Sumy, a center of Ukrainian culture, lives in the crosshairs of a new Russian offensive

SUMY, Ukraine — That terrible Sunday keeps replaying in Natalia Tsybulko’s head. The huge explosions. The frantic calls to find her daughter. The words from her son-in-law that shattered her life.

“‘Mom, Olena is no longer with us’,” Tsybulko recalled him saying when he called, his voice ragged. “He was holding her body in his arms.”

Olena Kohut, her 46-year-old daughter, was killed in a Russian missile attack here in April. She was the organist of the local philharmonic and something of a celebrity in Sumy, a northern Ukrainian regional capital with a history of music and resistance, about 15 miles from the Russian border.

“You think you’ve been hardened by this war, it’s been going on so long,” Tsybulko says. “And then it takes the very light of your life.”

Like many Ukrainian cities, Sumy has been scarred by war. It saw heavy fighting early in the full-scale invasion and has, in the last year, become a frequent target of Russian drones, missiles and guided bombs. Now, Ukraine’s top general, Oleksandr Syrsky, says at least 50,000 Russian troops have massed on the other side of the border, though Ukraine has so far managed to thwart them.

Loading…

“You’re alive!”

Sumy sits on the banks of the Psel River, and even now, despite regular attacks, locals fill the leafy riverside promenade when the weather is warm and sunny. They used to flock to music festivals on Bach and brass bands before the war. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion, many of Sumy’s authorities fled, and residents defended the city on their own.

“We are friendly but tough,” said acting mayor Artem Kobzar. “We don’t back down.”

In the last year, Kobzar said, the city of Sumy has become a magnet for those who live in greater Sumy — villages on the Russian border, where attacks are more frequent. Newspaper publisher Natalia Kalinichenko is from Biliopillia, a village in the region less than 4 miles from the Russian border. Kalinichenko now lives part-time in Sumy, though the newspaper she runs is still delivered to those remaining in the village.

“In many villages along the border, there is often no electricity or internet,” she said. “And the printed copy of a newspaper is often the only source of information for people.”

The region of Sumy borders Russia’s Kursk region. Last summer, Ukraine launched a surprise incursion into Kursk. The operation was intended to distract Russia and pull Russian troops from vulnerable sections of the eastern frontline. As Russian troops slowly clawed back most of Kursk, attacks on Sumy – and its regional capital, Sumy city – increased.

In one attack in late January, Russian drones hit an apartment complex in an overnight attack, killing nine people and injuring 13. Smoke and dust filled the air as stunned residents ran out of the broken building, bundling their cats and dogs inside their coats and bathrobes, and calling their neighbors.

“You’re alive!” one woman screamed in relief into her cell phone.

Anton Svachko, a member of Ukraine’s parliament from the city, drove to the scene immediately after he heard the news.

“We need more air defense, we need more air defense units, we need more everything,” he told NPR, rubbing his eyes as he surveyed the damage.

Standing next to him was the acting mayor, Kobzar, who comforted two siblings who couldn’t find their relatives and a family whose home was destroyed.

“The people whose homes have been struck, the first thing they ask me is, ‘how quickly can my home be rebuilt?'” Kobzar said.

Volodymyr Silvanovskyi, a 63-year-old customs official, shook his head after he found out his neighbors, a couple in their 60s, had been killed, crushed inside their own apartment. As he ran out, he saw their entire apartment had caved in.

“We stay because we don’t have anywhere to go,” he said, his voice breaking. “We have poured our lives into these homes.”

At the time of the strike, President Trump had recently been inaugurated, and Valentina Taran, a 65-year-old retiree who lived in the apartment complex, was hopeful. She had grown disillusioned with the Biden administration’s approach to Ukraine, which she described as “helping us just enough to survive but not much more.” She said she expected Trump to be more decisive.

“I just wish he could stop this war,” she said, “but I don’t know if he knows how.”

