The U.S. could use ‘bunker buster’ bombs in Iran. Here’s what to know about them

As the escalated conflict between Israel and Iran entered its sixth day, the U.S appears to be increasingly weighing direct military involvement.

“I may do it. I may not do it,” President Trump told reporters on Wednesday. “I mean, nobody knows what I’m going to do.”

Israel says its assault on Iran is necessary to prevent the country from building a nuclear weapon — which it sees as an existential threat. That’s also a common goal for the U.S., which until last week had been in the midst of negotiations with Iran on limiting the country’s nuclear capabilities.

Iran’s most fortified and best-protected nuclear facility, called Fordow, is buried deep inside a mountain. Only the U.S. has the 30,000-pound bombs — often referred to as bunker busters — capable of reaching it, as well as the B-2 stealth bombers needed to deliver them.

That puts Israel — and the U.S. — in a difficult position.

“[Israel] can’t destroy Tehran’s program on their own,” says Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a nonpartisan think tank. “But if they stop and it survives, this will be viewed as a defeat.”

On Tuesday, Trump told reporters aboard Air Force One that he was seeking “a real end” to Iran’s nuclear ambitions, which he called “better than a ceasefire.”

What are “bunker buster” bombs?

The term “bunker buster” is a broad one, used to describe any bomb that is designed to penetrate deep below the surface before exploding. They date back to World War II but were significantly developed during the Gulf War.

Ryan Brobst, a munitions expert at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington think tank that often advocates for Israeli security and is critical of Iran, says a common misconception about bunker busters is that they depend on a large amount of explosives to do their job.

“What actually differentiates them from other weapons is their hardened steel casing,” says Brobst. “They actually often have a smaller explosive payload than other weapons, but it’s the casing that allows them to dig into the ground, kind of like a drill, and then destroy these targets.”

The bomb specifically in question now is the GBU-57 MOP (Massive Ordnance Penetrator), among the heaviest and most powerful nonnuclear bombs in the U.S. arsenal, weighing in at 30,000 pounds and 20 feet long. It has never been used in combat before.

Munitions experts tell NPR that the GBU-57 was more recently developed with Iran’s nuclear facilities — like the mountain-encased Fordow — in mind. But a lot about it is classified, including how deep it can go.

“So if one weapon wasn’t able to penetrate it, what would have to happen is that another weapon would need to be dropped in essentially exactly the same drill hole as the one previous, then drill down further and then explode,” says Brobst, pointing out that this would mean inherently more risk if multiple drops were necessary.

Why can only the U.S. use them?

Because of its size, the GBU-57 has to be dropped from a B-2 stealth bomber, which only the U.S. possesses. Israel does not have heavy bombers capable of carrying such a weapon.

“This isn’t a bomb we can just give the Israeli air force and have them use it,” says Trevor Ball, an associate researcher at Armament Research Services, a munitions analysis firm, and a former U.S. Army explosive ordnance disposal technician.

“There’s no way for Israel to do this strike without the U.S. It’s not as simple as, you know, the U.S. flying a cargo plane over and going, ‘Here you go,'” he says.

Would it work?

Most experts agree that the GBU-57 could cause serious — possibly even irreparable — destruction to a facility like Fordow, even if it took several hits.

“It could cause real damage,” says Miller.

But he says the real question is whether it would be enough to stop Iran’s nuclear program, which is what both Israel and the U.S. say is the main objective: “How do you bomb scientific knowledge out of the head of a scientific community?”

Ali Vaez, director of the International Crisis Group’s Iran Project, says intelligence estimates are that a successful U.S. attack would likely simply set Iran’s nuclear program back by a year or two — not stop it for good.

“The reality is that even if Fordow is fully destroyed, Iran still has the know-how and the capability to reconstitute its nuclear program. So this is not a solution to the nuclear crisis with Iran,” Vaez says.

Could an attack on nuclear sites endanger civilians?

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has confirmed that Iran is producing highly enriched uranium at Fordow, which means a powerful strike on the facility could release radioactive material into the area around it.

The radioactivity would constitute a serious hazard for anyone nearby, but it would be unlikely to travel very far beyond the facility itself. The IAEA says it believes a release has already occurred at Iran’s main nuclear facility in Natanz, which was struck at the outset of fighting.

Speaking late last week, Rafael Mariano Grossi, director-general of the IAEA, called the attacks on nuclear facilities in Iran “deeply concerning.”

“I have repeatedly stated that nuclear facilities must never be attacked, regardless of the context or circumstances, as it could harm both people and the environment,” he said, warning that the consequences of a major attack could go well beyond the boundaries of Iran.

He urged all parties to exercise “maximum restraint.”

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

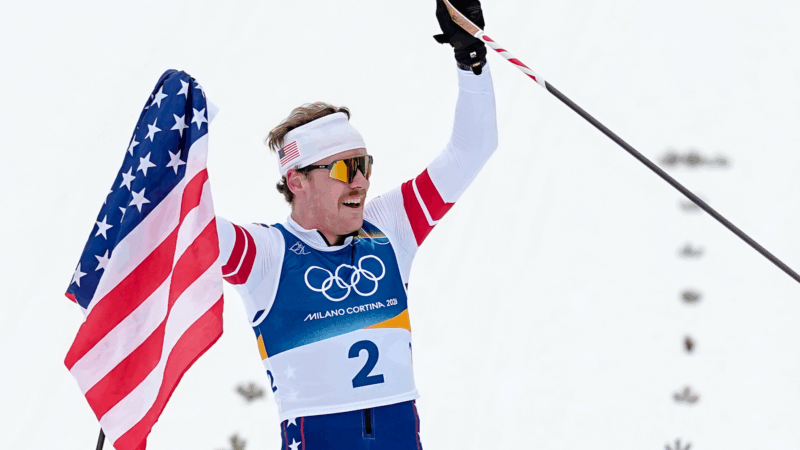

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.

An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine — to play pretend — has long been thought to be unique to humans. A new study suggests one of our closest living relatives can do it too.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.

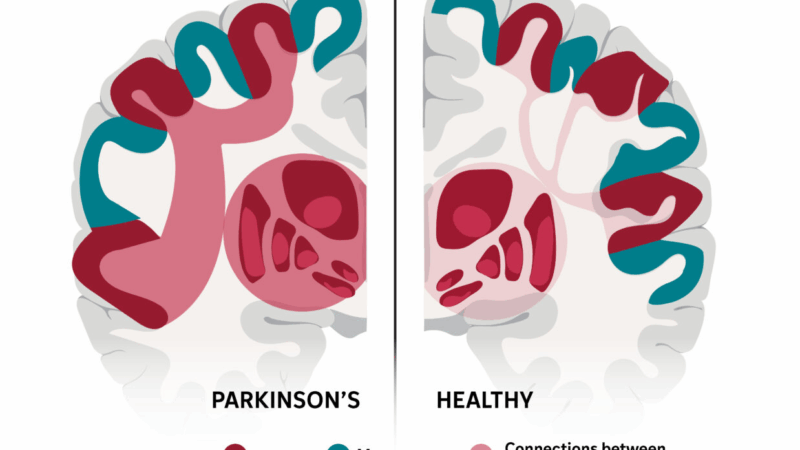

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.