State laws to stop surprise ambulance bills face pushback from insurers

Nicole Silva’s 4-year-old daughter was headed to a relative’s house near the southern Colorado town of La Jara when a vehicle T-boned the car she was riding in. A cascade of ambulance rides ensued — a ground ambulance to a local hospital, an air ambulance to Denver, and another ground ambulance to Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Silva’s daughter was on Medicaid, which was supposed to cover the cost of the ambulances. But one of the three ambulance companies, Northglenn Ambulance, a public company since acquired by a private one, sent Silva’s bill to a debt collector. It was for $2,181.60, which grew to more than $3,000 with court fees and interest, court records show.

The preschool teacher couldn’t pay, and the collector garnished Silva’s wages. “It put us so behind on bills — our house payment, electric, phone bills, food for the kids,” said Silva, whose daughter recovered fully from the 2015 crash. “It took away from everything.”

Some state legislators are looking to curb bills like the one she received — surprise bills for ground ambulance rides.

When an ambulance company charges more than an insurer is willing to pay, patients can be left with a big bill they probably had no choice in.

States are trying to fill a gap left by the federal No Surprises Act, which covers air ambulances but not ground services, including ambulances that travel by road and water. This year, Utah and North Dakota joined 18 other states that have passed protections against surprise billing for such rides.

Those protections often include setting a minimum for insurers to pay out if someone they cover needs a ride. But the sticking point is where to set that bar. Legislation in Colorado and Montana stalled this year because policymakers worried that forcing insurers to pay more would lead to higher health coverage costs for everyone.

Surprise ambulance bills are one piece of a health care system that systematically saddles Americans with medical debt, straining their finances, preventing them from accessing care, and increasing racial disparities, as KFF Health News has reported.

“If people are hesitating to call the ambulance because they’re worried about putting a huge financial burden on their family, it means we’re going to get stroke victims who don’t get to the hospital on time,” said Patricia Kelmar, who directs health care campaigns at PIRG, a national consumer advocacy group. “It means that person who’s worried it might be a heart attack won’t call.”

Challenges to passing protections in Colorado

The No Surprises Act, signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2020, says that for most emergency services, patients can be billed for out-of-network care only for the same amount they would have been billed if it were in-network. Like doctors or hospitals, ambulance companies can contract with insurers, making them in-network. Those that don’t remain out-of-network.

But unlike when making an appointment with a doctor or planning a surgery, a patient generally can’t choose the ambulance company that will respond to their 911 call. This means they can get hit with large out-of-network bills.

Federal lawmakers punted on including ground ambulances, in part because of the variety of business models — from private companies to volunteer fire departments — and a lack of data on how much rides cost.

Instead, Congress created an advisory committee that issued recommendations last year. Its overarching conclusion — that patients shouldn’t be stuck in the crossfire between providers and payers — was not controversial or partisan. In Colorado, a measure aimed at expanding protections from surprise ambulance bills got a unanimous thumbs-up in both legislative chambers.

Colorado had previously passed a law protecting people from surprise bills from private ambulance companies. This new measure was aimed at providing similar protections against bills from public ambulance services and for transfers between hospitals.

“We knew it had bipartisan support, but there are some people that vote no on everything,” said a pleasantly surprised Karen McCormick, a Democratic state representative.

A less pleasant surprise came later, when Gov. Jared Polis, who is also a Democrat, vetoed it, citing the fear of rising premiums.

States can do only so much on this issue, because state laws apply only to state-regulated health plans. That leaves out a lot of workers. According to a 2024 national survey by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News, 63% of people who work for private employers and get health insurance through their jobs have self-funded plans, which aren’t state-regulated.

“It’s why we need a federal ambulance protection law, even if we passed 50 state laws,” Kelmar said.

According to data from the Colorado secretary of state’s office, the only lobbying groups registered as “opposing” the bill were Anthem and UnitedHealth Group, plus UnitedHealth subsidiaries Optum and UnitedHealthcare.

As soon as the legislative session ended in May, Kevin McFatridge, executive director of the Colorado Association of Health Plans, a trade group representing health insurance companies in the state, sent a letter to the governor requesting a veto, with an estimate that the legislation would result in premiums rising 0.4%.

