The school shooting industry is worth billions – and it keeps growing

On a sunny day in Grapevine, Texas, three drones are buzzing around the head of a test dummy balanced on a pedestal. It’s part of a demonstration outside the National School Safety Conference.

“We use drones to stop school shootings,” says Justin Marston, the CEO of Campus Guardian Angel, the company selling the drones. In the event of a shooting, remote pilots fly the drones, housed at the school, at the shooter. They shoot pepper balls and run the drones into the shooter to debilitate them.

The technology is one example on a long list of products schools can buy to deter a shooter.

There have been more than 400 school shootings since Columbine in 1999, according to an analysis by The Washington Post. The latest was last month, when a former student opened fire at a Catholic school in Minneapolis. Two students were killed and at least 18 others were wounded.

In the wake of those shootings, an industry has emerged to try to protect schools — and business is booming. According to the market research firm Omdia, the school security industry is now worth as much as $4 billion, and it’s projected to keep growing.

“The school safety and security industry has grown rapidly over the past decade,” says Sonali Rajan, senior director with the research arm of Everytown for Gun Safety, which advocates for gun control. “The challenge right now is that these school safety products, the vast majority, have absolutely no evidence guiding their effectiveness.”

What’s for sale

Inside the school safety conference, vendors in an expo hall showcase panic buttons, bullet-resistant whiteboards, facial recognition technology, training simulators, body armor, guns and tasers.

Tom McDermott, with the metal detector manufacturer CEIA USA, says schools used to be a small fraction of their U.S. business. Now they’re the majority.

“It’s not right. We need to solve this problem. It’s good for business, but we don’t need to be selling to schools,” McDermott says.

Sarah McNeeley, a sales manager with SAM Medical, is selling trauma kits, which include tourniquets, clotting agents and chest seals. She says their customers are traditionally EMTs, fire departments, and military medics, but increasingly, school districts.

“Being prepared and having these devices in the schools is essential,” she says. “Some people want to put their heads in the sand and pretend like it’s not going to happen to them.”

The expo hall is just one part of the conference, organized by the National Association of School Resource Officers, or NASRO. The group also trains school-based police officers on a variety of topics, including how to work with kids who have experienced trauma, and how to intervene before violence occurs.

Sarah Mendoza, a school resource officer in Yoakum, Texas, who attended the conference, says she finds that aspect most meaningful.

“I just sit there and I talk to them and I listen,” she says of working with students. “My connection with the kids is so important because they’re the ones who are going to come and tell me, ‘Hey Mendoza, this is what’s going on. Can you help us?’ or ‘Hey Mendoza, this is how I’m feeling today. What can I do to make myself better?'”

Mo Canady, the executive director of NASRO and a former police officer, says school resource officers are in one of the most challenging policing roles.

“We’re asking a lot of that officer. We’re asking them to be the best tactical person their department could offer,” Canady says. “We’re asking them to be the best informal counselor.”

But when a shooting happens, he says school resource officers need any tools they can get.

What works to prevent school shootings

Gun violence experts say simple things like locked doors can make a difference. Authorities say that likely saved many lives last month in Minneapolis. But a locked door doesn’t necessarily prevent a shooting.

Researchers say investing in school communities that promote a culture of emotional support and trust, as well as robust mental health services, are key to preventing gun violence, as most school shooters are current or former students and are suicidal.

Jillian Peterson, who leads the Violence Prevention Project Research Center at Hamline University, has interviewed people who planned a school shooting, but didn’t carry it out. She said there are often two key reasons they change their minds: The first is that they had trouble accessing a firearm – which is why, she says, safe storage laws are crucial.

The other is that someone helped a young person find hope while they were in crisis.

“We’re spending billions of dollars that could be going to mental health or counselors, all the stuff that we know creates inclusion,” Peterson says.

Still, she says, she understands the allure of an impenetrable school.

“I think it preys on people’s worst fears,” she says. “How do you say no to something if you’re telling me it might save my kid’s life? Of course I want that thing.”

