These brain implants speak your mind — even when you don’t want to

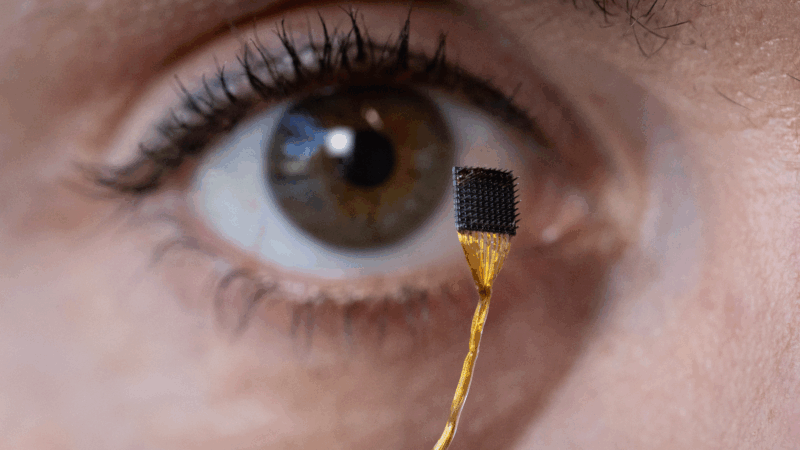

Surgically implanted devices that allow paralyzed people to speak can also eavesdrop on their inner monologue.

That’s the conclusion of a study of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) in the journal Cell.

The finding could lead to BCIs that allow paralyzed users to produce synthesized speech more quickly and with less effort.

But the idea that new technology can decode a person’s inner voice is “unsettling,” says Nita Farahany, a professor of law and philosophy at Duke University and author of the book: The Battle for Your Brain.

“The more we push this research forward, the more transparent our brains become,” Farahany says, adding that measures to protect people’s mental privacy are lagging behind technology that decodes signals in the brain.

From brain signal to speech

BCI’s are able to decode speech using tiny electrode arrays that monitor activity in the brain’s motor cortex, which controls the muscles involved in speaking. Until now, those devices have relied on signals produced when a paralyzed person is actively trying to speak a word or sentence.

“We’re recording the signals as they’re attempting to speak and translating those neural signals into the words that they’re trying to say,” says Erin Kunz, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University’s Neural Prosthetics Translational Laboratory.

Relying on signals produced when a paralyzed person attempts speech makes it easy for that person to mentally zip their lip and avoid oversharing. But it also means they have to make a concerted effort to convey a word or sentence, which can be tiring and time consuming.

So Kunz and a team of scientists set out to find a better way — by studying the brain signals from four people who were already using BCIs to communicate.

The team wanted to know whether they could decode brain signals that are far more subtle than those produced by attempted speech. The team wanted to decode imagined speech.

During attempted speech, a paralyzed person is doing their best to to physically produce understandable spoken words, even though they no longer can. In imagined or inner speech, the individual merely thinks about a word or sentence — perhaps by imagining what it would sound like.

The team found that imagined speech produces signals in the motor cortex that are similar to, but fainter than, those of attempted speech. And with help from artificial intelligence, they were able to translate those fainter signals into words.

“We were able to get up to a 74% accuracy decoding sentences from a 125,000-word vocabulary,” Kunz says.

Decoding a person’s inner speech made communication faster and easier for the participants. But Kunz says the success raised an uncomfortable question: “If inner speech is similar enough to attempted speech, could it unintentionally leak out when someone is using a BCI?”

Their research suggested it could, in certain circumstances, like when a person was silently recalling a sequence of directions.

Password protection?

So the team tried two strategies to protect BCI users’ privacy.

First, they programmed the device to ignore inner speech signals. That worked, but took away the speed and ease associated with decoding inner speech.

So Kunz says the team borrowed an approach used by virtual assistants like Alexa and Siri, which wake up only when they hear a specific phrase.

“We picked Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, because it doesn’t occur too frequently in conversations and it’s highly identifiable,” Kunz says.

