Some ant architects design a colony to cut the risk of disease. Humans, take note!

Ants are many things. They’re hard workers and intensely social. They’re quite strong for their size. And now they may also be a source of architectural inspiration too — for designing spaces that reduce the spread of disease.

This discovery comes from a new study focused on Metarhizium brunneum, a common and lethal fungus for insects, including the black garden ant. For this fungus to propagate, it kills its host, taking over the host ant’s dead body and transforming it into something called a sporulating cadaver.

“It’s basically completely covered in spores and is highly infectious,” says Nathalie Stroeymeyt, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Bristol.

In research in the journal Science, she and her colleagues report that black garden ants manipulate the structure of their nests to respond to this fungal pathogen and slow down its transmission.

Social distancing, ant-style

In 2018, Stroeymeyt and her colleagues published a study that considered how small colonies of black garden ants respond socially to the introduction of the lethal fungus. The scientists glued tiny squares of paper with QR-like codes to the thoraxes of the ants and used an automated video tracking system to follow the movements of individuals over time.

The infected workers quickly self-isolated. “They spend more time out of the colony to prevent contamination of their nestmates,” she says.

In addition, some of the healthy ants — the nurses that take care of the queen, eggs and larvae — increased their distance from the foragers, “which are the ones who go outside and are more at risk of contracting a disease,” says Stroeymeyt. “So it was a form of proactive social distancing, if you wish.”

This work revealed that the ants altered their social behavior to protect themselves from infection and safeguard high-value members of the colony.

Stroeymeyt wondered if the ants were making bigger changes — by altering the spaces they shared — the “hundreds of chambers connected by thousands of tunnels,” as she puts it.

So Stroeymeyt teamed up with Luke Leckie, now a systems biologist at Indiana University Bloomington, to investigate whether the ants could shift how they excavated and built their nests when threatened by a pathogen.

Leckie says ants are industrious and dynamic builders.

So that made him wonder: “Maybe they can manipulate the structure of their nest to avoid these transmission hotspots where there can be loads of interactions and protect the colony from the spread of epidemics.”

Architectural immunity

To determine the impact of infection on nest architecture, Leckie and his colleagues gave small colonies of black garden ants a day to start building their nests. Then, in half of the nests, they introduced individual ants infected with the fungus.

Over the course of six days, he took noninvasive CT scans of the nests. “They let us see the three-dimensional structure of the nests as it’s developing over time,” Leckie says.

There were clear differences between the nests that were exposed to the pathogen and those that were not. According to computer simulations, these differences appeared to help lower disease transmission, reducing the risk of the fungal pathogen breaching the entire nest.

First, the nests were more compartmentalized and less interconnected. Nest entrances were also spaced farther apart, reducing interactions between ants that were entering and exiting. Travel routes were longer, which made the nests less efficient but helped insulate healthy ants from infected ones.

These structural changes had the overall effect of improving the ability of infected ants to isolate themselves, which Stroeymeyt had documented previously.

The social and architectural changes “work together to really provide a very effective protection,” she says. “It’s a first demonstration of a social species outside of humans who actively modifies the spatial structure of the environment in face of a threat. That I find absolutely fascinating.”

Sarah Kocher, an evolutionary biologist at Princeton University who wasn’t involved in the study, says the findings deepen our understanding of something called social immunity found among many types of ants and bees.

“Instead of relying on their individual immune systems,” she says, “they work together as a group to try to minimize disease spread and utilize ways that their collective behaviors can help to defend them against these diseases.”

In addition, Kocher believes these ants have something to teach us. “Some of the principles could easily be applied to the way that we are designing public spaces that could help us prevent disease spread as well,” she says.

For instance, the ants seem to be protecting more vulnerable members of their community by isolating sections of their enclosure.

Stroeymeyt agrees that we can seek inspiration from these ants, developing human ways of using architecture to reduce the risk of infection. “We can learn from social insects, which have evolved over millions of years,” she says, “to find strategies that balance this protection against epidemic without completely disrupting the functioning of the entire colony.”

But she believes these connections will emerge down the road since the results in this paper are “too ant-like to have direct application today.”

So perhaps one day, humans will benefit from this notion of architectural immunity, inspired not by antibodies — but by ant bodies.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Ants are many things. Like, they’re very strong for their size, and they’re intensely social. And, as Ari Daniel reports, they might be sources of architectural inspiration, too, for designing spaces that reduce the spread of disease.

ARI DANIEL, BYLINE: The ant in question is Lasius niger, the black garden ant.

NATHALIE STROEYMEYT: It lives everywhere in Europe, and you can just collect queens during the mating flight in July, which makes it very easy to work with.

DANIEL: This is Nathalie Stroeymeyt, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Bristol who studies how these ants deal with a deadly fungus.

STROEYMEYT: In order to successfully transfer, it needs to kill its host.

DANIEL: Transforming that host ant into something called a sporulating cadaver.

STROEYMEYT: It’s basically completely covered in spores, and it’s highly infectious.

DANIEL: Which puts any ants nearby in grave danger. Stroeymeyt has studied how these ants respond socially to the lethal fungus by gluing tiny squares of paper with QR-like codes to their thoraxes to track the individual ants’ movements over time. First, she saw that infected workers quickly self-isolate.

STROEYMEYT: They spend more time out of the colony to prevent contamination of their nest mates.

DANIEL: In addition, some of the healthy ants, the nurses that care for the queen, eggs and larvae, increase their distance from the foragers.

STROEYMEYT: Which are the ones who go outside and are more at risk of contracting a disease – this was a form of proactive social distancing, if you wish.

