The long recovery on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, ‘ground zero’ for Hurricane Katrina

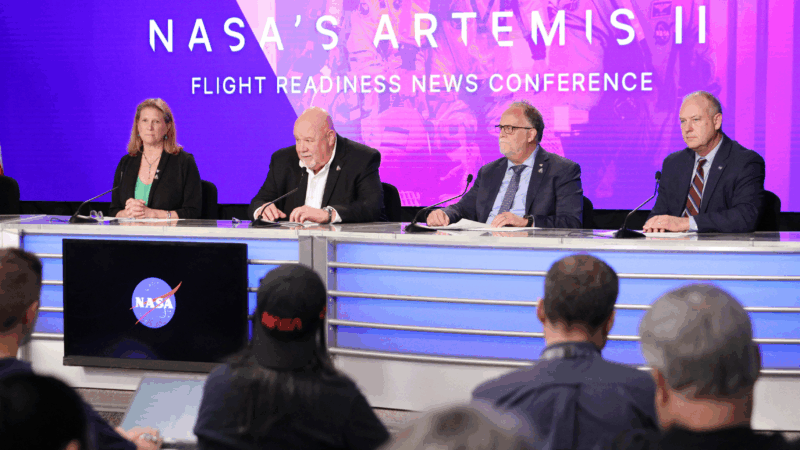

Former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour stands before a wall-sized satellite image of Hurricane Katrina as it headed for landfall on Aug. 29, 2005.

“The eye came in right there over the Pearl River, which is the boundary between Louisiana and Mississippi,” he says.

It was packing winds of 120 miles an hour and a storm surge nearing 30 feet. “The most powerful winds, and storm surge are in the upper right-hand corner. And that hit us,” Barbour recalls.

Barbour is walking through a new exhibit at the state-funded Two Mississippi Museums in Jackson. It’s called Hurricane Katrina: Mississippi Remembers and features photographs of the aftermath by Melody Golding.

While much of the focus marking 20 years since Hurricane Katrina is on New Orleans, where federal levees failed and flooded the city, the historic storm also decimated the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

The state’s entire 70-mile shoreline was inundated with Katrina’s three-story-high storm surge. It knocked out bridges, buckled roads, and washed away homes and businesses. The storm killed 238 people in Mississippi and nearly 1,400 overall.

“It looked like the hand of God had wiped away the coast,” Barbour recalls. “Utter obliteration.”

He says some 60,000 structures were uninhabitable, and more than 25,000 were flat out gone. “We created a new verb,” he says. “I’ve been slabbed.” As in, there’s nothing left of my house but the concrete slab it was built on. Coastal flooding reached 10 miles inland, and hurricane-force winds stretched well into north Mississippi.

Barbour was in his first term as governor of Mississippi, back home after years as a Republican power broker in Washington, D.C., including serving as political director in the Reagan White House, and chairman of the Republican National Committee.

The first crisis after Katrina hit came immediately when he realized that federal aid was not on the way. The Federal Emergency Management Agency was overwhelmed and couldn’t rush food and water to the Gulf Coast. “From almost the beginning, the logistical plan collapsed,” Barbour says. “And we weren’t getting what we’re supposed to be getting.”

The state turned to the military — the United States Northern Command — for help. The unit flew Army rations to Biloxi. After the initial bumps, though, Barbour says the federal response improved and the state got help, including reimbursement for cleaning up debris, an endeavor that took a year and a half. Barbour says Mississippi needed FEMA to begin the road to recovery.

“It would have been very, very hard to do without FEMA,” he says, skeptical of the Trump administration’s talk of eliminating the agency. “Could you organize it in a different way? Maybe. But to have no federal disaster assistance program would be a catastrophe. Often.”

Barbour says major disasters require lots of outside help. For instance, 48 other states came to the rescue in Mississippi, sending National Guard units, law enforcement officers, and road and power crews. Some left their vehicles behind as replacements for the local police whose fleets were flooded out.