An ally turns

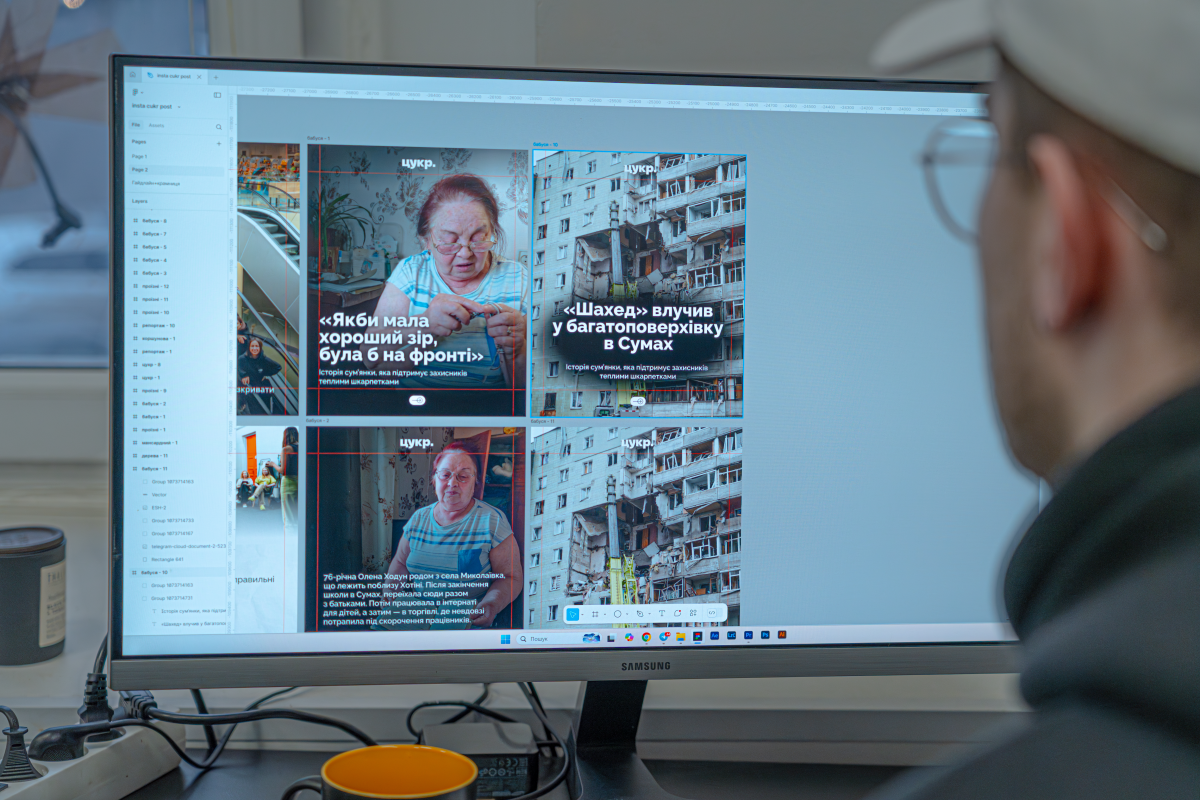

The morning after the strikes, the newsroom of Cukr, a local online magazine focused on community news, was buzzing.

The name comes from a shortened version of the Ukrainian word for sugar. “The city was once a main producer of sugar,” said Dmytro Tyshchenko, the outlet’s editor. “That was a long time ago, but we like the name.”

Cukr tries to focus on upbeat news, Tyshchenko said, adding that “we want to encourage people to take pride in our city.” The frequent Russian attacks, however, are often on the front page. When NPR visited the newsroom earlier this year, the attack was the main news on Cukr’s homepage, along with a trending profile about a woman who makes socks for Ukraine’s military.

“We are here to challenge Russian propaganda and the constant depressive situation of war,” Tyshchenko said, as we walked into the newsroom. “We live in this city and we want people to know it, and to know each other.”

