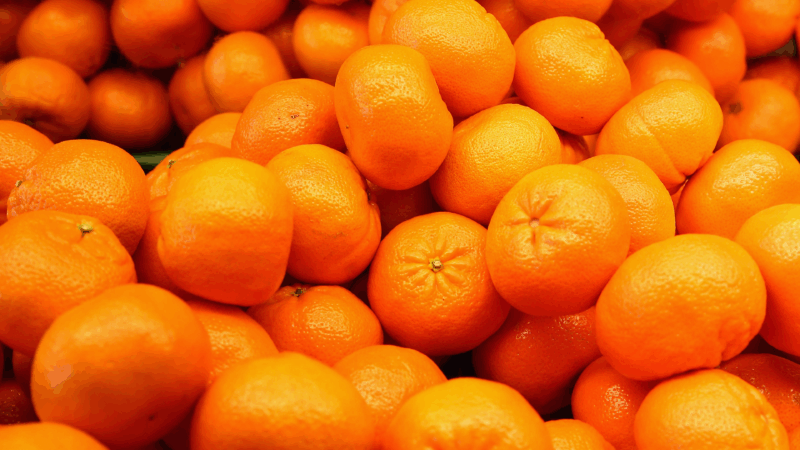

Supermarket displays of oranges will never look the same after reading ‘Foreign Fruit’

In a modern supermarket, shiny globes of oranges are stacked in pyramids. They appear identical and in their seeming perfection, unremarkable, a mundane fruit to slice into wedges and pack in a child’s lunchbox.

But as Katie Goh unravels in Foreign Fruit: A Personal History of the Orange, underneath its pitted skin, the orange contains multitudes. “Citrus is fruit that freely betrays,” Goh writes. “Plant a seed from an orange and any of the fifteen hundred species of the Rutaceae family, commonly called the citrus family, could grow from its burial place.”

Humans have stepped in to curb the citrus family’s tendency to cross-pollinate by grafting branches from trees they wish to replicate on sturdy rootstock, ensuring the consistent production of one kind of fruit. But as anyone who has snacked on clementines and tasted differing levels of sweetness and acidity from fruit to fruit knows, attempts at control can only go so far. As Goh explains, the orange “is a fruit born with inherent divergence in its genes.”

It is this unrepentant multiplicity that spurred Goh to look deeper at the orange in Foreign Fruit, an elegant hybrid memoir about hybridity that pulls apart mythologies of colonialism, inheritance and identity like the segments of a citrus fruit. Like the orange, Goh is multiple: She is a queer person of Chinese, Malaysian and Irish heritage who was raised in Northern Ireland. And like the orange, her family’s history comprises “ancestral roots in China that venture towards the equator, and then traverse the long roads from east to west to reach Europe.” In retracing that history, Goh refuses simple stories, instead conjuring a complex, finely woven exploration of the citrus and the self.

Goh began peeling back layers in March 2021, when a 21-year-old white man killed eight people, six of them Asian women, in shootings at two spas in the Atlanta area. The next morning, Goh received a query from an editor with the subject line “Asian hate crimes?,” asking for an 800-word piece on the shootings from her perspective. Instead of accepting the commission, Goh writes that she sat down at her parent’s kitchen table near Belfast and ate five oranges, “fistfuls of flesh” that left her jaw aching and her body “hot and heavy and full.”

Eating those five oranges in that moment of pain and frustration led Goh to see the fruit anew and pointed her toward a new method of self-expression. She had begun her writing career while in college in the 2010s, at the height of what critic Laura Bennett termed the “first-person industrial complex,” where women were encouraged to commodify traumatic experiences by packaging them in essays designed to go viral. After a childhood in 99% white Northern Ireland, where self-curtailment felt mandated, Goh embraced “the opportunity to break into journalism and to cauterize the past” by writing about her racial identity. But the “persona” she crafted on the page, with “convenient” and “neat” narrative arcs, she writes, had emptied her out like an orange extracted for every last bit of juice and oil.

