Speaker Johnson slashed Medicaid. His constituents could lose health services

BOSSIER CITY, La. — The sweeping megabill pushed through Congress by House Speaker Mike Johnson could have some of its deepest consequences in his rural Louisiana district, where more than a third of residents are enrolled in Medicaid, according to data from the health information nonprofit KFF.

Thousands of residents who rely on the program that provides health coverage to low-income Americans could lose those benefits — and the federally qualified health centers that serve them could risk closure if they lose the current levels of revenue generated from Medicaid reimbursements.

Statewide, over 200,000 Louisianans could lose coverage under the law.

Constituent concerns

Some people who receive Medicaid now worry that even though they have occasional work, they may face challenges reporting their hours to meet the new work requirements. Under the law, adults ages 19 to 55 will be required to prove they are volunteering, receiving job training or working at least 80 hours each month to maintain coverage.

Jamie Collins is one of Speaker Johnson’s constituents who worries he won’t be able to meet the work requirements set to start in 2027. He recalls painting Johnson’s house in 2021. At the time, Johnson was a rising congressman from northwest Louisiana.

Collins has been out of work since last November and is now sleeping on the streets of Shreveport-Bossier City, the largest metropolitan area in Johnson’s district. He depends on Medicaid for prescriptions, doctor visits and dental care.

He followed the news and watched as Johnson pushed the legislation through Congress. Now, as he sits in a Shreveport homeless shelter to escape the sweltering heat that comes with August in Louisiana, he reflects on the time the man he knew then as his representative came through to inspect the paint job on his home.

“I mean, he liked the job,” Collins said. “But, I mean, how can you like a job with a person that’s performing work on your house, cutting Medicaid, that’s putting him in a bind?”

Across town, David Jackson prays for a breeze as he sits on his porch. His home doesn’t have air conditioning, and it’s cooler outside. Like Collins, Jackson is also on Medicaid and between jobs after leaving a landscaping gig that paid cash under the table and wasn’t reliable enough to pay his bills.

Jackson says he’s paid in cash and given the irregularity of his work, he’s concerned he wouldn’t meet the work requirements.

“What would I be able to do for myself? How can I get help?” Jackson says. “I can’t afford no doctor. I don’t have the money to afford no doctor.”

Johnson has defended the legislation at press events in his district over the summer recess, framing the changes as a way to crack down on “waste, fraud, and abuse.” His office declined NPR’s request for an interview.

“There’s a lot of misconceptions,” Johnson said at a July press conference in Bossier City. “This idea about how we’re cutting Medicaid and people are going to lose their health coverage is just simply not true.”

The changes to Medicaid are expected to generate nearly a trillion dollars in cuts, according to the Congressional Budget Office, which estimates 12 million people will lose their health care coverage.

Jackson’s seven-year-old son goes to a school-based clinic that’s part of the David Raines Community Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Bossier City. Jackson says his son has a speech impediment and the clinic at the school is the only way he’s able to see a doctor.

“They have helped me to get him to talking and sending him to extra centers and things like that,” Jackson says. “They are very helpful.”

Community health centers say they are on the brink of crisis

Louisiana expanded Medicaid in 2016 to cover more low-income adults, many of them unemployed or between jobs — like Jackson and Collins. The policy helped cut Louisiana’s uninsured rate in half and shored up rural hospitals that had been teetering on closure. Thirty-three of those hospitals are now at risk of closing under President Trump’s tax and spending megabill, further jeopardizing health care access in rural areas in Louisiana.

Now, not only could thousands of residents lose coverage, community health centers are bracing for a financial hit too.

In a mostly rural state, where poverty and chronic illness run deep, many depend on FQHCs for their care. Also called community health centers, FQHCs provide primary care, dental care, maternal health and behavioral health services in underserved areas to all patients, regardless of their ability to pay.

Last year, Louisiana’s network of these health centers served more than half a million patients, according to data from the Louisiana Primary Care Association.

Nationally, Medicaid reimbursements account for 42 percent of FQHC revenue, compared to just one-tenth from congressional funding. That balance means any pullback in Medicaid can push clinics into crisis.

Without additional funding from Congress to make up for anticipated shortfalls in revenue from Medicaid cuts, advocates say many FQHCs may be forced to shut down or reduce services.

“Right now a lot of health centers are having financial troubles and about 40 percent have less than 90 days cash on hand,” said Joe Dunn, chief policy officer of the National Association of Community Health Centers, which represents more than 13,000 FQHC sites across the country.

Can past bipartisan support lead to increased funding?

Congress faces a September 30 deadline to reauthorize funding for FQHCs. Historically, Dunn said, FQHCs have enjoyed bipartisan support. But this year, they’re advocating for an additional $1.2 billion to help offset the $7 billion clinics are projected to lose because of Medicaid cuts.

