This Harlem pastor fights mental health stigma — and shares his own struggles

If you or someone you love is experiencing a crisis, call, text or chat 988 for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

It was his own mental health crisis that helped Michael A. Walrond, Jr. to understand and embrace mental health care. “Out of nowhere, I had a suicidal ideation,” Walrond recalls. He was in his late 30s at the time, already busy building a life and expanding his congregation at First Corinthian Baptist in Harlem, New York.

His Masters of Divinity degree hadn’t involved much training in clinical mental health care, and the subject was not a part of his family life growing up in New York City. “I grew up in a traditional West Indian Caribbean household,” he says. “It definitely wasn’t talked about.”

Suicidal ideation — thoughts of dying by suicide — can be a sign of serious mental illness, and Walrond had not realized at the time that he was dealing with depression and anxiety. Research shows clergy suffer from high rates of burnout and often struggle with thoughts of suicide and self-harm. After his own suicidal ideation, Walrond immediately pursued mental health care.

He now credits therapy with saving his life.

Walrond wondered how many others in his community were suffering in silence. “ I think in the African American community, historically, there’s been the normalization of trauma,” he says. “You don’t really see the mental health impact.”

Today, Walrond is battling stigma around mental health in his profession, his community and his congregation — and leading by example.

Bringing mental health care into the church

At first, Walrond hired one, part-time therapist to work at First Corinthian. He stands in the church — which he has built over 20 years into a congregation of thousands — and gestures at the small office where his first therapist worked, “she was in this office.” He hired her on a hunch that people would use her services, but he hadn’t anticipated just how much demand there would be. He recalls her telling him, “Pastor — a lot of people are coming.”

Walrond noticed something else — that people were often sheepishly making their way to the therapist’s office, embarrassed to admit their purpose. He decided he needed to expand to a place where people felt comfortable coming.

Today, the church runs a separate nonprofit, called H.O.P.E. Center, funded through grants and congregation donations. Lena Green, the executive director of the center, opens the door to the clinic, in a separate building around the corner from the church. “We currently have seven clinicians on staff: three doctors, one psychiatrist, three social workers, one psychologist,” explains Green, who has a doctorate in social work.

Green says they’ve made progress in the years since they’ve grown this mental health hub, but there is still widespread stigma in the community. In recent years, Black teens and adolescents especially have seen an increase in mental health crises, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Approaching this subject can be difficult.

For a lot of families, there’s sort of what I like to call the conspiracy of silence,” says Green. “Like we know this thing happened, but we shouldn’t be talking about it publicly. But we know we need to get help.”

Green and Walrond say they saw a unique opportunity in folding clinical health services into church. It is already a place where people feel they can bring their mental suffering.

But they are still constantly battling stigma around the idea of pursuing mental health treatment. Walrond says he tries to disabuse people of the idea that asking God for help is the only way to pursue mental well-being. “You can trust God and go see a doctor to get medication for high blood pressure,” he says. “When it comes to mental health issues, all of a sudden there’s a problem with that.”

“ My generation, you know, my parents’ generation — if you are talking to a therapist, if you’re getting help, you are broken,” says Marchelle Green-Dorvil, a congregant at First Corinthian. Green-Dorvil’s son, Gabriel, participates in a youth group for teens at the church aimed at reducing suicide risk. She credits the group with helping their whole family through a difficult time. But she says some still assume that people who are pursuing treatment are weak. “There’s something wrong, right?”

And yet, she says, church has always been held as sacred ground for revealing vulnerabilities. The message from the previous generation, she says, is that “If there’s any sharing, it should be done only in a church setting.” The work at First Corinthian Baptist is to show people that therapeutic spaces are also safe.

Bringing suicide into the open

One of Walrond’s strategies is to talk openly about suicide and mental health, and to dare others to do the same. That includes his services. In a video from a service a few years ago, he says to the congregation, “ I’ve known of moments when there were people who went to church, left church and then experienced death by suicide.”

People are swaying and crying, holding each other. Walrond encourages congregation members to do something courageous — to stand up to come to the front of the sanctuary — if they could relate. “Those who are tired of life, and you’re at that point where you’re almost ready to give up today — I want you to come,” he says to them. “I want you to make your way today.”

Remarkably, people made their way to the front.

In preparing services like these, Walrond says he looks to scripture, among other places, for guidance. “You have several people in scripture who wanted to die because of the weight of the responsibility and the expectations. No different,” he explains. “Elijah — who was a prophet — he asked God to take his life. It was Moses who asked God to kill him.”

He believes that there’s no difference between spiritual needs and physical needs, including mental health. “Part of the responsibility,” says Walrond “is to treat the needs of the people as holy.”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 9-8-8 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

A large part of any pastor’s job is to offer emotional support through things like rituals, empathy, prayer. But there can still be stigma in churches around clinical mental health care. NPR’s Katia Riddle brings us this profile of one pastor in Harlem who is battling stigma within his congregation and leading by example. And a caution, this story discusses suicide.

KATIA RIDDLE, BYLINE: Mental health was not something that Michael Walrond thought about much as a kid.

MICHAEL WALROND: And I grew up in, you know, a traditional West Indian Caribbean household. It definitely wasn’t talked about.

RIDDLE: As an adult, he committed to a life of service and became a pastor. He got a master’s of divinity degree, but he didn’t get much explicit training around mental health. Then, in his late 30s, he found himself in a crisis.

WALROND: I had an experience out of nowhere where I had a suicidal ideation.

