Trump threatened school funding in Maine. Here’s how that money is used

Jonathan Moody runs a rural school district in and around Skowhegan, Maine, about 90 miles north of Portland. His office is in an old, converted farmhouse; the conference room was once a chicken coop.

“I drive 30 minutes to work and I have no stoplight,” Moody says with a chuckle.

Moody grew up going to rural schools nearby, and now he’s dedicated his career to leading them. But the rurality of his district, MSAD 54, coupled with high poverty, has made school funding “a tremendous challenge,” Moody says.

Because of that, his schools rely heavily on federal dollars: Seventy-four of the district’s staff positions are funded by federal grants, and federal money helps pay for free school meals, special education, mental health services and a robust after-school program, among other things

Moody says federal funds help educate “our most needy students. They’re the backbone of our [academic] intervention system. They help students get on pace.”

But as Maine schools find themselves in the middle of a political battle with the Trump administration, that federal support is at risk. President Trump threatened to cut federal funding for K-12 education in Maine, which amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars a year, after Gov. Janet Mills refused to follow an executive order banning transgender athletes from school sports.

In a now famous exchange, Trump told Mills, “you’re not going to get any federal funding at all” if her state refused to follow the administration’s interpretation of sex-discrimination laws. Mills’ response: “See you in court.”

There is now ongoing litigation that could take months to resolve.

“This is the Trump administration basically holding funding for our most vulnerable students, largely low-income students, hostage for states and school districts to implement their policies of preference,” says Rebecca Sibilia of Ed Fund, a school finance research nonprofit. “This is completely unprecedented in terms of the history of funding for schools.”

For educators in Maine, it’s also incredibly unsettling.

“Probably more so today than ever, the national narrative impacts staff,” Moody says, “and they’re nervous.”

What federal dollars do for public schools

U.S. schools get most of their funding from state and local sources, but between 6 and 13% of overall school funding comes from the federal government, according to a 2018 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. The money is supposed to help schools serve students who need more support to succeed, including those from low-income families, English language learners and students with disabilities.

Sibilia says while those federal dollars may seem like an expendable fraction of a school budget, “it actually becomes very tangible when you think about laying off 1 out of 10 teachers, when you think about reducing teacher salaries, when you think about reducing the number of classrooms in a school. That all becomes very real.”

Two of the largest federal funding streams for K-12 schools are Title I, which supports schools serving low-income students, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which helps provide specialized services for students with disabilities.

The federal government is legally required to provide Title I and IDEA funding, and, unless Congress steps in, any effort to cancel that money would lead to a lengthy judicial process, Sibilia says.

How Title I serves students in one rural Maine district

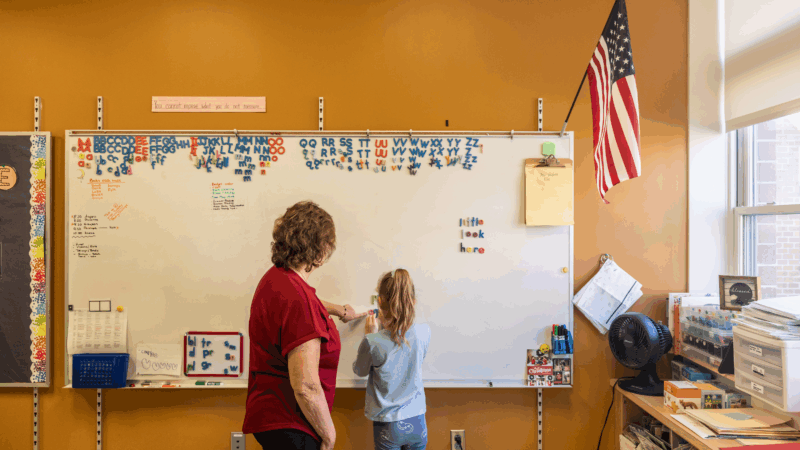

Title I is the largest federal grant at Mill Stream Elementary School, which sits above a tributary of the Kennebec River outside Skowhegan.

Rural schools like those in Jonathan Moody’s district are especially reliant on federal funds because they have a smaller local tax base to support school funding.

And part of the benefit of federal grants is they are relatively flexible and allow local leaders to use the money to best serve their unique student population.

Title I has helped Mill Stream – and all the elementary schools in the MSAD 54 district – pay for trained interventionists who provide targeted instruction for struggling students. It also pays for roving teaching assistants, and helps keep class sizes small, which benefits all students.

Barbara Welch, who has been an educator in this district for 37 years, says her salary is paid for entirely by Title I. Her primary job is to coach other teachers, and to track how well their interventions are working.

Welch says the district strategically focuses Title I services on the youngest students, especially those in kindergarten through second grade.

“The sooner that we can get to our students that are struggling, and help them get untangled, the chances of them needing services later are greatly decreased.”

And their efforts seem to be working: “Our data reveals that we’re doing the right thing because our students enter third grade not needing Title I interventions,” she says.

In addition to what happens during the school day, Welch says “parent outreach is a huge part of our Title I funding.”