But more than $5 billion in federal grants were key, Barbour says. It didn’t hurt that Mississippi Republican Thad Cochran was the powerful chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee at the time. Barbour says he also found allies across the political aisle — Massachusetts Democrat Barney Frank offered to corral votes in the House for Mississippi relief.

Barbour’s approach to Mississippi’s recovery was to focus on bringing back jobs, schools, and most important, housing to get people to return to the coast.

The rebuilding effort got a huge boost from the more than 900,000 volunteers who came to help rebuild Mississippi in the five years after Katrina.

“Really the most incredible saving grace,” says Derrick Christopher Evans of Gulfport. Volunteers helped rebuild the historic Turkey Creek community where he’s from. He says they gave people a sense of hope, along with the material recovery.

“If the non-profits and the volunteers didn’t do it, there was nothing coming in if you didn’t have the means.”

Evans was critical of the state’s early emphasis on getting casinos and the port quickly back in business. He would have liked to have seen more investment in struggling neighborhoods.

Turkey Creek is considered a historic district because it was founded just after the Civil War by former slaves and freed men. It’s now surrounded by heavy industry.

It’s about 7 miles inland, so residents mostly didn’t have flood insurance. So Evans says they had to figure out the post-disaster ecosystem of government and private resources, a daunting endeavor. “It’s not just getting back in your house, man. When you get hit by Katrina……it’s like you got to learn the phone book,” he says. “It was mayhem and I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

Evans says he feels like his community is in a continuous state of recovery.

Mississippi’s recovery over the last 20 years has been uneven, with some places coming back sooner than others. In Waveland, you still see empty slabs dotting neighborhoods, and the downtown business district is mostly empty.

“That sense of main town, Main Street USA is missing,” says Bernie Cullen, chairperson of the aptly named Ground Zero Museum in the city. “Here we were, ground zero.”

She says it took years for the city to feel like home again, describing how the community would grasp onto small signs of progress. Like when power crews were able to get streetlights back up so it wasn’t so dark, or when Walmart reopened.

“There’s always hope,” she says. “Even in the bleakest times, you take one day at a time. You say, ‘I’m going to rebuild.'”

But not everyone came back. In the decade after the storm, Waveland lost nearly 20% of its population, which was 7,800 before Katrina.

The recovery here has been a long slog, according to Waveland Mayor Jay Trapani. “Ninety percent of the city was destroyed in Hurricane Katrina,” he says. “I remember driving in from where I evacuated and hearing on the radio it would take 10 years for the coast to come back. And here we are sitting at 20 and we’re still trying to recover.”

One factor has been stricter building requirements due to the high flood risk here, which makes construction more expensive. For instance, he had to rebuild his beachfront house on concrete pilings 24 feet above sea level.

Waveland needed a new city hall, along with new police and fire stations. It wasn’t until 2016 that the police department moved out of temporary quarters and into its new building. The force had to start from scratch after Katrina flooded the department, which had been located about 3 miles inland.

Police Chief Michael Prendergast was assistant chief in 2005. He recalls at the height of the storm, 27 officers and staff who hunkered down at the headquarters had to bust through storm shutters to escape the flooding building. They survived by clinging to a row of Crepe Myrtles out front, waves lashing around them.

“Everybody hung onto the trees,” he says. “We were hugging each other, trying to keep each other warm and everybody mentally stable.” Prendergast says it took about five hours for the water to go down. Then the reality of what they were up against set in.

“It was kind of like an apocalypse,” says Lisa Parker, the chief’s administrative assistant, the same job she had in 2005.

Nearly everyone on the police force had lost their homes and belongings. And they had no equipment, either. “We’re the ones who are supposed to keep the law and order,” she says. “But we were in the same boat as everybody else. You only had so much things you can do with no means to do it. No guns, no radios, no cars, no anything.”

“Katrina didn’t discriminate,” says Prendergast. “Rich, poor, didn’t matter. You know, how you lived or whatever. Katrina, like, wiped out the whole city.”