That allowed participants to control when their inner speech could be decoded.

But the safeguards tried in the study “assume that we can control our thinking in ways that may not actually match how our minds work,” Farahany says.

For example, Farahany says, participants in the study couldn’t prevent the BCI from decoding the numbers they were thinking about, even though they did not intend to share them.

That suggests “the boundary between public and private thought may be blurrier than we assume,” Farahany says.

Privacy concerns are less of an issue with surgically implanted BCIs, which are well understood by users and will be regulated by the Food and Drug Administration when they reach the market. But that sort of education and regulation may not extend to upcoming consumer BCIs, which will probably be worn as caps and used for activities like playing video games.

Early consumer devices won’t be sensitive enough to detect words the way implanted devices do, Farahany says. But the new study suggests that capability could be added someday.

If so, Farahany says, companies like Apple, Amazon, Google and Meta might be able to find out what’s going on in a consumer’s mind, even if that person doesn’t intend to share the information.

“We have to recognize that this new era of brain transparency really is an entirely new frontier for us,” Farahany says.

But it’s encouraging, she says, that scientists are already thinking about ways to help people keep their private thoughts private.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

A person can bite their tongue to avoid blurting out a secret, but a surgically implanted brain computer interface can reveal words that were never meant to be spoken. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports on a new study that looks at the privacy concerns raised by technology that decodes signals in the brain.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: Brain computer interfaces, or BCIs, are experimental devices that can restore a paralyzed person’s ability to speak. Erin Kunz of Stanford University says these implanted devices monitor the brain’s motor cortex, which controls the muscles involved in speech.

ERIN KUNZ: We’re recording the signals as they’re attempting to speak and translating those neural signals into the words that they’re trying to say.

HAMILTON: Either on screen or with a synthesized voice. Relying on signals produced when a paralyzed person attempts speech makes it easy for them to mentally zip their lip and avoid oversharing. But it also means that person has to make a concerted effort to convey a word or sentence. That’s tiring and time consuming. So Kunz and a team set out to find a better way with help from four people already using BCIs.

KUNZ: The first thing we did was looked at individual words, both when they’re attempting to speak as well as when they’re imagining to speak and even when they were listening or reading.

HAMILTON: The team found a lot of overlap between intended speech and imagined speech. Eventually, they were able to decode words and sentences that existed only in a person’s imagination.

KUNZ: We were able to get up to 74% accuracy decoding sentences from a 125,000-word vocabulary.

HAMILTON: That made communication faster and easier for the participants, but Kunz says the success also raised a question.

KUNZ: If inner speech is similar enough to attempted speech, could it accidentally leak out when someone is using a BCI?

HAMILTON: It could, so the team tried two strategies to protect BCI users’ privacy. One was to program the device to ignore inner speech signals. That worked, but took away the speed and ease of decoding imagined words. So Kunz says the team borrowed an approach used by virtual assistants like Alexa and Siri, which wake up only when they hear a specific phrase.

KUNZ: We picked chitty chitty bang bang ’cause it doesn’t occur too frequently in typical conversations, I would guess, and it’s highly identifiable, highly decodable.

HAMILTON: That allowed participants to control when their inner speech was being decoded. The study, which appears in the journal Cell, adds to an ongoing discussion about privacy and new technologies that decode a person’s brain activity. Nita Farahany of Duke University wrote a book on the subject called “The Battle For Your Brain.” She says the two privacy safeguards used in the study are a step in the right direction.

NITA FARAHANY: But these both assume that we can control our thinking in ways that may not actually match how our minds work.

HAMILTON: For example, Farahany says participants in the study couldn’t always control their inner voice.

FARAHANY: They had this counting task, and during that counting task, the BCI did pick up numbers people were thinking, which means that the boundary between private and public thought may be blurrier than we assume.

HAMILTON: Farahany says surgically implanted BCIs will be regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which could require privacy protections. But that sort of regulation may not extend to consumer BCIs, worn as caps and used to do things like play video games. Farahany says the new study suggests that someday, those consumer devices may also be able to detect unspoken words.