In Foreign Fruit, Goh turns oranges into a cipher, a way of writing about herself indirectly through a refracted lens that explodes the clean narratives she once reduced herself to. Each chapter braids together citrus’s historical path across the globe with Goh’s personal travels, family history, and meditations on hybridity. Both journeys begin in China, where sweet oranges were first cultivated and where a teenage Goh visits her father’s ancestral village in Fujian, seeking “authenticity” and a sense of easy belonging that eludes her. Goh then traces how oranges transitioned from native to foreign as they became commodities along the Silk Roads, examining this multifarious lineage in parallel to her own family tree, which she constructed during a 2019 stay with her grandparents in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Trips to the Netherlands and Austria mirror the orange’s path through European empires, sparking analysis of how colonization impacted her own life, from Britain’s conquering of Malaysia to the education she received in Northern Ireland that “polished” Britain’s complex history “into a tale of empire, royalty, and greatness that was taken as truth.”

Throughout, finely detailed cinematic present-tense descriptions of historical scenes plunge readers into the past, showcasing Goh’s talents as a prose stylist. In this, Foreign Fruit sidesteps a common pitfall of hybrid memoir, where the inquiry into the outside world can be less compelling than the personal journey. Yet as the book progresses, Goh’s choice to construct that personal journey around literal journeys hamstrings opportunities for sustained reflection. Toward the end of the book, for instance, Goh recounts a trip to Kuala Lumpur to celebrate the Lunar New Year with family, where she learns of yet another mass shooting with multiple Asian victims, this time committed by an Asian man in a dance hall in Southern California. But her tearful meditations that night are interrupted by the sound of celebratory fireworks, cutting her reflections off at the surface.

While Goh has stopped “crushing [her]self to tell a convenient story,” using the orange as a “model for hybrid existence” only gets her so far in Foreign Fruit. Yet the journey offers much food for thought, and readers will never see supermarket displays of oranges the same way again.

Kristen Martin is the author of The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow: The Dark History of American Orphanhood. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New York Review of Books, the Washington Post, and elsewhere.

Alabama Power seeks to delay rate hike for new gas plant amid outcry

The state’s largest utility has proposed delaying the rate increase from its purchase of a $622 million natural gas plant until 2028.

