Ten years after Freddie Gray’s death, his neighborhood looks for hope

Standing outside of a once-bustling recreation center in a West Baltimore neighborhood, Tracey Malone reflected on the community that she grew up in. “Sandtown-Winchester community is a loving community. It is a community where neighbors care for each other, you know each other,” Malone, who is now the executive director of the Sandtown-Winchester Community Collective said.

Though brightly colored murals wrap around the retaining walls of the recreation center, the doors are closed. The city closed the recreation center in 2021, leaving the neighborhood’s young people with few places to go. “I grew up here. I grew up in Lillian Jones Rec Center,” Malone said. “My mom still owns a home here, and my brother was murdered in the same community. And I am here giving back to this community, because he was a kid that gave back.”

Sandtown was once a thriving locus of Black cultural life in Baltimore, but over the years, fell into disrepair and decline. For some who are invested in the neighborhood, as Malone is, the still-shuttered recreation center has become a visible symbol of persistent challenges. And the rec center’s future is a sign of what the future of Sandtown could look like.

“Where’s the hope? Ten years later, we’re still standing here,” said Malone. “And where’s the hope? Where’s the change?”

Ten years ago this month, the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray put the neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester in the national spotlight. But Sandtown’s struggle long predates Gray’s arrest and death.

Gray was arrested in April 2015 in the Gilmor Homes public housing complex in Sandtown, and placed in the back of a police van. While he was being transported by Baltimore police officers, he suffered a severe neck injury. Gray died in a hospital a week later.

Following his funeral, unrest broke out with protests across majority-Black West Baltimore that later spilled into other parts of the city. Some involved violence and destruction, including the burning of a CVS store in Sandtown – in images seen around the country.

“Freddie Gray was just the lighting of the fuse that blew up the cage,” said Pastor Duane Simmons. He leads Simmons Memorial Baptist Church in Sandtown.

Outside Simmons Memorial, people line up to receive food aid, handed out from a van parked alongside the building. Inside, the church is no-frills. There are visible holes in the floors and walls inside the church’s central office.

“We deal with over a thousand people who have an addiction problem. We feed about 4 to 600 people a week. With no money. Because here at Simmons Memorial, we believe that need should be the driving force of your ministry, not surplus” the pastor said.

Simmons has been leading this church for decades, since 1990. And in 2015, when Freddie Gray’s death sparked the uprising in Sandtown and across the city of Baltimore, he says the church provided resources, and safe haven. “Three and a half weeks. We never closed. 24 hours. It was the safest spot in which to be because not a glass was broken on this church,” he said. “We were present. Helping, lifting, encouraging.”

After Gray’s death and the unrest that followed, political leaders visited Sandtown and made promises of investment and sweeping change. Then-mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake promised $4.2 million dollars for programming for young people. There was a program launched by the mayor and Maryland’s governor at the time, Larry Hogan, to demolish vacant buildings and rebuild blighted blocks.

But Simmons, and others, say many promises never materialized — and that after ten years there’s waning attention. “The politicians that represent this community are never here. They rub shoulders with the aristocrats, but barely speak to the proletariat.”

Some change did come to Sandtown and to Baltimore. The Department of Justice investigated the city’s police department — finding that it disproportionately targeted Black people for stops and arrests, among other things. The city entered a consent decree in 2017 to address those issues. That same year, the city, in partnership with private donors, introduced a renovated Western District police station to serve the community.

There have been setbacks in Sandtown, too. “We had a young lady who was murdered in front of this rec center,” Baltimore City Councilman James Torrence said in an interview outside the still-shuttered rec center. “The young people were unable to return because once we shut down the rec to figure out how we can do trauma-informed response to having them come back, someone stole the pipes and wiring.”

Torrence said that there’s still a lot of need in Sandtown, and that part of his job is showing members of this community that their government can meet their needs.

And the input from Sandtown, Torrence said, is the reason that, for now, plans are on track to bring the rec center back. “People think they’re left behind. So the apathy for people is high, but it’s also getting the trust so that they come back out and trust us,” he said. “The fact that they were a little scared when we told them, tell us what you want for your rec center. They’re like, What’s the budget? Dream is what the budget is, and then we’ll figure it out.”