She said trying to buy safety feels very American, just like school shootings.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Many children are just beginning a new school year, but it is one already touched by tragedy. A former student opened fire at a Catholic school in Minneapolis in August. Two children were killed, at least 18 were wounded. That’s the latest in the more than 400 school shootings that have happened since Columbine, according to data from The Washington Post. Since then, a multibillion-dollar industry has emerged around school security. NPR’s Meg Anderson takes us on a trip to see what’s for sale.

MEG ANDERSON, BYLINE: It’s a steamy day in Grapevine, Texas.

(SOUNDBITE OF DRONE BUZZING)

ANDERSON: But that buzzing you hear, it’s not mosquitos. It’s a drone.

JUSTIN MARSTON: We use drones to stop school shootings.

ANDERSON: That’s Justin Marston. He’s the CEO of Campus Guardian Angel, and he’s selling these drones. We’re outside the National School Safety Conference. Three pilots are doing a demonstration.

(SOUNDBITE OF DRONES BUZZING)

ANDERSON: The drones are whizzing around like tiny helicopters, circling a test dummy on a pedestal. He’s the shooter in this demo.

UNIDENTIFIED DRONE OPERATOR: Go in a little high here. Pick up some altitude.

ANDERSON: The drones are meant to disorient. They can even spit out pepper balls. Eventually, they’ll ram into the dummy, knocking it to the ground like a bowling pin. This technology is just one example on a long list of things schools can buy to try to deter a mass shooter. Business is booming.

SONALI RAJAN: The school safety and security industry has grown rapidly over the past decade in particular.

ANDERSON: Sonali Rajan is with the research arm of Everytown for Gun Safety, which advocates for gun control. According to the market research firm Omdia, the school security industry is now worth as much as $4 billion, and it’s projected to keep growing.

RAJAN: The challenge right now is that these school safety products, the vast majority of these have absolutely no evidence guiding their effectiveness.

ANDERSON: Inside the School Safety Conference, there’s an expo hall and a lot more for sale. Down the aisles, people are selling panic buttons, bulletproof whiteboards, facial recognition technology, training simulators, body armor, guns and tasers. Sarah McNeely, with SAM Medical, is selling stop-the-bleed kits.

SARAH MCNEELY: Tourniquet. Trauma shears.

ANDERSON: She says their customers are EMTs, fire departments, military medics, but increasingly, school districts. Tom McDermott is with CEIA USA, a company that makes metal detectors. He says schools used to be a small fraction of their U.S. business. Now, they’re the majority.

TOM MCDERMOTT: Which is nuts. You consider the Secret Service use us. Major League Baseball, NFL, theme parks, they use us. It’s not right. I mean, we need to solve this problem. It’s good for business, but we don’t need to be selling to schools.

ANDERSON: Mo Canady leads the National Association of School Resource Officers, the group that organizes this conference. He says the expo hall is just one part of the gathering. They also train school police officers on how to work with kids who have experienced trauma and how to intervene before violence occurs.

MO CANADY: We’re asking a lot of that officer.

ANDERSON: So, he says, when a shooting happens, they need whatever tools they can get. Gun violence experts say simple things like locked doors can make a difference. Authorities say that likely saved many lives last month in Minneapolis. But that doesn’t necessarily prevent a shooting. Jill Peterson, a criminology professor at Hamline University, says people who plan a shooting but don’t carry it out often change their minds for two reasons. One is that they can’t access a gun. The other is that someone helps them when they’re in crisis.

JILL PETERSON: We’re spending billions of dollars that could be going to mental health or counselors.

ANDERSON: Still, she says, she understands the allure of an impenetrable school.

PETERSON: And I think it preys on people’s worst fears, right? Like, how do you say no to something if you’re telling me it might save my kid’s life? Of course I want that thing.

ANDERSON: She says trying to buy our way to safety feels very American, just like school shootings.

Meg Anderson, NPR News.

Guerilla Toss embrace the ‘weird’ on new album

On You're Weird Now, the band leans into difference with help from producer Stephen Malkmus.

Nancy Guthrie search enters its second week as a purported deadline looms

"This is very valuable to us, and we will pay," Savannah Guthrie said in a new video message, seeking to communicate with people who say they're holding her mother.

