and that a housing first approach keeps people off the streets.

More than 770,000 people were living on the streets or shelters last year, up 18% from the previous year, leading conservatives to question the approach and to suggest more hardline practices.

Trump’s order also directs the Secretaries of Housing and Urban Development, Transportation, and Health and Human Services to assess federal grant programs and prioritize funding to cities that crack down on open drug use and encampments. Trump says his goal is to limit public safety threats from those who he says pose a risk to themselves and others.

Gaskins has managed an affordable housing investment program at the Center for Community Investment and was a senior program officer at Melville Charitable Trust, a national philanthropic organization devoted to ending homelessness. She says housing first has decreased homelessness in Alexandria, Va. by 11%. But she’s worried the funding Virginia receives from the federal Department of Housing and Community Development, which enforces housing first initiatives, could be stripped away.

She spoke with NPR’s A Martínez about what Trump’s executive order will mean for homelessness in cities like Alexandria.

The following excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

A Martínez: What was your impression of President Trump’s executive order on this?

Alexandria, Va. Mayor Alyia Gaskins: My first reaction was that this executive order is cruel and it uses a callous command and control approach. It requires states and cities like mine to demonstrate aggressive enforcement. It ends support for housing first policies. It encourages the expanded use of law enforcement all at a time when we know that the criminalization of homelessness doesn’t work. It doesn’t create housing, it doesn’t treat illness, it doesn’t make streets safer, and it doesn’t get at the root of the problem, which is the need for more housing. I wish we were focused on solutions instead.

Martínez: Would it take local control away from cities like yours?

Gaskins: It puts federal funding at risk. I will also tell you in Virginia, we receive funding from the Department of Housing and Community Development. As a grantee, we’re required to use a housing first approach. So not only does it make it confusing as to whether or not we’ll receive federal funding, it also has implications for our state funding that we use to address homelessness.

Martínez: You mentioned housing first. This executive order would make it easier for states and cities to move people into mental health or addiction treatment, including involuntary commitment for people who are considered a risk to themselves and others. So it’s a shift from policies that get people into housing first. So why shouldn’t people get treatment first instead of housing first?

Gaskins: What we know is that at the end of the day, we want our solutions to be successful and that in many cases when you force people into treatment — especially against their will — it creates situations that are not sustainable. Oftentimes they try to remove themselves from that treatment, or as soon as they finish those programs, they’re then right back out on the street. Whereas when we do a housing first model, we focus on getting people the stability they need so that treatment and other interventions actually work and that they do so in a way where we put people first and they have trust in the process and can build the relationship they need in order to sustain that care and support.

Martínez: In your city, how would people be affected by this executive order?

Gaskins: The sad thing in our city is that we’re actually seeing an 11% drop in homelessness. We’ve been successful in our interventions because we focus on housing first, because we have invested in more mental health services and supports, and because we have a focus on outreach that does not begin with public safety, but begins with housing, begins with human and community services and coordination across all our departments, as well as partnerships in the community. If this order goes into place, what it means is that those approaches we may not be able to do or we might lose the funding to be able to do what is actually working in our community and that people who are on the streets, who we have been working to build relationships with, who we are in the process of getting them the support they need, could potentially be arrested.

Editor’s note: The Melville Charitable Trust is a financial supporter of NPR.

This digital story was edited by Obed Manuel. The radio version was edited by Reena Advani and produced by Milton Guevara and Nia Dumas.

Transcript:

A MARTÍNEZ, HOST:

One of President Trump’s recent executive orders makes it easier to remove homeless people from the streets. His latest action builds on a Supreme Court ruling last year that said cities could punish people for sleeping outside, even if they have nowhere else to go. We’re going to talk about this with Mayor Alyia Gaskins of Alexandria, Virginia. She previously managed an affordable housing investment program at the Center for Community Investment and was a senior program officer at Melville Charitable Trust, which is a national philanthropic organization devoted to ending homelessness and also a financial supporter of NPR. Mayor, what was your impression of President Trump’s executive order on this?

ALYIA GASKINS: My first reaction was that this executive order is cruel, and it uses a callous command-and-control approach. It requires states and cities like mine to demonstrate aggressive enforcement. It ends support for Housing First policies. It encourages the expanded use of law enforcement, all at a time when we know that the criminalization of homelessness doesn’t work. It doesn’t create housing. It doesn’t treat illness. It doesn’t make streets safer, and it doesn’t get at the root of the problem, which is the need for more housing. I wish we were focused on solutions instead.

MARTÍNEZ: Right. Would it take local control away from cities like yours?

GASKINS: What it does is it makes the control of how we pursue homelessness and how we work to end homelessness in our community – it puts federal funding at risk. I will also tell you, in Virginia, we receive funding from the Department of Housing and Community Development. As a grantee, we’re required to use a Housing First approach. So not only does it make it confusing as to whether or not we’ll receive federal funding. It also has implications for our state funding that we use to address homelessness.

MARTÍNEZ: You mentioned Housing First. This executive order would make it easier for states and cities to move people into mental health or addiction treatment, including involuntary commitment for people who are considered a risk to themselves and others. So it’s a shift from policies that get people into housing first. So why shouldn’t people get treatment first instead of housing first?

