The quest to create gene-edited babies gets a reboot

A Chinese scientist horrified the world in 2018 when he revealed he had secretly engineered the birth of the world’s first gene-edited babies.

His work was reviled as reckless and unethical because, among other reasons, gene-editing was so new and the technology’s full risks were unknown.

China imprisoned the scientist, He Jiankui, for three years for violating medical regulations.

Fast forward to today: Mainstream scientific organizations are encouraging very careful basic research to explore gene-editing and human reproduction. But they still warn any attempts to create more genetically modified children anytime soon should remain strictly off limits.

Now, however, Silicon Valley venture capitalists, futurists, East Coast entrepreneurs, and pronatalists — who fear falling birth rates pose an existential threat to the human race — are eager to push the technology forward. And that’s kindling both great hopes and intense fears.

Fresh interest from private companies

“You’ve got a convergence of people who are thinking that they can improve their children — whether it’s their children’s health, or their children’s appearance, or their children’s intelligence, along with people who are comfortable using the newest technologies and people who have the money and the chutzpah — the daring — to try and do this,” said R. Alta Charo, a University of Wisconsin professor emerita, lawyer and bioethicist, who’s now consulting with government agencies and private companies.

U.S. regulations prohibit editing genes in embryos that could become babies. But that could change, given the Trump administration’s deregulatory stance and support for reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization, some observers say.

And the first company to publicly announce plans to try to genetically modify human embryos to create gene-edited babies just unveiled its plans.

“We want to be the company that does this in the light, with transparency and with good intentions,” Cathy Tie, a biotech entrepreneur, told NPR in an interview about her new company, dubbed: Manhattan Project.

“I think the timing is right for having this conversation,” Tie said. “There’s a lot of promise in this technology.”

As for the company’s name, Tie told NPR, “We chose our name deliberately. We believe the scale of our mission, to end genetic disease, is just as significant as the original science behind Manhattan Project.” Tie said she plans to move slowly and carefully, with stringent bioethical oversight, to explore a variety of gene-editing technologies.

A small scientific team has already been assembled to conduct methodical experiments in a Manhattan lab. The team plans to start by studying mice before moving to primates and then human cells before ultimately working with human embryos.

The company hopes to produce enough evidence to persuade federal officials to fund the research and regulators to approve moving ahead, she said.

“Right now the goal is really just to inform regulators and the public what this technology is capable of — and what it’s not — and hopefully empower regulators in the future, when proven safe and efficient, to allow research in this space,” Tie said. “We hope to support that regulatory approval process.”

Safety is “first and foremost,” she said.

Her ultimate goal, she said, is to prevent serious genetic diseases.

“There are so many diseases that have no cures and there’s not going to be a cure for them for many more decades,” Tie said. “And I think that we have the responsibility to talk about this with patients that do have these terrible diseases and see if they want the option to not pass that on to future generations. Parents should have the choice.”

But the company would not go beyond preventing illnesses, such as the genetic lung disease cystic fibrosis and the inherited blood disorder beta thalassemia, she said.

“Our focus is on disease prevention,” she said. “We draw the line at disease prevention.”

She co-founded the firm with Eriona Hysolli, who headed biological sciences at Colossal Biosciences, which is working on a controversial project to use gene-editing to bring back extinct animals like the wooly mammoth.

“I’m absolutely very excited about this project,” Hysolli, who worked in George Church‘s Harvard genetics lab before Colossal, told NPR in an interview. “I truly believe that these tools are very powerful and can lead to benefits to human health.”

The Manhattan Project did not reveal more details, including how much money had been raised, the investors or a timeline.

Investors see an opportunity

But the company is hardly alone.

“We are definitely evaluating whether it makes sense to actually incubate and help build a company that we think could do this safely and responsibly,” said Lucas Harrington, who co-founded SciFounders, a San Francisco venture capital firm. “I think there’s huge benefit if it can be done safely and responsibly.”

Harrington envisions using newer and hopefully safer gene-editing techniques, such as “base editing,” to modify embryos to make babies. He said his focus too would be on preventing diseases.

The Chinese scientist used the gene-editing technique known as CRISPR, which allows scientists to make very precise changes in DNA much more easily than ever before but can cause potentially dangerous random mutations.

“I think how we’ve been going about it until now has really been burying our head in the sand and not wanting to talk about it because it’s too controversial,” Harrington said. “The tools over the past decade have dramatically changed.”

