The world’s oldest and largest iceberg will soon be no more

It’s been a long and unusual journey for the world’s largest iceberg, known as A23a, but it’s ending in a relatively usual way: breaking apart and melting in the warmer waters of the South Atlantic Ocean, just like icebergs have done for millions of years before.

The iceberg — which at one time was around the same size as the Hawaiian island of Oahu — is “rapidly breaking up” into several “very large chunks,” according to scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), which has been tracking its movements.

A23a has been closely tracked by scientists ever since it broke off, or calved, from the Filchner-Ronne ice shelf in Antarctica in 1986. It’s had the title of “largest iceberg” several times since then — sometimes overtaken by larger but shorter-lived icebergs, but regaining it when those broke apart.

It’s also the oldest current iceberg, having managed to slow its natural demise by getting stuck not once, but twice, after calving from its parent-berg, meaning it managed to hang out in colder waters for longer than most.

But now, at nearly 40 years old, it seems to be reaching the end of its journey.

“The iceberg is rapidly breaking up, and shedding very large chunks, themselves designated large icebergs by the U.S. national ice centre that tracks these,” Andrew Meijers, an oceanographer at BAS, told NPR in an email on Thursday.

It’s now shrunk to about 1,700 square kilometers (656 square miles), or roughly the size of Greater London, Meijers says.

“It’s drifted so far north, it’s in a place where icebergs this size can’t survive,” says Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder specializing in the polar regions.

Scambos says this is part of the normal life cycle of icebergs, something that’s been happening for millennia, and doesn’t appear to be part of climate change.

“It’s really quite typical and normal. It is kind of a big, spectacular thing that our planet does as part of day-to-day operations,” he says.

What hasn’t been normal has been A23a’s path to get to this point. It was grounded for decades in the seafloor of the Weddell Sea, after almost immediately getting stuck to a sandbank in shallow waters after it broke away in the 1980s. It finally freed itself in 2020 and started heading to the open ocean in late 2023.

But then, in August of 2024, it got stuck — again — this time slowly twirling in a kind of ocean vortex known as the Taylor column.

There it stayed, whimsically spinning in satellite images for months before it broke free yet again late last year, carried by the strong current north. In one final act of drama, A23a appeared as if it might hit the island of South Georgia earlier this year, threatening the seal and penguin colonies there, but grounded about 50 miles off the coast of the island by March.

Meijers at BAS says that now A23a is in water that is well above freezing, meaning it will break apart quickly in the coming weeks.

“This, plus moving ever further north and the coming of southern spring means it is likely to rapidly disintegrate into bergs too small to track further,” he says.

Eventually, it will be too small to be seen by satellite — the end of a decades-long era for the scientists who have tracked it.

But even in its demise, A23a will continue to help scientists have a better understanding of enormous icebergs and how they impact the environment around them.

Earlier this year, samples were taken from the environments touched by A23a’s path, which will give insight into the life that could come in its wake as fresh water mixes with salt water, and the impact it could have on carbon levels in the ocean, according to scientists at BAS.

Scambos at the University of Colorado Boulder says research like that can help contribute to science that will hopefully have an impact far into the future.

“It’s another opportunity to understand some of the processes that govern those mega glaciers,” he says. “And in fact, those are very important in terms of controlling sea level rise in the long term, decades to centuries from now.”

Four top U.S. speedskaters to watch at the Olympics

U.S. speed skaters set to compete in Milan are drawing comparisons to past greats like Eric Heiden, Bonnie Blair, and Apolo Ohno. Here are four to watch in the 2026 Winter Olympic Games.

A ‘Shark Tank’ alum needed cash to pay tariffs. This shadowy lending world was ready

How about $350,000 within hours? The pitches flood small businesses: "No hidden fees, No BS." These financial lifelines are barely regulated and can turn into trip wires.