Katrina also wiped away cultural treasures in Waveland, including the United Methodist Gulfside Assembly, founded a century ago as a sprawling waterfront retreat for African-Americans.

“It hit Gulfside like a brick wall,” says Executive Director Cheryl Thompson. For her, it was a gut punch to find nothing left. No hotel, or chapel, or auditorium, or anything.

“It felt like a relative or somebody I knew had died. It was just very emotional for me. And even now, it’s like a disbelief. Like how could we have lost all of that?” Thompson grew up in New Orleans and spent her childhood summers at Gulfside Assembly, which she says was an anchor for the Black community in the segregated South.

“There were no other places for us to go where we felt free to stay in the hotel, to play, to swim in the water, to have our own place,” Thompson says. “There weren’t places where we could go to stay in hotels. I’m 77 years old. And so when I was growing up, that was not it was not a thing.” It was a place for weddings, reunions, and civil rights strategy meetings, she says.

Twenty years after Katrina the organization is still struggling to regroup, and working out of a donated church building. “You grieve, but you have to, we have to move on. You know, it’s not going to be what it was before, but we can still do our ministry,” Thompson says.

The spirit of keep moving forward is something you hear time and time again talking to Katrina survivors.

Deep in the swamp where the Pearl River empties into the Gulf of Mexico, Jayne Crapeau walks along the boardwalk behind her restaurant — Turtle Landing Bar and Grill. The resident one-eyed alligator, Pedro, pokes his snout above the glass-smooth bayou to greet her.

Crapeau has had the bar for 23 years here in Pearlington, the last stop in Mississippi before the Louisiana state line.

“We’re still here, thank goodness,” she says. “This little town’s gone through hell.”

Crapeau and her husband rode out Katrina on the second floor of the building. She says the water got chest high and didn’t start going down until the next day. “Scared as hell upstairs. We lost all communication.”

People in Pearlington were on their own for four days before helicopters started dropping food and water.

Crapeau says they organized in the parking lot, handing out warm beer and serving what canned goods she could salvage from the flooded kitchen. Once help arrived, they set up a tent to feed people using generator power.

It was two-and-a-half months before Pearlington got electricity back. And it was six years before Crapeau repaired the bar – new roof, new electrical, new plumbing, and a new kitchen, moved upstairs to higher ground. “It was a struggle but we did it.”

At 69, and now fighting cancer, she still works the kitchen dishing up her signature cheeseburger but has fewer customers than she did 20 years ago.

Pearlington has lost about a third of its population since Katrina. The local elementary school closed. Crapeau says parts of town have never come back from the hurricane. “There’s several homes that have been gutted just sitting there. There’s some that’s just crumbling.”

But she’s not giving up.

“I’m trying to pull Pearlington back,” says Crapeau. “I just hope the hell we never see another one.”

“Katrina revealed character,” says former Gov. Barbour, now 77, reflecting on what he sees as the takeaway from the Katrina experience in Mississippi.

“Our people got knocked down flat, but they got right back up, hitched up their britches and went to work.”

Barbour says his mother always taught him that crisis and catastrophe do not create character but instead reveal it. He sees that now in the perseverance of Mississippi’s Katrina survivors.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Twenty years ago, Hurricane Katrina devastated the northern Gulf Coast, killing nearly 1,400 people and destroying communities from Louisiana to Alabama. Much of the focus in marking the Katrina anniversary is on New Orleans, where federal levees failed and flooded the city. But the hurricane also decimated the Mississippi Gulf Coast, where it made landfall. NPR’s Debbie Elliott revisits the daunting aftermath of the disaster with the state’s governor at the time, Haley Barbour.

DEBBIE ELLIOTT, BYLINE: Former Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour stands before a wall-sized satellite image of Hurricane Katrina as it headed for landfall on August 29, 2005.

HALEY BARBOUR: It came in – the eye came in right there on the Pearl River, which is the boundary between Louisiana and Mississippi.

ELLIOTT: It was packing winds of 120 miles an hour and a storm surge nearing 30 feet.