Others, however, talk about using cutting-edge genetic research to go further than eliminating illnesses before they start.

“The good that Bootstrap Bio can do is to basically speed up the development of this technology and also expand people’s conception of what biotech is actually good for,” said Chase Denecke, the CEO of the California startup Bootstrap Bio, Inc., on the podcast OpenSocietyWTF. Denecke, whose company is reportedly also looking to edit human embryos, declined NPR’s requests for an interview. “I don’t think it’s enough to just say, ‘We’re just going to make you not sick.’ We want to make peoples’ lives actually better,” he said on the podcast.

At least some investors in cutting-edge reproductive technologies agree.

“People can say, ‘Well, you’re playing God by using this type of technology.’ And I say, ‘People would say that with any technology of the past,’ ” said Malcolm Collins, a self-described pronatalist. Collins and his wife, Simone, said they’re supporting a variety of experimental reproductive technologies, ranging from “artificial” wombs and laboratory-made embryos to gene-edited babies.

Some futurists call these “Gattaca Stack” technologies, referring to the 1997 film about genetically engineered people, that could transform human reproduction. Pronatalists hope these developments will help counter declining births.

“I’m really excited for a future within human history where there are some people that have decided to really lean into technologies like this,” Malcolm Collins told NPR in an interview.

His wife agrees.

“We fundamentally believe in reproductive choice and we also very much support parents’ rights to give their children every privilege they can,” Simone Collins told NPR. “And for some people, that means, obviously, eliminating risks of very dangerous diseases. But for other people that means investing in education and tutoring to make them smarter or athletically better. And if people would like to start to do that at a genetic level they should have every right to do so.”

Room for painstaking science

Many scientists favor carefully exploring the editing of DNA in human sperm, eggs and embryos to learn more about human reproduction and possibly someday prevent diseases. And some U.S. scientists working in this field are glad to see private players helping what they consider underfunded research.

The National Institutes of Health “doesn’t typically support embryo research. So if the technology bros are interested, that would be welcome in the field,” said Dr. Paula Amato, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She has been working on embryo editing with her colleague Shoukhrat Mitalipov.

Amato and others stress, however, that whoever is working on this has to first make sure it can be done safely and should focus, at least initially, on preventing disease.

“What I think is positive is: The discussion that will be stimulated through this activity. There is clearly a need for that,” said Dietrich Egli, a Columbia University professor of developmental cell biology. He has raised questions about the safety of CRISPR embryo editing through his experiments.

Egli said he’s talked about this with Brian Armstrong, a billionaire cryptocurrency entrepreneur who recently announced interest in starting an embryo-editing company. Armstrong initially agreed to an interview with NPR through a spokeswoman but then indefinitely postponed.

The moment could be ripe for another look at gene-editing embryos that could be taken to term.

“There’s a president who has some advisers and some political forces whispering in his ear that have a decidedly pronatalist bent that are interested in these technologies,” said L. Glenn Cohen, director of the Harvard Law School’s Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology and Bioethics. “All of that is opening up a moment where some of what would have been unthinkable may now become possible.”

There’s also talk about trying this technology in places like Prospera, a city on an island off the coast of Honduras. Prospera has looser regulations for business involved in fields ranging from cryptocurrency to biotechnology.

Bioethicists warn the risks are concerning

The emphasis on charging ahead worries many observers.

“Move fast and break things has not worked very well for Silicon Valley in health care,” said Hank Greely, a Stanford University bioethicist. “When you talk about reproduction, the things you are breaking are babies. So I think that makes it even more dangerous and even more sinister.”

This new push comes as He Jiankui, the CRISPR babies scientist, has shifted from repentant to defiant since being released from prison.

“AI is threatening humanity, we must fight back by gene editing,” he recently wrote on X.

Tie was briefly married to He, but Tie told NPR they recently divorced. He will have nothing to do with her new company, she said.

“The nature of my relationship with him was personal, not professional and I’m also no longer married to him. He is not involved,” Tie said. “I wish him all the best.”

Nevertheless, all the renewed interest has contributed to anxiety among opponents of gene-edited babies.

“I do think this is a dangerous moment,” said Ben Hurlbut, a bioethicist at Arizona State University who recently helped organize an international meeting on inheritable human gene-editing.

“Just because you can do it doesn’t mean you should do it,” he said. “Do we need to tell us ourselves again that we shouldn’t go there?”

Others agree.