RIDDLE: Suicidal ideation is a kind of fantasy about dying by suicide. It can be an indicator of a serious illness.

WALROND: I didn’t realize I was dealing with depression and anxiety.

RIDDLE: Research shows pastors have a disproportionate amount of these kinds of mental health issues. But Walrond says there’s a stigma around talking about this occupational hazard. After his crisis, Walrond started going to therapy. He says it saved his life.

WALROND: And I remember realizing that, you know what? If this has been such a critical impact on my life, I know other people may be suffering in silence.

RIDDLE: His church is First Corinthian Baptist in Harlem. There are thousands of people in his congregation. It’s a busy community hub all week, not just Sundays. On this morning, he stands outside a door upstairs. That is where his first part-time therapist worked years ago.

WALROND: Yeah, she was here. And she was the first one – when she was a pastor, there was a lot of people who were coming.

RIDDLE: At the time he didn’t know of any other churches that were hiring licensed clinicians. It’s still rare. But he says once he started looking for it, he saw the need everywhere.

WALROND: I think in an African American community, historically, there’s been the normalization of trauma, right? So if you normalize trauma, then you don’t really see the mental health impact of trauma.

RIDDLE: Now the church has a separate nonprofit to provide therapy. It’s around the corner.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

RIDDLE: Throughout the office, staff play this music. It helps with confidentiality in their tight quarters. Lena Green is the executive director of this program.

LENA GREEN: So we currently have seven clinicians on staff. We have one, two, three – we have three doctors, one psychiatrist, three social workers, one psychologist.

RIDDLE: It’s funded through grants and church donations. Green says they’re making progress, but stigma is something they’re still battling. In recent years, Black teens and adolescents, especially, have seen an increase in mental health crises like suicide and suicide ideation.

GREEN: Because for a lot of families, there’s sort of what I like to call, the conspiracy of silence, right? Like, we know this thing happened, but, you know, we shouldn’t be talking about it publicly. But we know we need to get help.

RIDDLE: Part of combating this stigma and encouraging people to use these services is bringing mental health struggles out into the open. This recording is from a church service a couple of years ago with Pastor Walrond.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

WALROND: I’ve known of moments when there were people who went to church – this is true – left church and then experienced death by suicide.

RIDDLE: People are swaying and crying, holding each other at this service. Walrond encourages congregation members to do something courageous – to stand up, to come to the front of the sanctuary if they could relate.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

WALROND: Those who are tired of life, and you’re at that point where you’re almost ready to give up today, I want you to come. I want you to make your way today.

(APPLAUSE)

RIDDLE: Walrond says he looks to scripture for guidance on this topic.

WALROND: Elijah, who was a prophet, he asked God to take his life. It was Moses at the time who asked God to kill him. Like, you have several people in Scripture who wanted to die because of the weight of the responsibility and the expectations. No different.

RIDDLE: He says physical needs are spiritual needs.

WALROND: Part of the responsibility is to treat the needs of the people as holy.

RIDDLE: Which means, says Pastor Michael Walrond, that mental health is holy.

Katia Riddle, NPR News, Harlem.

SIMON: And if you or someone you know is in crisis, you can call or text 988 – just those three numbers – 9-8-8 – for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

High-speed trains collide after one derails in southern Spain, killing at least 21

The crash happened in Spain's Andalusia province. Officials fear the death toll may rise.

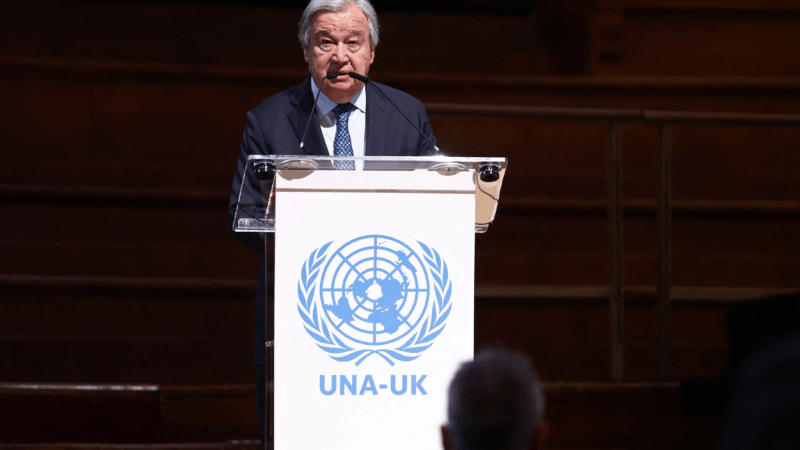

United Nations leaders bemoan global turmoil as the General Assembly turns 80

On Saturday, the UNGA celebrated its 80th birthday in London. Speakers including U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres addressed global uncertainty during the second term of President Trump.

Parts of Florida receive rare snowfall as freezing temperatures linger

Snow has fallen in Florida for the second year in a row.

European leaders warn Trump’s Greenland tariffs threaten ‘dangerous downward spiral’

In a joint statement, leaders of eight countries said they stand in "full solidarity" with Denmark and Greenland. Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen added: "Europe will not be blackmailed."

Syrian government announces a ceasefire with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces

Syria's new leaders, since toppling Bashar Assad in December 2024, have struggled to assert their full authority over the war-torn country.

U.S. military troops on standby for possible deployment to Minnesota

The move comes after President Trump again threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to control ongoing protests over the immigration enforcement surge in Minneapolis.