Tariffs are fueling fears of a recession. What does it take to actually declare one?

The Trump administration’s new tariffs on imported goods from countries around the world have rattled consumers, stoked a trade war, roiled global markets and fueled widespread concerns about the prospect of a recession, both in the U.S. and globally.

In the days since President Trump announced the sweeping baseline and “reciprocal” tariffs, Google searches for the term “recession” have surged and economists at prominent investment banks have pointed to increased odds of a recession occurring.

In a Sunday note to clients, Goldman Sachs raised the probability of a U.S. recession from 35% to 45% — and that’s assuming the tariffs are rolled back. If the country-specific tariffs take effect Wednesday as intended, the firm says, “we would revise our forecast to include a recession.”

In a research report last week titled “There Will Be Blood,” JP Morgan upped its risk of a global recession to 60% from 40% before the tariff announcement.

Its CEO Jamie Dimon doubled down on Monday, writing in his annual letter to investors that the tariffs “will likely increase inflation” and are prompting “many to consider a greater probability of a recession.”

“Whether or not the menu of tariffs causes a recession remains in question, but it will slow down growth,” Dimon wrote.

There are growing calls for Trump to delay or reduce the tariffs coming from voices on Wall Street, Capitol Hill and around the world. Administration officials said Sunday that more than 50 countries have reached out to begin negotiations — but have also said the tariffs will not be postponed.

In an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Sunday, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent downplayed concerns about a recession, saying, “We’re going to hold the course.” Pointing to March’s better-than-expected jobs report, he said he sees “no reason that we have to price in a recession.”

“There doesn’t have to be a recession,” he added. “Who knows how the market is going to react in a day, in a week. What we are looking at is building the long-term economic fundamentals for prosperity.”

With all this talk about a potential recession, it’s worth taking a look at what the term actually means — and who decides when it applies.

What is a recession?

A recession refers to a period of decline in economic activity. It’s one of the four stages of the economic cycle: growth, peak, contraction (or recession) and trough.

Some analysts use a rough rule of thumb to identify recessions: Two consecutive quarters of decline in a nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) — the broadest measure of economic activity.

But the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) — the nonpartisan, nonprofit research organization that has become the semi-official arbiter of recessions — uses a somewhat squishier definition. It calls a recession a “significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.”

Who declares a recession?

The job of documenting the economic cycles, including recessions, does not fall to the federal government.

Instead, the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee — made up of top American economists — has been declaring the beginning and end of the cycles since its creation in 1978 (NBER itself is decades older).

There is no fixed rule about how long NBER takes to identify a recession after a decline has started. It says on its website that past determinations have taken anywhere from four to 21 months.

“We wait long enough so that the existence of a peak or trough is not in doubt, and until we can assign an accurate peak or trough date,” NBER says.

For example, it announced in June 2020 that the U.S. had officially entered a pandemic-induced recession months earlier, in February. It announced over a year later that the 2020 recession had ended in April after just two months, making it the shortest U.S. recession on record.

What happens in a recession?

A shrinking economy can cause a cascade of stressful ripple effects, including lower employment, deteriorating stock market results and higher borrowing costs for consumers and companies, according to Fidelity.

For example, people may not want to spend as much, which can impact the businesses they would otherwise support, which can lead to layoffs and in turn harm companies’ performance in the stock market — further fueling the cycle.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told NPR last week that consumer confidence and discretionary spending were already on the decline. He said the possibility of even broader tariffs — which were announced the following day — could speed up the path to a recession.

“It’s the consumer that’s feeling the brunt of it first, and with good reason,” he said. “But … the way you get to recession is businesses see the weakening in their sales, and if they start laying off workers, then we’re done. We’re going into a recession.”

How rare are recessions?

Various factors can jolt the economy into a recession, from unexpected events (like pandemics and wars) to asset bubbles bursting to excessive inflation or deflation.

The U.S. has experienced 34 recessions since 1857, according to NBER data.

They varied considerably in length, from two months (2020) to over five years (The Panic of 1873, which triggered the “Long Depression”).

Since World War II, the average length of a recession has been 11.1 months, according to the business publication Kiplinger. The post-WWII U.S. has averaged a recession every 6.5 years, it adds.

The longest post-WWII recession was the Great Recession, which spanned 18 months from December 2007 to June 2009 and was triggered when the U.S. housing bubble burst. The most recent was the brief COVID-19 recession in 2020. While the economy experienced two quarters of negative GDP growth in early 2022, fueling fears of a recession, NBER did not declare one.

Depressions are much more severe and rare: Merriam-Webster says they are characterized by widespread unemployment and major pauses in economic activity. NBER does not specifically identify depressions, but says the U.S. is generally regarded to have last experienced one in the 1930s.

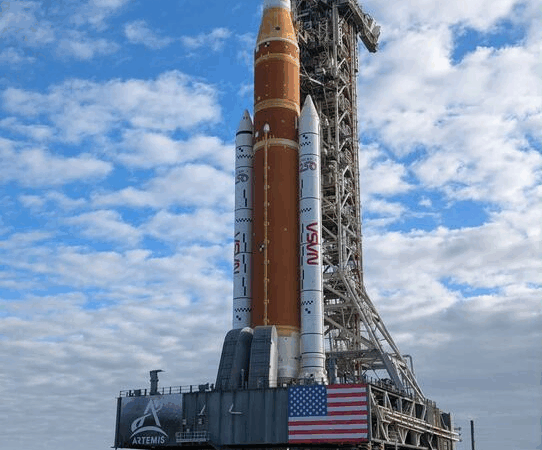

NASA rolls out Artemis II craft ahead of crewed lunar orbit

Mission Artemis plans to send Americans to the moon for the first time since the Nixon administration.

Trump says 8 EU countries to be charged 10% tariff for opposing US control of Greenland

In a post on social media, Trump said a 10% tariff will take effect on Feb. 1, and will climb to 25% on June 1 if a deal is not in place for the United States to purchase Greenland.

‘Not for sale’: massive protest in Copenhagen against Trump’s desire to acquire Greenland

Thousands of people rallied in Copenhagen to push back on President Trump's rhetoric that the U.S. should acquire Greenland.

Uganda’s longtime leader declared winner in disputed vote

Museveni claims victory in Uganda's contested election as opposition leader Bobi Wine goes into hiding amid chaos, violence and accusations of fraud.

Opinion: Remembering Ai, a remarkably intelligent chimpanzee

We remember Ai, a highly intelligent chimpanzee who lived at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for most of her life, except the time she escaped and walked around campus.

The near death — and last-minute reprieve — of a trial for an HIV vaccine

A trial was about to launch for a vaccine that would ward off the HIV virus. It would be an incredible breakthrough. Then it looked as if it would be over before it started.