“Human heritable gene editing is clearly a terrible solution in search of a problem,” said Tim Hunt, chief executive officer at the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which along with the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy and the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy recently called for a 10-year moratorium on inheritable gene-editing. “If you make a mistake, the mistake passes onto all future generations. So that’s a pretty big ethical roll of the dice.”

Many critics argue that this movement is today’s version of eugenics, the long-discredited pursuit of supposedly genetically superior people.

“I think we should be deeply worried about this,” said Francoise Baylis, a bioethicist and professor emerita at Dalhousie University in Canada. “This is a continuation of the eugenic project that has been sort of in vogue at different times throughout civilization. This is just the modern incarnation of that idea.”

Others fear turning human reproduction into just another consumer product.

“We’re going to mass-produce genetically engineered human beings. And I think that’s a very dangerous way to approach these technologies,” said Katie Hasson, the associate director of the Center for Genetics and Society, a genetics technology watchdog group in Berkeley, Calif. “I’m very worried that all of this together means we’re headed straight into a new era of high-tech, market-based eugenics.”

But the Manhattan Project’s Hysolli argues it would be unethical not to use the technology if it’s safe.

“If we have the tools to prevent a disease that will be passed down for generations, is it more ethical to do it or not do it?” Hysolli said. “I would argue it would be more ethical to stop the mutation.”

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Genetically engineered humans may still sound like the stuff of science fiction, but the quest to create genetically modified babies is getting a reboot. NPR’s health correspondent Rob Stein brings us the story.

ROB STEIN, BYLINE: About a year before the pandemic hit, a scientist in China, He Jiankui, revealed that he had secretly engineered the birth of the first CRISPR gene-edited babies.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

HE JIANKUI: Two beautiful little Chinese girl named Lulu and Nana came crying into the world as healthy as any other babies a few weeks ago.

STEIN: The birth of the twins was reviled as reckless and unethical because, among other things, CRISPR gene editing was so new. China imprisoned him for three years for violating medical regulations. Fast forward to today. Most scientists and bioethicists still say that gene editing of human embryos to produce children would be irresponsible. But Silicon Valley startups, East Coast entrepreneurs and some so-called pronatalists, who fear declining birth rates pose an existential threat, are eager to try. Alta Charo is a lawyer and bioethicist from the University of Wisconsin.

ALTA CHARO: You’ve got a convergence of people who are thinking that they can improve their children, whether it’s their children’s health or their children’s appearance or their children’s intelligence, along with people who are comfortable using the newest technologies and people who have the money and the chutzpah, the daring, to try and do this through starting companies that would bring these forces together.

STEIN: In fact, the first private company just announced plans to pursue editing human embryos. Entrepreneur Cathy Tie co-founded the startup in New York City. It’s called Manhattan Project.

CATHY TIE: Manhattan Project will explore how to do gene correction in human embryos more safely. But we want to be the company that does this in the light, with transparency and with good intentions.

STEIN: Tie’s Manhattan Project plans to test newer, potentially less risky gene-editing techniques to hopefully prove it would be safe to modify embryos to make healthier babies. Tie says she’d only try to prevent disease.

TIE: I think there are so many diseases that have no cures and there’s not going to be a cure for them for many more decades. And I think that we have the responsibility to talk about this with patients that do have those heritable diseases and see if they want the option to not pass that on to their future generations.

STEIN: But some investors are looking to go further. Malcolm Collins and his wife Simone are vocal pronatalists who say they’re funding many cutting-edge reproductive technologies.

MALCOLM COLLINS: People can say, well, you’re playing God by using this type of technology. And I’d say people would say that with any technology of the past. They’d say you’re playing God with glasses. They’d say you’re playing God with blood transfusions. I’m really excited for a future within human history where there are some people that have decided to really lean into technologies like this.

STEIN: To prevent diseases but also someday maybe to design children with traits their parents want. Here’s Simone Collins.

SIMONE COLLINS: We fundamentally believe in reproductive choice, and we also very much support parents’ rights to give their children every privilege they can. And for some people, that means obviously eliminating risks of very dangerous diseases. But for other people, that means investing in education and tutoring to make them smarter or athletically better. And if people would like to start to do that at a genetic level, they should have every right to do so.

STEIN: Now, many scientists endorse researching genetic modification of sperm, eggs and embryos but carefully and with limits. Dr. Paula Amato works on embryo editing at the Oregon Health and Science University.

PAULA AMATO: NIH doesn’t typically support human embryo research, so if the technology bros are interested, that would be welcome in the field.