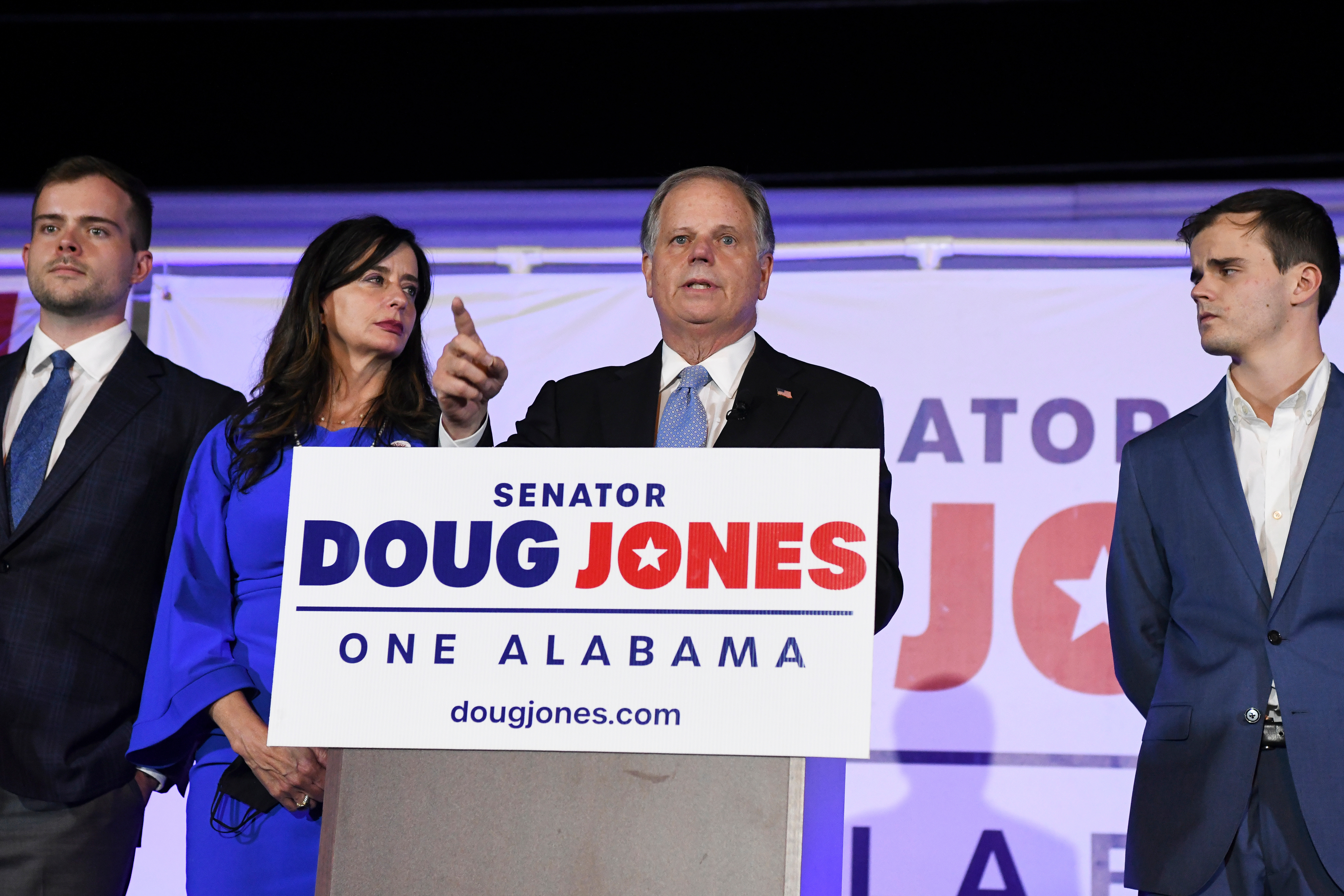

Former U.S. Sen. Doug Jones announces run for Alabama governor

Jones announced his campaign Monday afternoon, hours after filing campaign paperwork with the Secretary of State's Office. His gubernatorial bid could set up a rematch with U.S. Sen. Tommy Tuberville, the Republican who defeated Jones in 2020 and is now running for governor.

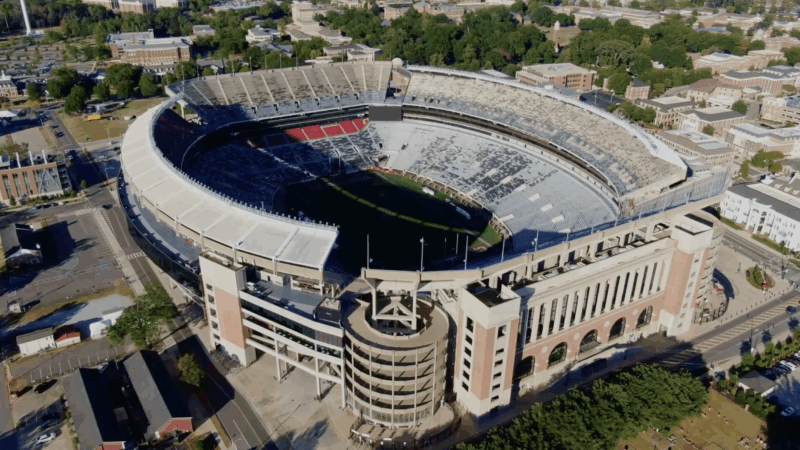

Scorching Saturdays: The rising heat threat inside football stadiums

Excessive heat and more frequent medical incidents in Southern college football stadiums could be a warning sign for universities across the country.

Judge orders new Alabama Senate map after ruling found racial gerrymandering

U.S. District Judge Anna Manasco, appointed by President Donald Trump during his first term, issued the ruling Monday putting a new court-selected map in place for the 2026 and 2030 elections.

Construction on Meta’s largest data center brings 600% crash spike, chaos to rural Louisiana

An investigation from the Gulf States Newsroom found that trucks contracted to work at the Meta facility are causing delays and dangerous roads in Holly Ridge.

Bessemer City Council approves rezoning for a massive data center, dividing a community

After the Bessemer City Council voted 5-2 to rezone nearly 700 acres of agricultural land for the “hyperscale” server farm, a dissenting council member said city officials who signed non-disclosure agreements weren’t being transparent with citizens.