DANIEL: Combined, this work revealed the ants alter their social behavior to protect themselves from an epidemic and safeguard high-value members of the colony.

STROEYMEYT: And that happens even when the nest is as simple as it can be with a single chamber. But in reality, they occupy these nests made of hundreds of chambers connected by thousands of tunnels.

DANIEL: Stroeymeyt wondered whether the ants also shift how they build and excavate their nests when threatened by a pathogen. She teamed up with Luke Leckie, now a systems biologist at Indiana University, to investigate. He gave small colonies a day to start building their nests before introducing ants infected with the fungus.

LUKE LECKIE: We were taking CT scans of the nests. They let us see the three-dimensional structure of the nest as it’s developing over time.

DANIEL: Within six days, there were clear differences between the nests exposed to the pathogen compared to those that were not – differences that, according to computer simulations, appeared to help slow down disease transmission.

LECKIE: They were kind of more compartmentalized, and they were less interconnected.

DANIEL: Nest entrances were also spaced farther apart. Travel routes were longer, making the nests less efficient. But these structural changes enhanced the previously documented social response of the ants to isolate. Here’s Nathalie Stroeymeyt again.

STROEYMEYT: It’s the first demonstration of social species outside of humans who actively modifies the spatial structure of the environment in face of a threat. That, I find, is absolutely fascinating.

DANIEL: The results are published in the journal Science. Sarah Kocher is an evolutionary biologist at Princeton University who wasn’t involved in the study. She says the findings deepen our understanding of something called social immunity found among many types of ants and bees.

SARAH KOCHER: Instead of relying on their individual immune systems, they work together as a group to try to minimize disease spread.

DANIEL: In addition, Kocher believes these ants have something to teach us.

KOCHER: Some of the principles could easily be applied to the way that we’re designing public spaces that could help us prevent disease spread as well.

DANIEL: Principles like protecting more vulnerable members of the community and isolating sections of an enclosure. Think of it as architectural immunity delivered not by antibodies, but by ant bodies. For NPR News, I’m Ari Daniel.

(SOUNDBITE OF JONUFF’S “CROW”)

As Mississippi waits to spend opioid settlement funds, children and families suffer

Mississippi will receive more than $400M to fight the opioid epidemic. So far, officials haven't directed it toward programs that support addiction recovery.

Alabama’s new state climatologist takes the reins

The controversial John Christy is retiring as Alabama’s state climatologist. Lee Ellenburg now assumes the role and is already making a few changes, including declaring that climate change is real and caused by humans.

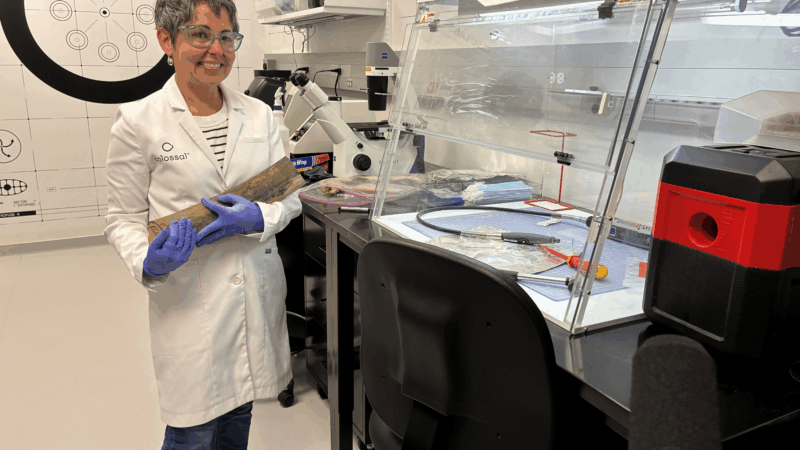

Colossal Biosciences breeds controversy while trying to revive mammoths

A Texas biotech company is trying to bring mammoths and other extinct creatures back to life. The science is as intriguing as the ethical questions are thorny.

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

Why are we captivated by the spaces where where authors write? Katie da Cunha Lewin set out to explore "The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love."

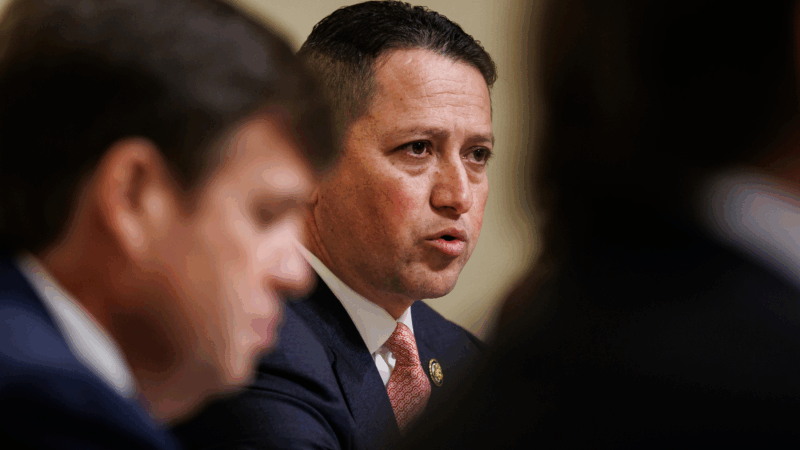

GOP Rep. Tony Gonzales heads to a runoff in Texas amid a new ethics probe in the House

Texas Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales has faced increasing pressure from his party to resign or drop out of his race after allegations of an affair with a staffer.

Satellite images show Iran school strike hit more targets than earlier reported

The images suggest that precision munitions struck other buildings, including a clinic that was also inside the complex.