BARBOUR: The most powerful winds, storm surge, are in the upper-right-hand corner. And that hit us.

ELLIOTT: Barbour is walking through a new exhibit in Jackson, at the state-funded Two Mississippi Museums. It’s called Hurricane Katrina: Mississippi Remembers. The entire 70-mile Mississippi coast was inundated with Katrina’s three-story-high storm surge, knocking out bridges, buckling roads and washing away homes and businesses.

BARBOUR: We had about 60,000 structures that were uninhabitable. More than 25,000 that were gone. We created a new verb. The verb was slabbed (ph). I’ve been slabbed.

ELLIOTT: As in, there’s nothing left of my house but the concrete slab it was built on. Coastal flooding reached 10 miles inland, and hurricane-force winds stretched into north Mississippi. Two hundred and thirty-eight people were killed in the state. Barbour says it was like nothing he’d seen before.

BARBOUR: When I flew over the coast in a helicopter after the hurricane, it looked like the hand of God had wiped away the coast. Utter obliteration.

ELLIOTT: Barbour was in his first term as governor of Mississippi, returning home after years as a Republican power broker in Washington, D.C., including serving in the Reagan White House. The first crisis after Katrina hit came immediately, Barbour says, when he realized that federal aid was not on the way. FEMA was overwhelmed, and couldn’t rush food and water to the Gulf Coast.

BARBOUR: From almost the beginning, the logistical plan collapsed, and we weren’t getting what we were supposed to be getting.

ELLIOTT: After the initial bumps, though, he says the federal response improved and the state got what it needed, including reimbursement for getting power and water systems back up and clearing debris – an endeavor that took a year and a half. The state got more than $5 billion in federal grants to help rebuild, and 48 other states offered resources.

Barbour’s focus was on bringing back jobs, schools and – most importantly – housing to get people to return to the coast. The rebuilding effort got a huge boost from the more than 900,000 volunteers who worked in Mississippi in the five years after Katrina.

DERRICK CHRISTOPHER EVANS: Really, the most incredible saving grace.

ELLIOTT: That’s Derrick Christopher Evans of Gulfport. He says volunteers helped to rebuild the historic Turkey Creek community where he’s from.

EVANS: The one thing that’s just given people hope, as well as material recovery.

ELLIOTT: Evans was critical of the state’s early emphasis on getting casinos and the port quickly back in business. He would have liked to have seen more investment in struggling neighborhoods. Turkey Creek was founded just after the Civil War by former slaves and freedmen. It’s now surrounded by heavy industry. Because it’s about seven miles inland, residents mostly did not have flood insurance, so navigating the aftermath of Katrina was daunting.

EVANS: It’s not just getting back in your house, man. When you get hit by Katrina, the entire book of the federal apparatus of the state – its like you got to learn the phone book. So it was mayhem, man. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.

ELLIOTT: Even though it’s been 20 years, the scars are fresh, deep in the swamp where the Pearl River empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

JANYNE CRAPEAU: Pedro. Come here, Pedro. There he comes.

(SOUNDBITE OF TAPPING)

CRAPEAU: I see you.

ELLIOTT: Janyne Crapeau walks along the boardwalk behind her restaurant, Turtle Landing Bar & Grill. The resident one-eyed alligator, Pedro, pokes his snout above the glass-smooth bayou to greet her. She’s had this bar for 23 years here in Pearlington – the last stop in Mississippi before the Louisiana state line.

CRAPEAU: It’s a beautiful little town. A lot of good people. They’ll help you in any kind of way they can. But if you step on one of us, God bless you (laughter), you know?

ELLIOTT: It’s where Katrina made landfall.

CRAPEAU: This little town’s gone through hell.

ELLIOTT: Crapeau and her husband rode out Katrina on the second floor of the building, where the water got chest-high and didn’t start receding until the next day. It was harrowing.

CRAPEAU: Scared as hell, upstairs. We lost all communication.