The Colorado bill said local governments — such as cities, counties, or special districts — would set rates.

“We are in a much better place by not having local entities set their own rates,” McFatridge told KFF Health News. “That’s almost like the fox managing the henhouse.”

Resistance from the insurance industry

Jack Hoadley, an emeritus research professor with Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, said it isn’t clear whether state laws approved elsewhere are raising premiums, or if so by how much. Hoadley said Washington state is expected to come out with an impact analysis of its law in a couple of years.

The national trade association for insurance companies, AHIP, declined to provide a comment for this article. Instead, AHIP forwarded letters that its leaders submitted to lawmakers in Ohio, West Virginia, and North Dakota this year opposing measures in each state to set base ambulance rates. AHIP leadership described the proposals as inflated, government-mandated pricing that would reduce insurers’ chance to negotiate fair prices. Ultimately, the association warned, the proposed minimums would increase health care costs.

In Montana, legislators were considering a minimum reimbursement for ground ambulances of 400% of what Medicare pays, or at a set local rate if one exists. The proposal was sponsored by two Republicans and backed by ambulance companies. Health insurers successfully lobbied against it, arguing that the price was too steep.

Sarah Clerget, a lobbyist representing AHIP, told Montana lawmakers in a legislative hearing that it’s already hard to get ambulance companies to go in-network with insurers, “because folks are going to need ambulance care regardless of whether their insurance company will cover it.” She said the state’s proposal would leave those paying for health coverage with the burden of the new price.

“None of us like our insurance rates to move,” Republican state Sen. Mark Noland said during a legislative meeting as a committee tabled the bill. He equated the proposed minimum to a mandate that could lead to people having to pay more for health coverage for an important but nonetheless niche service.

Colorado’s governor was similarly focused on premiums. Polis said in his veto letter that the legislation would have raised premiums between 73 cents and $2.15 per member per month.

“I agree that filling this gap in enforcement is crucial to saving people money on health care,” he wrote. “However, those cost savings are outweighed in my view by the premium increases.”

Isabel Cruz, policy director at the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, which supported the bill, said that even if premiums did rise, Coloradans might be OK with the change. After all, she said, they’d be trading the threat of a big ambulance bill for the price of half a cup of coffee per month.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

Nancy Guthrie case: How do families of missing people cope with the uncertainty?

When a loved one goes missing, relatives can feel guilty simply for eating, says Charlie Shunick, whose sister was kidnapped. Shunick now helps others navigate a nightmare "nobody is prepared for."

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

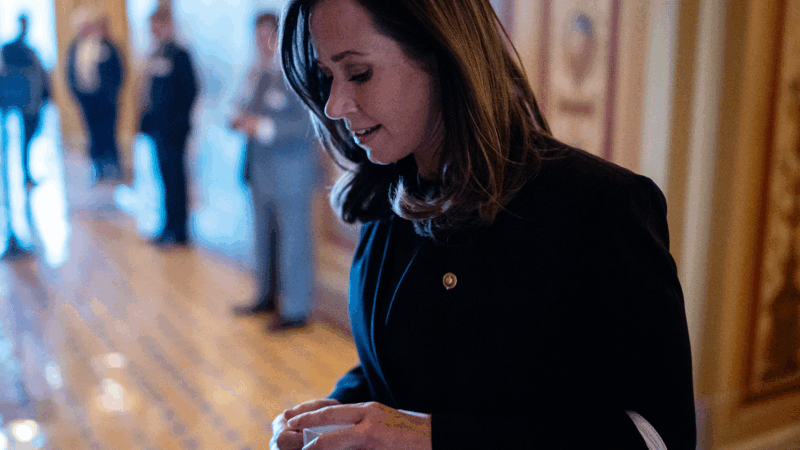

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

This community festival embraces the joys of a frozen lake — while it still has one

As climate change accelerates, local experts say the date Wisconsin's Lake Mendota freezes over is getting later, making safe conditions for activities that rely on snow and ice harder to predict.