Supreme Court hears case that could see more Planned Parenthood clinics closed

The U.S. Supreme Court seemed closely divided on Wednesday in a case testing whether states can remove Planned Parenthood clinics from state Medicaid programs — even though Medicaid cannot generally be used to fund abortions.

Under the Medicaid law, the federal government provides the lion’s share of Medicaid funding for all fifty states. In exchange, the states must meet a variety of requirements. One of those is that Medicaid patients are entitled to choose their doctors. In the words of the statute, they are entitled to treatment from “any qualified [and willing] provider.”

In South Carolina, that includes Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, which provides low-income patients with many run-of-the-mill services, from cancer screenings to full physical exams.

But in 2018, the state’s Republican governor issued executive orders terminating Planned Parenthood from participating in the Medicaid program. Those orders were repeatedly blocked by the lower courts, prompting South Carolina to appeal.

Planned Parenthood has long trumpeted the fact that it provides health care in all fifty states. But this case could end that nationwide footprint, if the Supreme Court rules in favor of South Carolina.

On Wednesday, the question before the Supreme Court was whether individuals can go to court at all to vindicate their right to choose their doctors under the Medicaid law.

Lawyer John Bursch, representing South Carolina, argued that the Medicaid statute does not mention the word “right” or its “functional equivalent,” and thus individuals have no right to sue to enforce the choice-of-doctor provision.

Justice Elena Kagan wasn’t buying that argument. “The state has an obligation to ensure that a person—I don’t even know how to say this—without saying ‘right’—has the right to choose their doctor,” she said.

Kagan noted that the U.S. Congress specifically amended the Medicaid law to ensure the freedom to choose one’s doctor under Medicaid. “That’s what this provision is. It’s impossible to even say the thing without using the word right,” she said.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked what recourse she would have if she wanted to see Dr. Jones, a fully qualified provider, but the state wouldn’t cover the charges because Dr. Jones was at Planned Parenthood. Couldn’t she sue to enforce her choice of physician? In that scenario, “you’re depriving me of my ability… to see the provider of my choice,” she suggested.

Bursch, the lawyer for the state, replied that patients don’t have a “magic wand” allowing them to pick their doctor.

Questions about flood of lawsuits

In states where abortion is banned or severely restricted, Planned Parenthood is able to remain in business largely because its clinics provide non-abortion services, and Medicaid covers much of the costs for low-income patients.

Wednesday’s case has implications beyond South Carolina. If the Supreme Court rules for the state of South Carolina in this case, Planned Parenthood would likely have to close its doors in the state, and the ripple effects would be profound, spreading to many other states where politicians have long tried to make it impossible for Planned Parenthood to provide non-abortion services.

If, on the other hand, the court rules in favor of Planned Parenthood, it can continue to provide the same medical services for low-income people, and be reimbursed by Medicaid for most of the costs.

Representing Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, lawyer Nicole Saharsky told the justices that Congress clearly established an individual right in the law — a right that the state cannot abridge, and that an individual may sue to enforce.

Questioned by Justice Samuel Alito about the potential for a flood of lawsuits, she pointed to the dozens and dozens of provisions imposed on the state under the Medicaid law. She noted that only eight or nine of them are, by law, enforceable by individuals. Yet none has led to a flood of lawsuits.

From there she pivoted to a different point, the state’s contention that Medicaid’s “any qualified provider” provisionhas led to lawyers gobbling up legal fees or patients somehow profiting from these this lawsuits.

“It’s wrong to suggest that individuals on Medicaid are seeking… some kind of financial benefit,” she said.

They are not seeking monetary damages, she observed. All they want is a court order allowing Planned Parenthood, a qualified Medicaid provider, to remain in the state, where it has operated for decades, treating principally low-income patients.

“These aren’t people getting rich,” said lawyer Saharsky. “They’re just trying to get healthcare.”

A decision in the case is expected in June.

US launches new retaliatory strike in Syria, killing leader tied to deadly Islamic State ambush

A third round of retaliatory strikes by the U.S. in Syria has resulted in the death of an Al-Qaeda-affiliated leader, said U.S. Central Command.

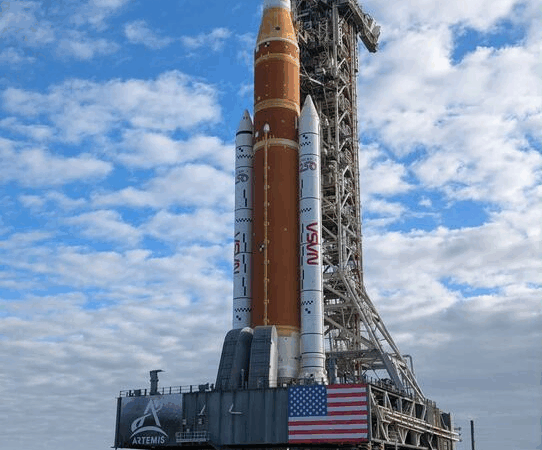

NASA rolls out Artemis II craft ahead of crewed lunar orbit

Mission Artemis plans to send Americans to the moon for the first time since the Nixon administration.

Trump says 8 EU countries to be charged 10% tariff for opposing US control of Greenland

In a post on social media, Trump said a 10% tariff will take effect on Feb. 1, and will climb to 25% on June 1 if a deal is not in place for the United States to purchase Greenland.

‘Not for sale’: massive protest in Copenhagen against Trump’s desire to acquire Greenland

Thousands of people rallied in Copenhagen to push back on President Trump's rhetoric that the U.S. should acquire Greenland.

Uganda’s longtime leader declared winner in disputed vote

Museveni claims victory in Uganda's contested election as opposition leader Bobi Wine goes into hiding amid chaos, violence and accusations of fraud.

Opinion: Remembering Ai, a remarkably intelligent chimpanzee

We remember Ai, a highly intelligent chimpanzee who lived at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for most of her life, except the time she escaped and walked around campus.