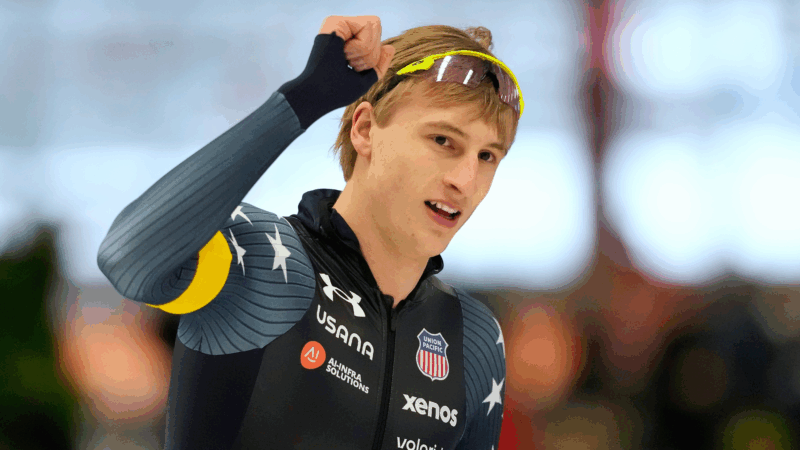

U.S. skater Connor McDermott-Mostowy joins record number of out LGBTQ Winter Olympians

When U.S. speedskater Connor McDermott-Mostowy makes his Winter Olympic debut in Milan, he'll join a record number of out LGBTQ athletes. But of the 46 out athletes, only 11 are men.

5 glaring warning signs for Republicans in this year’s midterm elections

Here's why Republicans are facing an uphill battle, particularly for retaining control of the House.

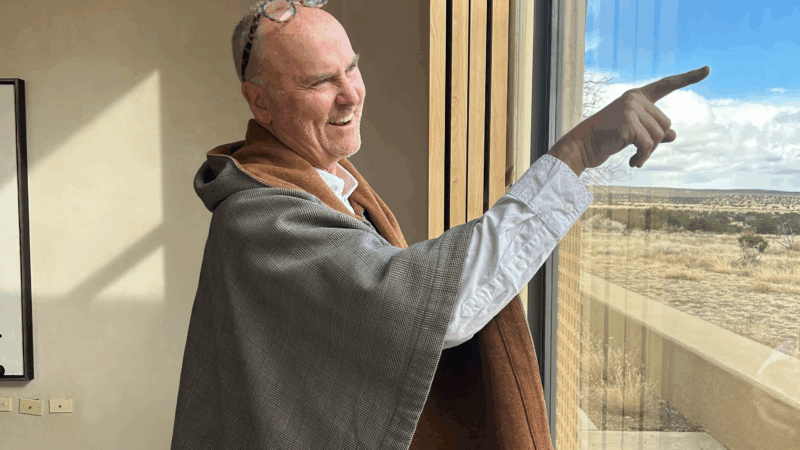

Need a new path in midlife? There’s a school for that and a quiz to kickstart it

Schools across the country are offering courses and retreats for people 50+ who want to reinvent themselves and embrace lifelong learning and discovery.

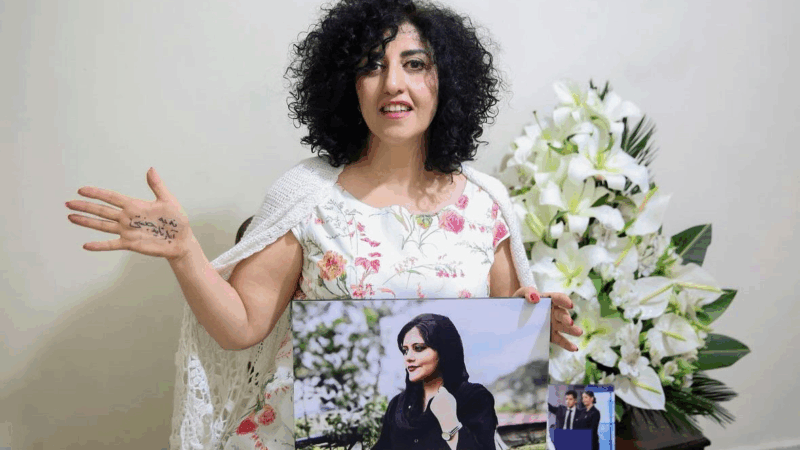

Crackdown on dissent after nationwide protests in Iran widens to ensnare reformist figures

Detained Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi has received another prison sentence of over seven years.