The district uses Title I money to host events like “Learning Paloozas,” where families can engage in enrichment activities with their children, and take home books and other school supplies, to encourage learning beyond school.

“The school brings us all together, it provides opportunities for those in our communities to come together for a common reason and they build friendships and connections,” says Welch.

Without federal dollars, schools like Mill Stream would have to pull back on these kinds of enrichment and intervention efforts.

But Moody says there isn’t much left to cut. “[We are] already at a bare minimum, and so if you’re going to reduce, you reduce staffing, which is programming for kids.”

Beyond the classroom, federal dollars help feed students and support their mental health

Moody says his district has long benefited from federal programs that provide free meals at school.

About two-thirds of the school community struggles with poverty, and food insecurity is a major issue for his students. The state of Maine participates in several U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) programs that provide free meals at school. Students who attend MSAD 54’s after-school programs also receive a substantial snack.

But in April, the Trump administration froze funding for school meals over its legal battle with the state. Maine prevailed in the litigation, and funds were restored. Still, the incident created a sense that the administration’s threats can quickly become reality.

“There’s certainly a fear, and it comes up frequently in conversations with community members. For example, ‘What are you going to do if this is cut, or that is cut?’ ” says Moody.

School mental health services have been similarly at risk in Maine and across the country.

Catharine Biddle, who studies rural education at the University of Maine, says families in the state frequently encounter long waitlists for private mental health services for their children. Trained school clinicians can often meet students’ needs faster, and at no cost to families.

“So schools are this really, really important funnel for resources, for families, and they need funds to be able to deliver those services,” Biddle says.

MSAD 54 was able to hire three licensed counselors after the federal government began sending grant money to schools for mental health services through the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act.

Jordan Chighali is one of those counselors.

“We’re seeing a lot of anxiety, more depression, parents maybe struggling with substance use,” she says. Some of her students don’t have heat at home, or live in campers.

Chighali says getting mental health support at school is often the only option for her students, and many tell her it helps them do better in class.

Around the same time the legal case over USDA school meal funding came to a close this month, the administration announced it would cut $1 billion in mental health grants for schools. For MSAD 54, the funds will run out this December, a year and a half sooner than they had planned for.

“I was disappointed, and just devastated for the kids, honestly,” Chighali says.

Superintendent Jonathan Moody says counseling services are too important to cut staff positions, so he’ll find the money elsewhere. In the meantime, counselors like Chighali will likely have to reduce the number of students they can see.

Despite recent developments, Moody remains optimistic that the federal cuts won’t continue.

“Federal funding of education is an investment worth making. It changes lives,” he says. “It absolutely is essential.”

Radio story edited by: Steve Drummond and Lauren Migaki

Digital story edited by: Nicole Cohen

Radio story produced by: Janet Woojeong Lee

Visual design and development by: Mhari Shaw

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

A political battle between the Trump administration and Maine Governor Janet Mills is targeting public school funding. The administration has threatened to pull millions of dollars in federal money because Maine does not ban transgender athletes from school sports. That has left education leaders across the state anxious about what they will do if the money goes away. NPR’s Jonaki Mehta went to a rural district in Maine where federal dollars play a big role in students’ lives all day long.

BARBARA WELCH: Hi, Mia Martin (ph). Happy Monday, Monday.

JONAKI MEHTA, BYLINE: Around 7:30 in the morning, the students of Mill Stream Elementary jump off of buses and roll into the front doors of their schools.

WELCH: Are you excited about being back at school today?

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #1: Yes, yes.

WELCH: I am. Boy, oh, boy. I got…

MEHTA: Longtime educator, Barbara Welch, greets the students, many who make a sharp left for the cafeteria.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: Cinnamon toast, you got it. There you go. Good morning.

MEHTA: Breakfast is one of at least two free meals kids get here at Mill Stream, which is essential in a community where about two-thirds of the families struggle with poverty.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #2: At home, I ate already cereal, but it doesn’t really fill me up, so I ate a little more.

MEHTA: I’m glad you came for breakfast this morning. Fill those bellies.

Recently, the Trump administration froze money for school meals in Maine over a fight with its governor. The money was eventually restored, but that experience has made the administration’s other threat to pull all federal funding from schools feel real for educators like Barbara Welch.

WELCH: Our district would be devastated if we did not have these funds because they support a wide variety of different programming.

MEHTA: In this district, federal money made up for a little more than 11% of the budget last year, but it plays an outsized role at the elementary schools in the Skowhegan area, including Mill Stream. They all receive Title I money. That’s the biggest grant public schools get from the federal government. Nationwide, about 18 billion Title I dollars went to school serving low-income students last year.

JONATHAN MOODY: Our title program and our federal funds impact our most needy students. They’re the backbone of our intervention systems. They help students get on pace.

MEHTA: The district superintendent, Jonathan Moody, says that’s the whole idea behind Title I, to close the achievement gap between lower-income students and their peers. The students in this rural area come from six surrounding towns, many traveling for miles without hitting a traffic light. Moody says the school provides more than an education.