ELLIOTT: People in Pearlington were on their own for four days, she says, before helicopters started dropping food and water. Crapeau says they set up in the parking lot, handing out warm beer and serving what canned goods she could salvage from the flooded kitchen. Once help arrived, they set up a tent to feed people using generator power. It was 2 1/2 months before Pearlington got electricity back, and it was six years before Crapeau repaired the bar – new roof, new electrical, new plumbing and a new kitchen put upstairs.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS STOMPING)

ELLIOTT: At 69 and now fighting cancer, she still works in the kitchen, dishing up her signature cheeseburger.

CRAPEAU: Half-pound of ground chuck.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLAPPING)

CRAPEAU: It was a struggle, but we did it.

ELLIOTT: Pearlington has lost about a third of its population since Katrina. Crapeau says you can still see the hurricane’s footprint – empty slabs and crumbling structures. But she’s not giving up.

CRAPEAU: I’m trying to pull Pearlington back, but you have to have people to help you. I don’t know. I just hope to hell we never see another one.

BARBOUR: Katrina revealed character.

ELLIOTT: Haley Barbour, now 77, reflects on what he sees as the takeaway from the Katrina experience in Mississippi.

BARBOUR: Our people got knocked down flat, but they got right back up, hitched up their britches and went to work.

ELLIOTT: Barbour says his mother always taught him that crisis and catastrophe do not create character, but instead reveal it. He sees that now in the perseverance of Mississippi’s Katrina survivors.

Debbie Elliott, NPR News, Pearlington, Mississippi.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUDDY WATERS SONG, “THE SAME THING”)

China slams Trump’s trade investigation, as it approves a 5-year economic plan

China's Foreign Ministry criticized the Trump administration's trade investigation as a "pretext" for tariffs. Meanwhile, China is moving ahead with a five-year plan that may rankle trade partners.

NASA targets Artemis II crewed moon mission for April 1 launch

A six-day launch window opens on April 1 from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The lunar orbital mission would be the first time humans have returned to the moon since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Auburn football player uses NIL funds to open a community hub in Birmingham

Jourdin Crawford, a freshman defensive lineman at Auburn, used earnings from a Name, Image, and Likeness deal to give back to his hometown.

Fear of Iranian mines in the Strait of Hormuz could further slow the flow of oil

Attacks by Iran have already nearly halted the flow of oil through the vital waterway as commercial ship crews fear being hit by missiles, drones or mines.

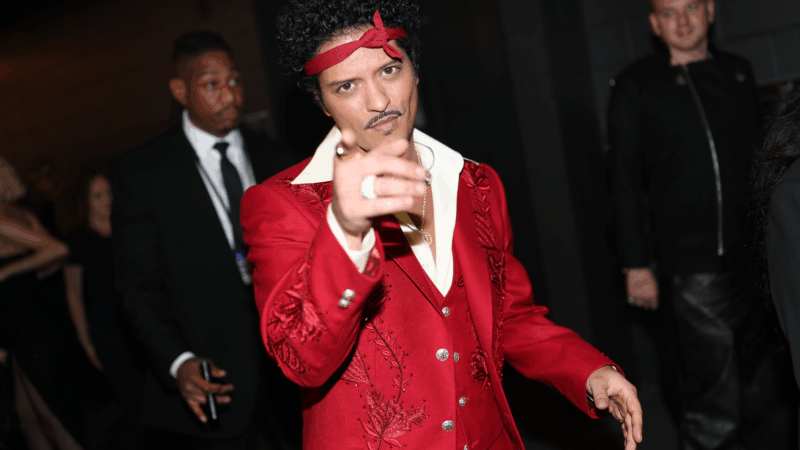

Bruno Mars adds yet another milestone to his career with ‘The Romantic’

Bruno Mars is the most-listened to artist in the world on Spotify. He's won 16 Grammys. In case you thought there were no battles left for him to win, this week he unlocked another achievement.

There’s more than one path to a confessional song

On new albums by viral sensation Yebba and studio whiz Pimmie, it's clear modern R&B has been clearing space for vastly different stripes of singer-songwriter.