Inside, communications manager Anna Olshanska was pacing. The strike hit the neighborhood where she grew up.

“My parents live there, and they’re OK, thank God,” she said. “It was a very stressful morning.”

The morning was also stressful for another reason: The Trump administration had frozen U.S. Agency for International Development funds, including money that helped support Ukraine’s independent media. Until then, Cukr received 60% of its money from USAID, according to Tyshchenko.

“It’s hitting small media like us the worst,” he said. “We don’t have time to worry about it. We are trying to be optimistic about surviving without this help.”

Russian attacks in Sumy continued as Ukraine suddenly faced an unreliable relationship with the U.S., once its strongest individual ally.

The Trump administration began dismantling USAID, a huge blow to Ukraine, the agency’s top recipient as of 2023, the last year in which data is available. Agency funds did much more than subsidize independent media. The money supported Ukraine’s farmers, veterans and tech workers, and also helped the country repair its energy grid, badly damaged by Russian attacks.

Trump and his top aides also berated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy when he visited the Oval Office on Feb. 28 and repeated Russian talking points. After that, the White House abruptly cut off military aid to Ukraine, as well as intelligence sharing. The aid cut-off lasted about a week, until talks between Ukraine and the U.S. in Saudi Arabia on March 11, when Ukraine agreed unconditionally to a U.S.-brokered ceasefire to last 30 days.

Russia did not sign on, however, and after that began escalating attacks on Ukrainian cities.

A bloody Sunday

On April 13, Palm Sunday, 13-year-old Kyrylo Illiashenko was on a bus in downtown Sumy with his mom, Maryna. They were headed to his grandmother’s house and after that he had wrestling practice.

He held his gym bag on his lap as his mom talked on the phone to his grandmother about Sunday lunch. Then the boy heard a strange whistling sound.

“And then an explosion,” he said. “I was knocked down and felt broken glass cutting me.” The glass shards also sliced his mother’s face. The bus filled with black smoke.

A Russian ballistic missile had hit nearby. People on the bus shouted for the driver to open the door.

“But the driver was dead,” Kyrylo said.

(Evgeniy Maloletka | AP)

He couldn’t find his mom and worried the bus would explode. A broken window was the only exit. He hurled his gym bag through the window, then jumped through himself.

Outside, he saw bodies on the street. He rushed back to the bus and forced the door open. He pulled out the gasping passengers, including his mom. Later, his eighth-grade classmates thanked him for saving their relatives on that bus.

“You’re a hero,” they texted him.

Nadia Hryn, who runs Sumy’s music conservatory, heard the town’s philharmonic building had also been hit. She knew her friend Olena Kohut, the philharmonic’s organ soloist, was on her way to rehearsal there. Kohut also taught piano at the conservatory.

“I heard the first explosion and called Olena right away,” Hryn said. “She didn’t answer.”

Kohut’s best friend, Ella Mykhaylova, a violinist, called her too, several times, but couldn’t get through. Then she got a call from the philharmonic’s percussionist.

“He told me she had called him after the first explosion and said there were many people lying on the street,” Mykhaylova said. “She wanted to help them. Then there was a second explosion, so he ran to find her.”

A second ballistic missile had hit, just a few minutes after the first. He found her on the ground, not moving. Emergency workers tried to resuscitate her for an hour before giving up.

She was among 35 people killed that day. More than 100 were injured.

Kohut’s students left bouquets wrapped in sheet music at the site of the attacks.

The grieving mother

Kohut’s mother, Natalia Tsybulko, is a classically trained singer who also teaches at the conservatory. She has returned to the classroom alone. Her daughter’s absence haunts her.

“When she was a baby, I took her to all my concerts,” Tsybulko said. “When she grew up and fell in love with the piano, she accompanied me when I sang.”

As she listened to a student sing Italian arias – her daughter’s favorite – she struggled to compose herself. After class, Tsybulko sat in the back, scrolling through her phone to find videos of her daughter’s organ performances.