The chair of the committee that deals with FQHCs is Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Republican from Louisiana.

In a statement to NPR, Cassidy’s office said that he’s “committed to reauthorizing funding for community health centers on time, in a fiscally responsible manner” but did not indicate whether or not he would support additional funding.

Without that funding, Dunn warns the impacts could be severe.

“It certainly could lead to closures and, you know, loss of staff and things like that,” Dunn said.

For people in Johnson’s district who are struggling and between jobs, like Collins and Jackson, losing coverage and access to clinics could harm their ability to receive medical care. For Jackson, it could also mean losing the progress his son has made in overcoming a speech impediment — affecting the ability of a father and son to communicate.

Collins said he only exchanged simple pleasantries with Johnson back when he painted his house. But if he met him again today, he’d have more to say.

“I would actually ask him: ‘What’s the reason you’re cutting Medicaid,'” Collins said, “and hurting a lot of people in this city?”

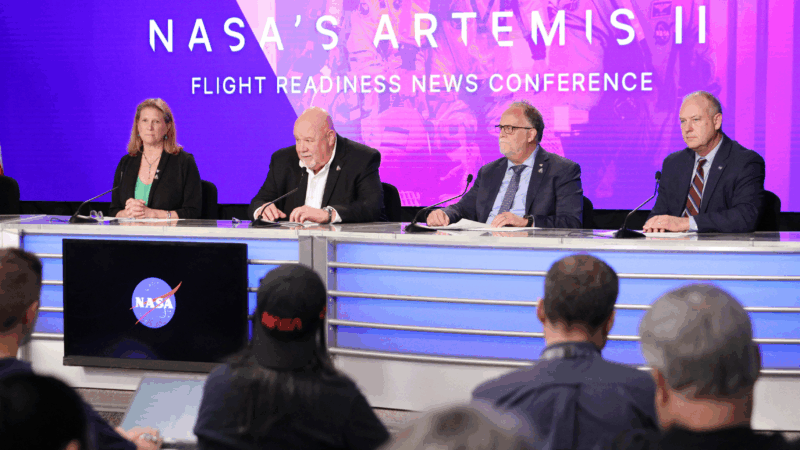

NASA targets Artemis II crewed moon mission for April 1 launch

A six-day launch window opens on April 1 from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The lunar orbital mission would be the first time humans have returned to the moon since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Auburn football player uses NIL funds to open a community hub in Birmingham

Jourdin Crawford, a freshman defensive lineman at Auburn, used earnings from a Name, Image, and Likeness deal to give back to his hometown.

Fear of Iranian mines in the Strait of Hormuz could further slow the flow of oil

Attacks by Iran have already nearly halted the flow of oil through the vital waterway as commercial ship crews fear being hit by missiles, drones or mines.

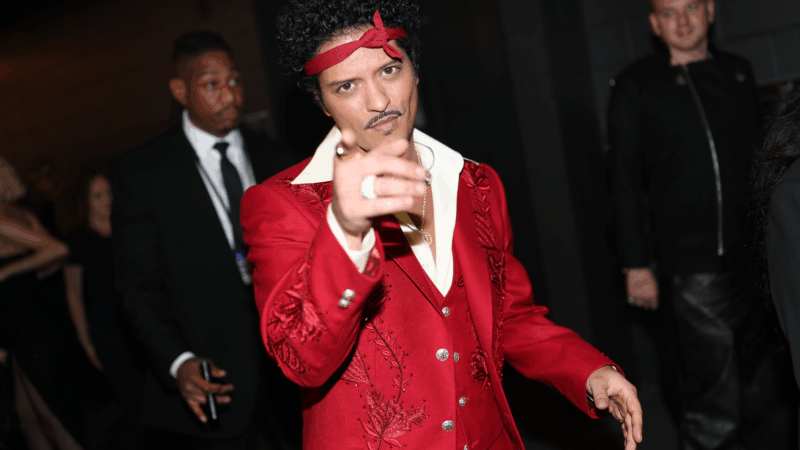

Bruno Mars adds yet another milestone to his career with ‘The Romantic’

Bruno Mars is the most-listened to artist in the world on Spotify. He's won 16 Grammys. In case you thought there were no battles left for him to win, this week he unlocked another achievement.

There’s more than one path to a confessional song

On new albums by viral sensation Yebba and studio whiz Pimmie, it's clear modern R&B has been clearing space for vastly different stripes of singer-songwriter.

Suspect in attack at Michigan synagogue is dead, officials say

Security officers at Temple Israel had "engaged the threat" that apparently started with a vehicle ramming into the building, according to Oakland County Sheriff Mike Bouchard.