STEIN: As long as they make safety the top priority, she says, and at least initially would only try to edit out diseases. U.S. regulations prohibit trying to make gene-edited babies, but some wonder whether that could change. Glenn Cohen is a lawyer and bioethicist at Harvard.

GLENN COHEN: There’s a president who has some advisers and some political forces whispering in his ear that have a decidedly pronatalist bent that are interested in these technologies. All of that is opening up a moment where some of what would have been unthinkable may now become possible.

STEIN: For many, all this sets off alarm bells. Hank Greely is a bioethicist at Stanford.

HANK GREELY: Move fast and break things has not worked very well for Silicon Valley in health care because when you talk about reproduction, the things you are breaking are babies. And I think that makes it even more dangerous and even more sinister.

STEIN: And remember the CRISPR baby scientist? Since getting out of a Chinese prison, he’s gone from repentant to defiant and is vowing to resume working on gene-edited babies, too. Tie, the Manhattan Project co-founder, was briefly married to He, but says they recently divorced and that he has nothing to do with her new human embryo gene-editing company.

Rob Stein, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF LOLA YOUNG SONG, “CONCEITED”)

Lindsey Vonn says she suffered ‘complex tibia fracture’ in her Olympic downhill crash

The 41-year-old star said her torn ACL was not a factor in her crash. "While yesterday did not end the way I had hoped, and despite the intense physical pain it caused, I have no regrets," she wrote.

Guerilla Toss embrace the ‘weird’ on new album

On You're Weird Now, the band leans into difference with help from producer Stephen Malkmus.

Nancy Guthrie search enters its second week as a purported deadline looms

"This is very valuable to us, and we will pay," Savannah Guthrie said in a new video message, seeking to communicate with people who say they're holding her mother.

Immigration courts fast-track hearings for Somali asylum claims

Their lawyers fear the notices are merely the first step toward the removal without due process of Somali asylum applicants in the country.

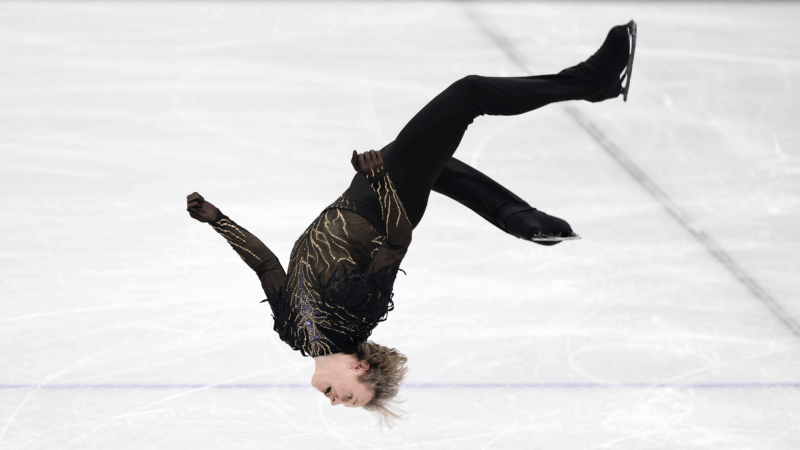

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

U.S. figure skating phenom Ilia Malinin did a backflip in his Olympic debut, and another the next day. The controversial move was banned from competition for decades until 2024.

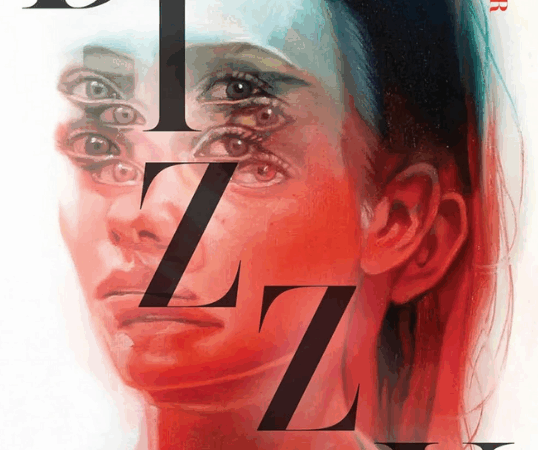

‘Dizzy’ author recounts a decade of being marooned by chronic illness

Rachel Weaver worked for the Forest Service in Alaska where she scaled towering trees to study nature. But in 2006, she woke up and felt like she was being spun in a hurricane. Her memoir is Dizzy.