“When she sat down to play that organ, she made it sing like a voice,” Tsybulko said, her voice hoarse.

She wiped away tears and walked upstairs to meet Hryn, the conservatory director. In her office, Hryn set out cups of coffee spiced with pepper, cardamom and a few drops of strong Slovak liquor. She sat next to the grieving mother and stroked her hand.

“The horror and cruelty, we feel it every day,” Hryn said. “We tell each other, ‘have a safe day, a safe night, a quiet night’. And then we go to funerals. Everything is fragile.”

Kohut’s family and friends held a memorial concert for her on May 21 in a candlelit hall. The concert opened with a billboard-size screen showing a video of Kohut in a black, glittery full-length gown, playing “Chariots of Fire” by Vangelis. A performance by Kohut’s students and the philharmonic orchestra followed.

“She flew her short life,” said Hryn, “on the wings of music.”

Transcript:

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

The Easter ceasefire the Kremlin announced has not held, according to statements online by both the Russian Defence Ministry and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. In a separate Easter message, Zelenskyy reflected on deadly missile attacks on Kharkiv, Dnipro, Odessa and a Palm Sunday strike on Sumy that killed at least 35 people. From Sumy, here’s NPR’s Joanna Kakissis.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

JOANNA KAKISSIS, BYLINE: In the lobby of Sumy’s local music college, there’s a memorial to Olena Kohut, killed on Palm Sunday at age 46. A framed portrait shows a woman with thick chestnut hair and a Mona Lisa smile. Nearby, a TV plays a video of Kohut performing an organ solo.

NATALYA TSYBULKO: This is my Olenychka (ph).

KAKISSIS: “My Olenychka,” says her mother, Natalia Tsybulko (ph), using her daughter’s childhood nickname.

TSYBULKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “She had such a touch,” Tsybulko says. “When she sat down to play that organ, she made it sing like a voice.”

Tsybulko is a slight woman in her 70s and a classically trained singer. When her only daughter was born, she brought the baby to all her concerts.

TSYBULKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “And when she was a year and 7 months old,” she says, “I remember pushing her stroller and suddenly hearing…”

TSYBULKO: (Singing in Russian).

KAKISSIS: Her baby daughter was singing, loud and clear. As a child, her daughter fell in love with the piano and the organ. She grew up to become a soloist with the local philharmonic. She was featured last year in this Ukrainian documentary about the sounds of Sumy.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

KAKISSIS: She talked about mixing contemporary and classical music.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

OLENA KOHUT: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “So why experiment?” she told the interviewer. “Because we want to encourage people to listen.”

Kohut also taught classes at the music college, where her mother is a longtime vocal teacher.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS)

KAKISSIS: Her mother returns to the classroom alone.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT: (Singing in Italian).

KAKISSIS: As a student sings an Italian aria, Tsybulko wipes away tears, remembering her daughter.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT: (Singing in Italian).

TSYBULKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “We performed Italian arias together all the time,” she says, covering her face.

NADIA HRYN: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: After class, Nadia Hryn, who runs the music college, comforts Tsybulko. She makes the grieving mother a coffee spiced with pepper, cardamom and a few drops of strong Slovak liquor.

HYRN: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “The horror and the cruelty, we feel it every day,” Hryn says, referring to Russian attacks. “We tell each other to have a safe day, a safe night, a quiet evening.”

Tsybulko says the day her daughter was killed runs like a loop through her head.

TSYBULKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “My son-in-law calling me and weeping, Mom, Olena is no longer with us,” she says. He was holding her body in his arms. She cannot bear her daughter’s absence, so she finds a video on her phone…

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

KAKISSIS: …Of her daughter playing a piano solo.

TSYBULKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “Beautiful music,” she says. “Such beautiful music.”

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED MUSICAL ARTIST: (Singing in non-English language).

KAKISSIS: Joanna Kakissis, NPR News, Sumy, Ukraine.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.