FARAHANY: What this research shows is something unsettling, right? The brain patterns for thinking words and speaking them are remarkably similar.

HAMILTON: Farahany says that could allow companies like Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook to find out what’s going on in a consumer’s mind even if that person doesn’t intend to share.

FARAHANY: The more we push this research forward, the more transparent our brains become, and we have to recognize that this era of brain transparency really is an entirely new frontier for us.

HAMILTON: Farahany says she’s encouraged, though, that researchers are already looking for ways to help people protect their mental privacy.

Jon Hamilton NPR News.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.

The Live Nation trial could reshape the music industry. Here’s what you need to know

On Tuesday opening statements will begin for the federal antitrust trial against Live Nation, one of the largest entertainment companies in the world.

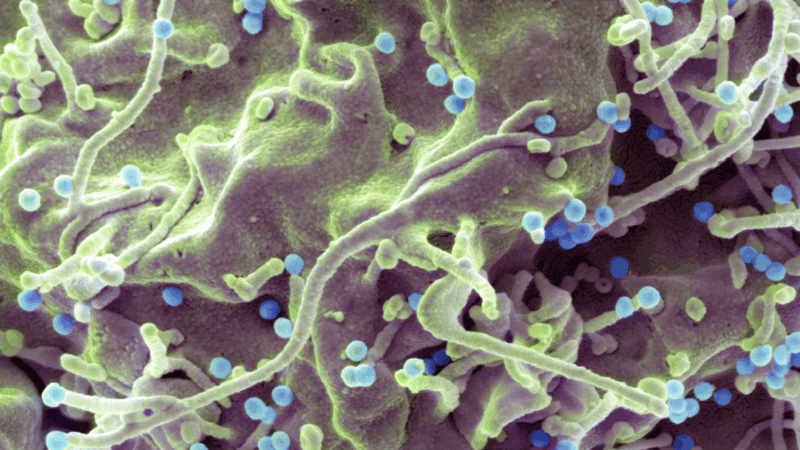

A new one-a-day-pill holds promise for HIV’s ‘forgotten population’

It's designed to take the place of complicated, multiple drug regimens that many people with HIV need to follow. And it's also beneficial because the HIV virus is always evolving.

For filmmaker Chloé Zhao, creative life was never linear

Director Chloé Zhao used meditation, somatic exercises and dance to inspire the cast and crew of this Oscar-nominated story about William Shakespeare's family.

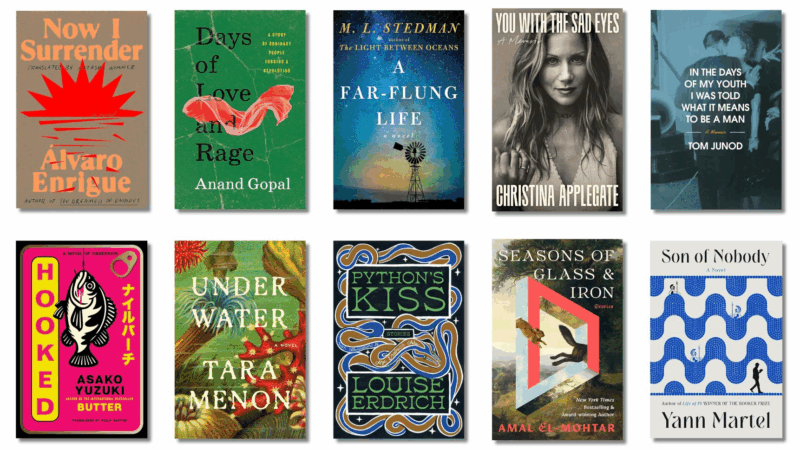

10 new books in March offer mental vacations

March is always a big one for books – this year is no different. We call out a handful of upcoming titles for readers to put on their radars — offering a good alternative to doomscrolling.

Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., talks about the war with Iran and upcoming war powers vote

NPR's A Martínez asks Delaware Democrat Chris Coons, a member of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, about the war with Iran.