MOODY: Our hope is that the school is the hub of the district. And I think for rural communities, especially, you see that schools do become the hub.

MEHTA: So to see what he means, we took a tour of Mill Stream Elementary, from arrival until dismissal at 2:15, to see the role federal dollars play in a single school day. After breakfast, we head to a kindergarten classroom near the back of the school.

WELCH: What do you think he says?

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #3: Go.

WELCH: That’s going to have a long I sound because we see this E here at the end. It’s going to…

MEHTA: Our tour guide, Barbara Welch, wears a lot of hats, but her day often includes giving extra support to students in the classroom.

WELCH: Yeah.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #3: Go. Nice. Go.

MEHTA: That’s the kind of work Title I makes possible because Welch’s salary is entirely paid for by that grant. In fact, 74 positions in the district are funded by federal dollars. Like the teaching assistant in the hallway, right outside the kindergarten classroom, working with a student on math, one on one.

WELCH: You’re going to see here in the hallway, this is a kindergartener who has been identified as just needing a little bit more support.

UNIDENTIFIED TEACHING ASSISTANT: How many do we have now?

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #4: One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine.

UNIDENTIFIED TEACHING ASSISTANT: Nine.

WELCH: And with that little extra support, we’re in hopes that we can kind of close the little bit of gap that we see.

MEHTA: Go up the stairs, at the end of that hallway, where a licensed counselor sees dozens of students each week, including fifth-grader Rowen (ph).

ROWEN: I come in here because sometimes I need a counselor because of something that I’m struggling with.

MEHTA: Rowen’s been getting counseling for two years, so we’re not using his full name because he’s a minor and because of student privacy laws related to mental health.

ROWEN: Kids having a counselor is good because they have someone to talk to them, and what’s bugging them in life. And…

MEHTA: But the service will soon be limited because the Trump administration has announced cuts to school mental health grants.

Right next door to counseling, Rowen also gets special education support, which is also made possible largely because of another stream of federal money.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #5: OK, let’s start reading.

UNIDENTIFIED READING INTERVENTIONIST: OK (laughter).

MEHTA: Before lunchtime, we head downstairs and around a corner, where two reading interventionists are at work with first-graders who get pulled out of class for intensive reading and writing instruction.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #5: Cow and sheep looked in the pig pen.

UNIDENTIFIED READING INTERVENTIONIST: Nice job. That’s a big word for us.

ROXANNE DAVIS: Say saw without the sss.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #6: Aw.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #6: Aw.

DAVIS: On.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #6: On. Fawn was…

MEHTA: Reading interventionist Roxanne Davis says these are some of the first-graders struggling most with reading.

DAVIS: This is the most important time for them. If they don’t read now, they will always have difficulty. We give them a chance to come out of that hole.

MEHTA: That approach of concentrating Title I dollars on younger students seems to be working because data from the last three years shows that by the time Mill Stream students get to third grade, they don’t need the extra academic support.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #6: Hid-den. Hidden.

DAVIS: You are rocking it.

MEHTA: Much of the staff across the district – interventionists, teaching assistants, licensed counselors, meal coordinators – all these jobs are made possible by federal dollars. And Roxanne Davis says everyone at Mill Stream is worried what could happen if those jobs were affected by cuts.

DAVIS: They’re very, very nervous about it. If we were not here, those kids that we work with would not be where they are. Without the funding, the program would be lost, and those kids would be lost.

MEHTA: Superintendent Jonathan Moody says he could try to raise the money locally, but that’s really hard in a community struggling with poverty. So, for now, he says he has no choice but to plan as if federal funds will keep flowing.

MOODY: And I think cooler heads will prevail, but I’m an optimist. I’m an educator.

MEHTA: For the time being, the kids here are still receiving these services. They seem blissfully unaware that they’re at the center of a legal and political fight.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: Aubrey Riley (ph).

MEHTA: Around 2:15, as the school day comes to a close, students rush out the doors of Mill Stream to the playground.

How was school? How was your day today?

MIA MARTIN: Good.

MEHTA: But second-grader Mia Martin isn’t eager to leave just yet. School is kind of her whole world.

MIA: Basically home for me.

MEHTA: What do you mean? Is school home for you?

MIA: Pretty much. If I had a bedroom here, it would probably be the office.

MEHTA: She says her favorite part of the day was sitting down to do what she loves most.

MIA: Reading “Green Eggs And Ham.” My favorite book.

MEHTA: Jonaki Mehta, NPR News, Skowhegan, Maine.

(SOUNDBITE OF CLEVER GIRL’S “ELM”)

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.

Sunday Puzzle: TransformeR

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with listener Joan Suits and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Danish military evacuates US submariner who needed urgent medical care off Greenland

Denmark's military says its arctic command forces evacuated a crew member of a U.S. submarine off the coast of Greenland for urgent medical treatment.

Only a fraction of House seats are competitive. Redistricting is driving that lower

Primary voters in a small number of districts play an outsized role in deciding who wins Congress. The Trump-initiated mid-decade redistricting is driving that number of competitive seats even lower.