Immigration courts fast-track hearings for Somali asylum claims

Their lawyers fear the notices are merely the first step toward the removal without due process of Somali asylum applicants in the country.

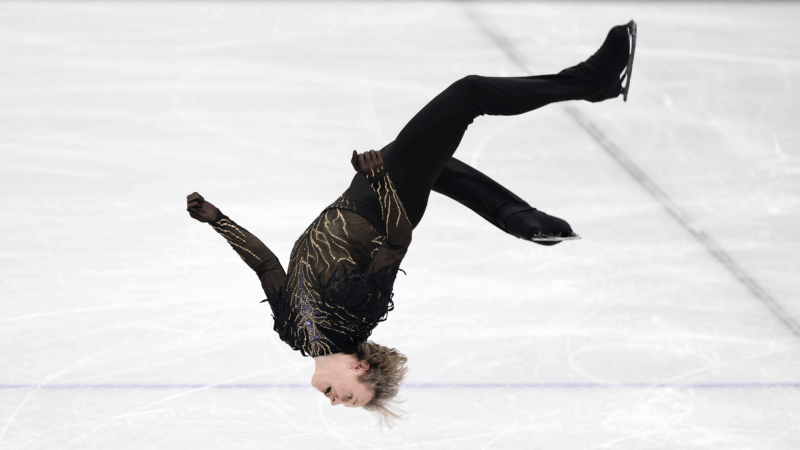

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

U.S. figure skating phenom Ilia Malinin did a backflip in his Olympic debut, and another the next day. The controversial move was banned from competition for decades until 2024.

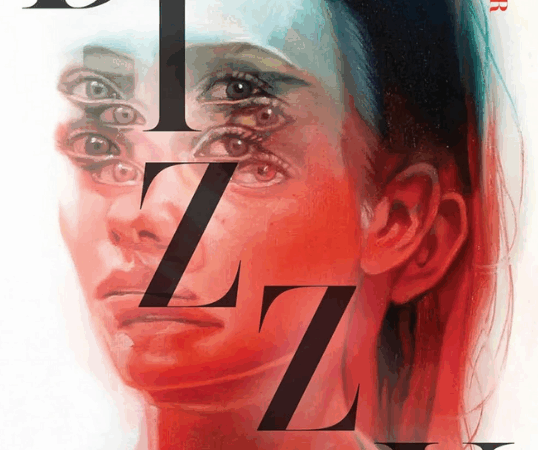

‘Dizzy’ author recounts a decade of being marooned by chronic illness

Rachel Weaver worked for the Forest Service in Alaska where she scaled towering trees to study nature. But in 2006, she woke up and felt like she was being spun in a hurricane. Her memoir is Dizzy.

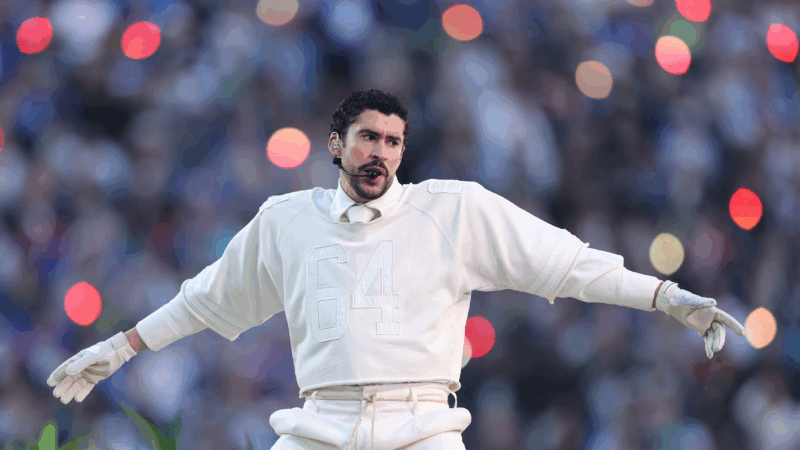

Bad Bunny makes Puerto Rico the home team in a vivid Super Bowl halftime show

The star filled his set with hits and familiar images from home, but also expanded his lens to make an argument about the place of Puerto Rico within a larger American context.