He said the city hopes to start building a $26 million new facility by 2027. “There’s been a consistent voice among the black women leading this movement in this neighborhood that we want this thing and this is how we want it. And when I say they leave no room without a commitment. Every time I met with them, a commitment was made and it had to be followed through. And I think that the next thing is about the follow through.”

Activist Tracey Malone hopes that a new rec center can create the same connections for a new generation of young people in Sandtown that she found decades ago.

“This community still needs to heal. And how do we heal besides coming together,” she asked. “We are creating hope here in Sandtown. Regardless of all the money that came, that did not stay here in Sandtown, Sandtown still thrives.”

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Reporting from a quiet block of a West Baltimore neighborhood – it’s spring break. Children are out of school, but the basketball courts and a nearby park are all empty. Brightly colored murals climb along the concrete retaining walls that surround a neighborhood rec center, but the doors are locked. It has been closed for roughly four years.

TRACEY MALONE: Sandtown-Winchester community is a loving community. It is a community where neighbors care for each other. You know each other.

SUMMERS: That’s Tracey Malone. For her, this rec center is more than just a building. Sitting at the center of the small neighborhood, the rec center is where she made lifelong friendships.

MALONE: I grew up here. I grew up in Lillian Jones Rec Center. My mom still owns a home here, and my brother was murdered in this same community, and I am here giving back to this community because he was a kid that gave back.

SUMMERS: Even though Malone has moved out of this neighborhood, she’s the executive director of the Sandtown-Winchester Community Collective. She’s organized behind the cause of reopening the rec center and, in turn, making this neighborhood a place where kids can thrive, can see a future. As we talk, she gestures around.

MALONE: It was just deserted. The weeds were growing extremely high. There was a lot of – there was way more trash than it is now. That playground is still messed up. It’s like a sinkhole playground.

SUMMERS: And for some who are invested in this neighborhood or have roots here, like Malone, this rec center has become a symbol of what Sandtown could be.

MALONE: Where’s the hope? Ten years later, we’re still standing here asking, where’s the hope? Where’s the change?

SUMMERS: Ten years ago this month, the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray put this neighborhood in the national spotlight. He was arrested in a public housing complex in Sandtown called Gilmor Homes and placed in the back of a police van. As Gray was being transported, he suffered a severe neck injury. Gray died in a hospital about a week later.

UNDENTIFIED PASTOR: The Lord giveth…

UNIDENTIFIED CONGREGATION: The Lord giveth…

UNDENTIFIED PASTOR: …And the Lord taketh away.

UNIDENTIFIED CONGREGATION: …And the Lord taketh away.

UNDENTIFIED PASTOR: …And the Lord taketh away.

SUMMERS: The medical examiner for the state ruled Gray’s death a homicide. The officers involved in his death were ultimately acquitted. Gray’s treatment at the hands of police sparked protests across Baltimore.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: You’re going to see tear gas. You’re going to see pepper balls. We’re going to use appropriate methods to ensure that we’re able to preserve the safety of that community.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: Police came and blocked off everything. If you – anyone that’s blocked off’s going – you feel me? – they going to want a way to get out, so people start moving, police start getting more aggressive. Before anything happened, they started firing smokescreens and all that and made everything violent.

DUANE SIMMONS: Freddie Gray was just the lighting of the fuse that blew up the cage.

SUMMERS: That’s Pastor Duane Simmons. I meet him at his church in Sandtown. When we sit down in the church central office, there’s a room full of people next door.

SIMMONS: We deal with over a 1,000 people who have an addiction problem. We feed about 4- to 600 people a week with no money because here at Simmons Memorial, we believe that need should be the driving force of your ministry, not surplus.

SUMMERS: Simmons has been leading this church for decades, since 1990, and in 2015, when Freddie Gray’s death sparked an uprising in Sandtown and across the city of Baltimore, he says the church provided resources and safe haven.

SIMMONS: Three-and-a-half weeks, we never closed, twenty-four hours. It was the safest spot in which to be because not a glass was broken on this church. We were present, helping, lifting, encouraging.

