The U.S. set the global order after WWII. Trump has other plans

From the ashes of World War II, President Harry Truman presided over the creation of global institutions that have defined the international order for the past 80 years.

“It must be a policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressure,” Truman said as he spelled out his doctrine in a 1947 speech to Congress.

In a few short years, the U.S. helped establish and lead the United Nations, NATO, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The U.S. helped rebuild Europe with assistance funneled through the Marshall Plan, and also funded the reconstruction of Japan.

Democratic and Republican presidents supported these institutions for generations. They sometimes grumbled at the cost, yet believed they ultimately strengthened the U.S. as the world’s leading superpower.

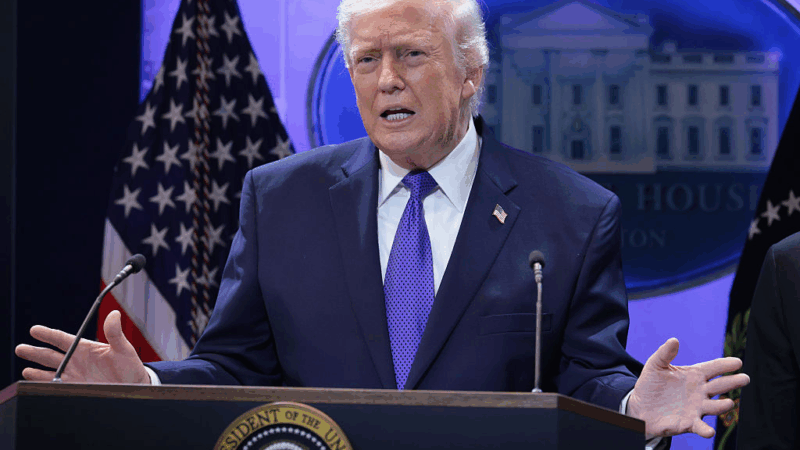

But 100 days into his second term, Donald Trump is moving aggressively to scale back the U.S.’s role in the world, based on his “America First” agenda. Trump sees this web of alliances, treaties and soft power as expensive, outdated relics that restrain America’s ability to act decisively on its own.

“I’m not aligned with anybody. I’m aligned with the United States of America, and for the good of the world,” Trump said in February.

Trump says the U.S. should not be the world’s policeman and should not guarantee the security of its allies. Rather, he has attacked many of them and threatened to take control of territory ranging from Greenland to Canada to the Panama Canal to the Gaza Strip.

Hal Brands, a historian at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative Washington think tank, puts it this way: “If I had to boil it all down, I would say Trump’s goal is to extract more privileges from the international order while bearing fewer responsibilities for upholding them.”

Trump scaled back U.S. global commitments in his first term. In his second term, he’s launched a much more ambitious effort.

“In the first term, I would say the defining characteristic of this foreign policy was chaos. This time he’s really taking a sledgehammer approach to U.S. foreign policy and the institutions around it,” said Kelly Grieco with the Stimson Center, a nonpartisan think tank.

Trump wants to do this on all major fronts — military, diplomatic and economic.

Scaling back military commitments

With the U.S. military, Trump wants to end U.S. involvement in open-ended wars, like the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

His signature moment so far was the White House meeting two months ago where Trump and Vice President Vance berated Volodymyr Zelenskyy, saying the Ukrainian president had not shown enough gratitude for U.S. aid and was overestimating Ukraine’s military capabilities.

“You’re not in a good position. You don’t have the cards right now,” an agitated Trump said to Zelenskyy. “You’re gambling with the lives of millions of people. You’re gambling with World War III.”

The president opposes further U.S. military assistance for Ukraine and wants a permanent ceasefire. However, this is proving elusive as the fighting grinds on, with Russian leader Vladimir Putin launching some of its largest aerial assaults of the war in recent weeks.

“He’s underestimating, often, his adversaries,” Stewart Patrick, with the nonpartisan Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said of Trump. “He seems to believe that Vladimir Putin is going to be satisfied with only 20% of Ukraine. This is the appetizer course as far as Vladimir Putin is concerned. He wants the entire meal.”

A ceasefire would give Trump some cover to pull back in Ukraine, where the U.S. does not have troops, though it has led the international effort to support that country since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

But if the war carries on and Russia makes further gains, Trump could look weak, unable to stand up to Russia.

This would raise even more questions about NATO’s future and the U.S. willingness to defend Europe.

“I think that NATO will survive a second Trump presidency,” said Brands. “But I don’t think that any European country will want to be as dependent on the United States in the future as they were in the past.”

Diplomatic negotiations, but no breakthroughs

On the diplomatic front, Trump is pursuing several high-stakes deals.

It’s still early in his second term, though so far he’s had no major successes. An Israel-Hamas ceasefire, reached as Trump entered office in January, has collapsed.

Talks with Iran on a nuclear agreement are ongoing.

Kelly Grieco applauds the diplomatic efforts, but is critical about Trump’s approach. He believes that these complex negotiations can be done quickly and with little or no input from allies.

“In many ways he overestimates American power,” said Grieco. “This leads him to this more bullying approach, because he thinks the United States is so powerful that our allies and our adversaries will have to give way.”

This unilateral approach to diplomacy is also evident in Trump’s trade policy. His actual or threatened tariffs against virtually every country have destabilized the global economy, and many economists say this was a significant factor at home as well, where the U.S. economy shrank 0.3% in the first three months of this year.

Trump thinks U.S. economic clout will give him the leverage to win much better terms in one-on-one deals. His main target is China, yet his go-it-alone approach led him to antagonize friendly countries that could help in a collective effort to isolate China.

“If you’re going to be trying to press China on a number of different fronts, you would want to do it with allies,” said Patrick.

Eighty years after the U.S. established the modern global order, foreign policy analysts wage nonstop debates about how it should be updated. The discussion often centers on whether the U.S. is still able and willing to shoulder the burden it has since World War II. But, Hal Brands said, if the U.S. abandons that role, no other country can replace it.

“If the United States says that it’s going to stop being a global public goods provider and simply take benefits out of the system, I don’t know how long that system is going to last,” Brands said.

Trump seems determined to find out.

What NPR reporters will remember most about these Winter Olympics

NPR's reporters on the ground in Italy reflect on a far-flung, jam-packed Winter Olympics.

In the shadow of the Olympics, migrants search for a welcome in Milan

As Italy cracks down on migration, Milan takes a different path — offering shelter and integration to asylum seekers even as the central government tightens borders and funds deterrence abroad.

Trump to raise global tariffs. And, most say the state of the union is weak, poll says

President Trump says he is raising global tariffs to 15%. And ahead of the president's address tomorrow, most Americans say the state of the union is not strong, according to an NPR poll.

U.S. has a quarter fewer immigration judges than it did a year ago. Here’s why

The continued drain of personnel from the already strained immigration court system has contributed to depleted staff morale, mounting case backlogs — and floundering due process.

Poll: Most say the state of the union is not strong and the U.S. is worse off

Ahead of the State of the Union address on Tuesday, evidence continues to mount that President Trump is facing political headwinds.

Influencers are promoting peptides for better health. What’s the science say?

The latest wellness craze involves injecting these molecules for athletic performance, longevity and more. Scientists say the research isn't keeping pace with the health claims.