GASKINS: What we know is that at the end of the day, we want our solutions to be successful and that in many cases, when you force people into treatment, especially against their will, it creates situations that are not sustainable. Oftentimes, they try and remove themselves from that treatment, or as soon as they finish those programs, they’re then right back out on the street. Whereas, when we do a Housing First model, we focus on getting people the stability they need so that treatment and other interventions actually work and that they do so in a way where we put people first and they have trust in the process and can build the relationship they need in order to sustain that care and support.

MARTÍNEZ: In your city, Mayor – in Alexandria, Virginia – how would people be affected by this executive order?

GASKINS: Yeah. So the sad thing in our city is that we’re actually seeing an 11% drop in homelessness. We’ve been successful in our interventions because we focus on housing first, because we have invested in more mental health services and supports and because we have a focus on outreach, that does not begin with public safety, but begins with housing, begins with human and community services and coordination across all our departments, as well as partnerships in the community. If this order goes into place, what it means is that those approaches, we may not be able to do, or we might lose the funding to be able to do what is actually working in our community and that people who are on the streets, who we have been working to build relationships with, who we are in the process of getting them the support they need, could potentially be arrested.

MARTÍNEZ: That is Mayor Alyia Gaskins of Alexandria, Virginia. Mayor, thank you very much.

GASKINS: Thank you.

In a historic vote, Tennessee Volkswagen workers get their first union contract

Two years ago, the successful union drive at this plant was expected to spark victories throughout the South. But now, as members vote to make their contract official, momentum has fizzled.

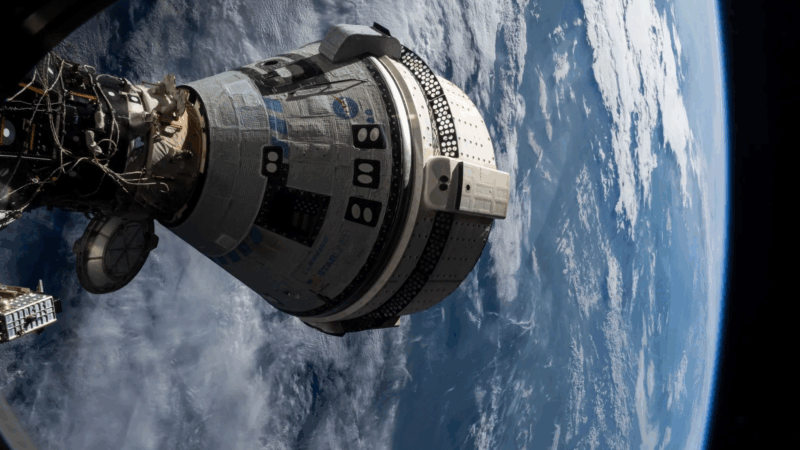

NASA chief blasts Boeing, space agency for failed Starliner astronaut mission

NASA's Jared Isaacman slammed Boeing for failures with its Starliner spacecraft, which was deemed unsafe to return its crew of two astronauts from the International Space Station

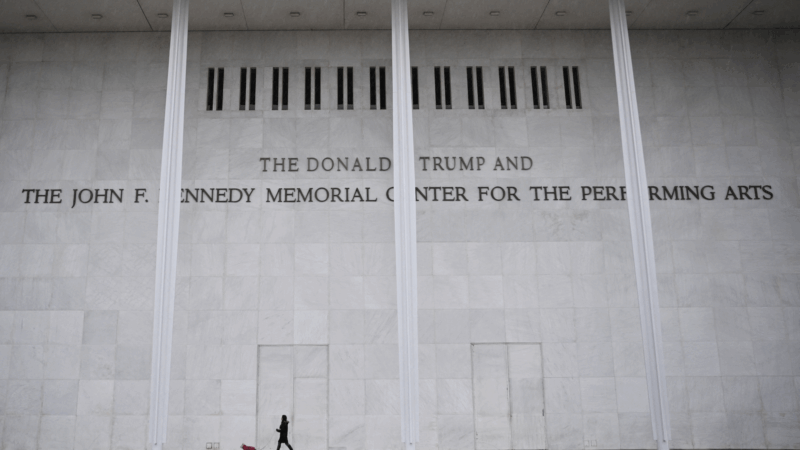

Internal memo details cosmetic changes and facility repairs to Kennedy Center

Trump announced his plans to close the Kennedy Center entirely for two years "for Construction, Revitalization, and Complete Rebuilding." The announcement came after many prominent artists canceled existing scheduled appearances.

R&B stars consider two ways to serve an audience

Two albums released the same day — Jill Scott's return from a long absence, and Brent Faiyaz's play for a mid-career pivot — offer opposing visions of artistic advancement in the genre.

Baby chicks link certain sounds with shapes, just like humans do

A surprising new study shows that baby chickens react the same way that humans do when tested for something called the "bouba-kiki effect," which has been linked to the emergence of language.

American Jordan Stolz speedskates to a third Olympic medal — silver this time

U.S. speedskater Jordan Stolz had a lot of hype accompanying him in these Winter Olympic Games. He's now got two gold medals, one silver, with one event to go.