SUMMERS: After Gray’s death and the unrest that followed, politicians made a number of promises to Baltimore. Then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake promised $4.2 million for programming for young people. There was a program launched by the mayor and Maryland’s governor at the time, Larry Hogan, to demolish vacant buildings and rebuild blighted blocks. There were also promises to pour more resources into Sandtown. Tracey Malone remembers pledges to address vacant housing, construct a community youth center, to create more accessible green spaces, among others. But Simmons and others say many of those promises never materialized and that after 10 years, there’s waning attention.

SIMMONS: The politicians that represent this community are never here. They rub shoulders with the aristocrats but barely speak to the proletariat.

SUMMERS: Some change did come to Sandtown and to Baltimore. The Department of Justice investigated the city’s police department, finding that it disproportionately targeted Black people for stops and arrests, among other things. And the city entered a consent decree in 2017 to address those issues.

MALONE: Oh, yeah, you did get an upgraded police station in the last 10 years.

SUMMERS: That’s Tracey Malone again. The skepticism on her face is clear.

Several years ago, the city, in partnership with private donors, overhauled the Western District Police Station that serves Sandtown. But there have been setbacks here, too.

JAMES TORRENCE: We had a young lady who was murdered in front of this rec center. The young people were unable to return because once we shut down the rec to figure out how we can do trauma-informed response to having them come back, someone stole the pipes and the wiring.

SUMMERS: This is James Torrence, the Baltimore city councilman who represents this neighborhood. He says there is still a lot of need in Sandtown, and community members are stepping up to make sure needs are met.

TORRENCE: People are actively loving on each other. This is – this community is close-knit. They were creating pop-ups on this field right here. They painted this mural here along the rec center. It was a collective energy. There’s a youth league that’s here every Saturday in the summertime that does football and lacrosse, and it’s a Christian-based one where young men are being engaged from throughout the city and come here.

SUMMERS: Dr. Al Stokes is part of Clergy United to Transform Sandtown. His organization coordinates the youth sports at the park just across the street from the rec center, among some other initiatives. The church he leads is in Sandtown, but he’s now living in a different neighborhood in Northwest Baltimore, something that gives him perspective.

AL STOKES: I’ve got four different places I can go and buy bread or meat or shop at. There’s no place down here. We’re in USA. We’re in Maryland, a wealthy state. We’re in Baltimore. We have the Ravens. We have the Orioles. And you mean to tell me we have no place to shop for and no place that our seniors can shop? That’s deplorable.

SUMMERS: Still, Baltimore City Councilman James Torrence tells me that part of his job is showing members of this community that their government can meet their needs. Take the rec center, for example.

TORRENCE: People think they’re left behind, so the apathy for people is high, but it’s also getting the trust so that they come back out and trust us. The fact that they were a little scared when we told them, tell us what you want for your rec center. They’re like, what’s the budget? Dream.

SUMMERS: And the input from Sandtown, Torrence says, is the reason that, for now, plans are on track to bring the rec center back.

TORRENCE: There’s been a consistent voice among the Black women that are leading this movement in this neighborhood that, we want this thing and this is how we want it. And when I say they leave no room without a commitment – every time I met with them, a commitment was made, and it had to be followed through. And then I think that’s the next thing – it is about to follow through.

SUMMERS: Torrence says the city hopes to start building a $26 million new facility by 2027.

MALONE: This community still needs to heal, and how do we heal besides coming together? We are creating hope here in Sandtown. Regardless of all the money that came that did not stay here in Sandtown, Sandtown still thrives.

SUMMERS: And part of Tracey Malone’s hope is that a new rec center can create the same kind of connection for a new generation of Sandtown’s young people that she found decades ago.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

The airspace around El Paso is open again. Why it closed is in dispute

The Federal Aviation Administration abruptly closed the airspace around El Paso, only to reopen it hours later. The bizarre episode pointed to a lack of coordination between the FAA and the Pentagon.

