The world now has its first ever pandemic treaty. Will it make a difference?

Member states of the World Health Organization voted overwhelmingly to adopt the first ever pandemic agreement, a treaty aimed at preventing, preparing for and responding to any future pandemic. After three years of tough negotiations, no country voted against the agreement at WHO’s annual meeting. (The United States did not attend this meeting because of President Trump’s intent to withdraw from WHO membership.)

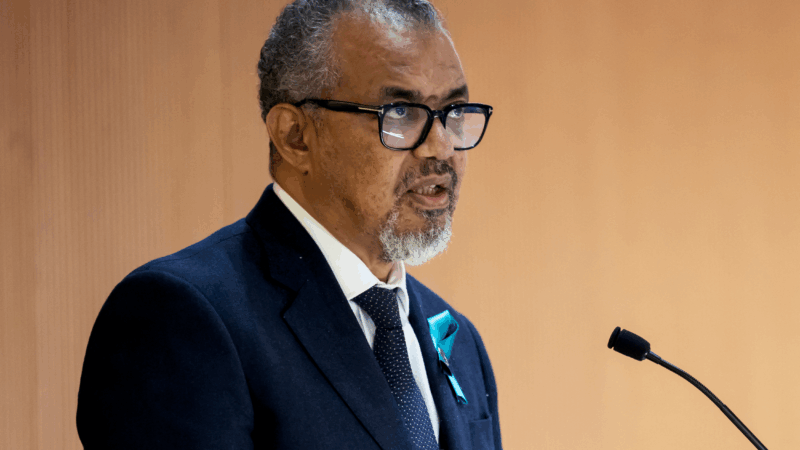

“The world is safer today thanks to the leadership, collaboration and commitment of our Member States to adopt the historic WHO Pandemic Agreement,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, after the vote.

“The Agreement is a victory for public health, science and multilateral action. It will ensure we, collectively, can better protect the world from future pandemic threats. It is also a recognition by the international community that our citizens, societies and economies must not be left vulnerable to again suffer losses like those endured during COVID-19.”

The 30-page treaty lays out a framework for preventing pandemics from even starting — by boosting surveillance of animals to lower risk of viruses spilling over to humans — as well as responding more effectively once pandemics do come, for example by providing protective equipment to health care workers and aligning regulatory systems to help expand access to treatments.

Yet the agreement’s ultimate impact remains unclear, especially since it lacks enforcement mechanisms and robust funding. President Trump’s planned withdrawal from WHO means the U.S. — which helped draft the treaty and is historically the biggest WHO funder — is not part of it, which could further weaken its power.

Additionally, countries kicked the can on sorting out the most contentious details. Over the next year, delegates must decide how wealthy countries will share tests, vaccines, treatments — and the technology behind them — with lower income countries in exchange for the data required to develop those interventions, including genetic sequencing of pathogens. The agreement outlines a goal of having pharmaceutical companies donate or make more affordable 20% of the pandemic products they produce.

Before the treat goes into effect, 60 countries must ratify the agreement internally — an in-country vote. That’s a process that could drag on for over a year. But even with those uncertainties, many health officials praised the agreement.

“It is a huge milestone, and the beginning of a longer process that is really about building those capacities, and building trust and cooperation,” said Alexandra Phelan, a global health lawyer at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “You don’t want to put too much weight on a document, essentially, but for me it’s a bit of a glimmer in the darkness. We should take hope from the fact that countries didn’t abandon this process when there were many opportunities for them to do so.”

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

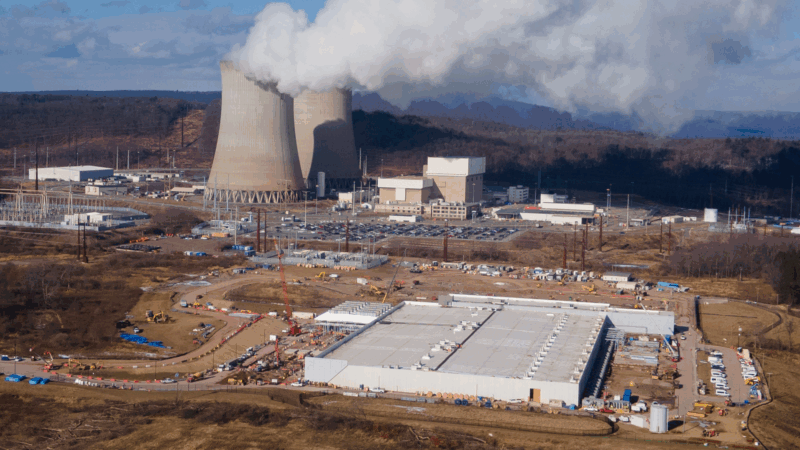

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.