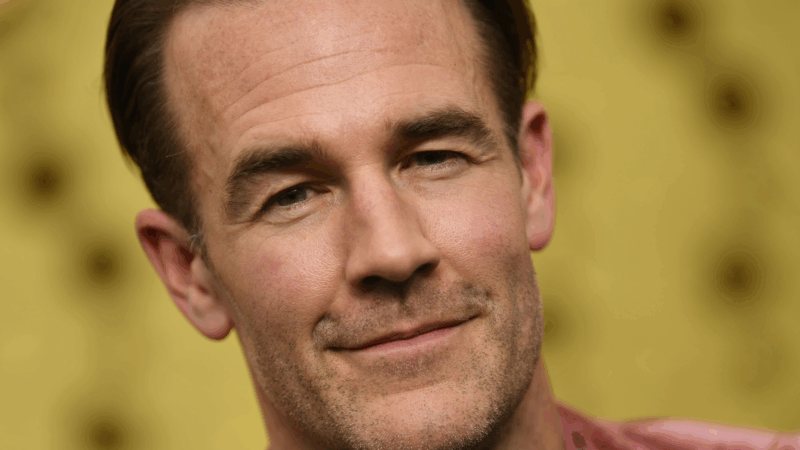

‘Dawson’s Creek’ star James Van Der Beek has died at 48

Van Der Beek played Dawson Leery on the hit show Dawson's Creek. He announced his colon cancer diagnosis in 2024.

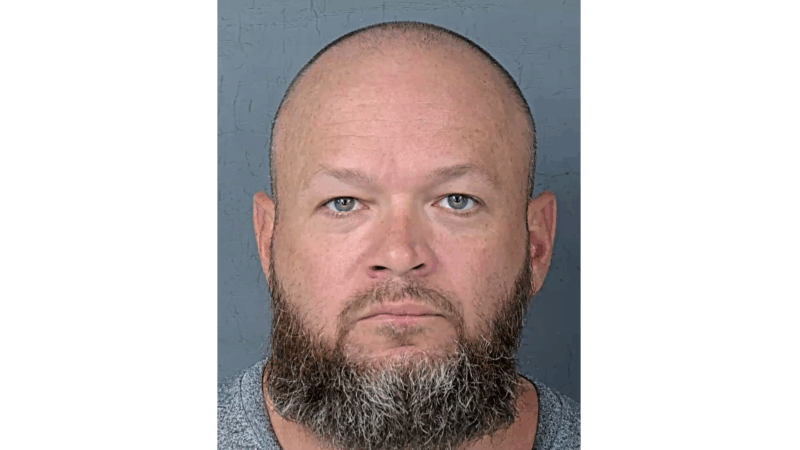

A Jan. 6 rioter pardoned by Trump was convicted of sexually abusing children

A handyman from Florida who received a pardon from President Trump for storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, was convicted on state charges of child sex abuse and exposing himself to a child.

A country-pop newcomer’s debut is your reinvention album of 2026

August Ponthier's Everywhere Isn't Texas is as much a fully realized introduction as a complete revival. Its an existential debut that asks: How, exactly, does the artist fit in here?

U.S. unexpectedly adds 130,000 jobs in January after a weak 2025

U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January as the unemployment rate dipped to 4.3% from 4.4% in December. Annual revisions show that job growth last year was far weaker than initially reported.

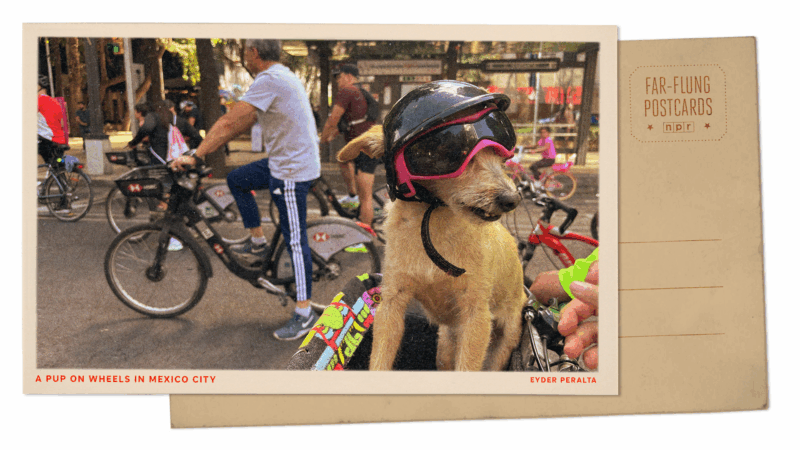

Greetings from Mexico City’s iconic boulevard, where a dog on a bike steals the show

Every week, more than 100,000 people ride bikes, skates and rollerblades past some of the best-known parts of Mexico's capital. And sometimes their dogs join them too.